The men watched as the landscape shifted, dissolving and disappearing in front of their eyes. “Poojok.” Mist. Only yesterday the scientists were elated upon seeing hills and snow-capped peaks appear on the horizon, sure they had found Crocker Land, a landmass observed and named eight years previously by the famous explorer Robert E. Peary. Their two Inuit guides, however, were less sure. When they emerged from the igloo the next morning, there could be no doubt. The sky had shifted, the mirage had lifted, and they gazed upon an empty expanse of Arctic sky.

There was no Crocker Land to be found.

The Crocker Land expedition was a brilliant illustration of Murphy’s Law. If something could go wrong, it likely did. Led by explorer and anthropologist Donald B. MacMillan, the trip suffered from ships run aground, outbreaks of mumps and influenza, blizzards and frostbite, failed radio communications, land that disappeared in a mist, and, most disturbingly, a murder.

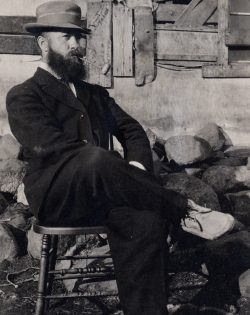

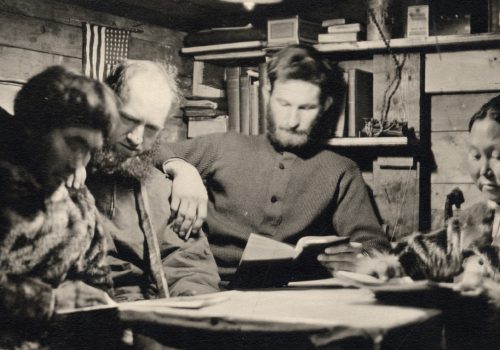

In total, seven Americans traveled to the western coast of Greenland in 1913, including scientists and Illinois graduates W. Elmer Ekblaw and Maurice Tanquary. In addition to searching for Crocker Land, the men planned to traverse the polar ice cap and conduct research in a wide variety of areas, including geology, ethnology, botany, and zoology.

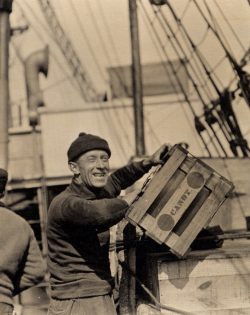

Given their luck, it should be no surprise that what had been planned as a two-year trip extended into four when multiple rescue ships became stranded in polar ice, unable to reach the team. Slowly the Americans began to return, some traveling as much as 1,000 miles by dog sled to reach boats on open water. By the time all the Americans had returned in 1917, the world was embroiled in war, the government started taxing our incomes, and some new kid named Babe Ruth signed with the Boston Red Sox.

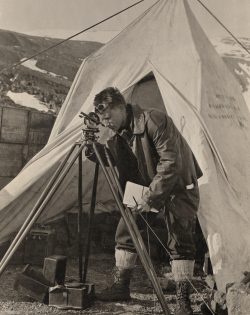

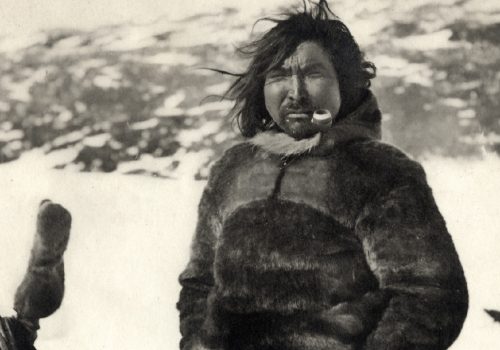

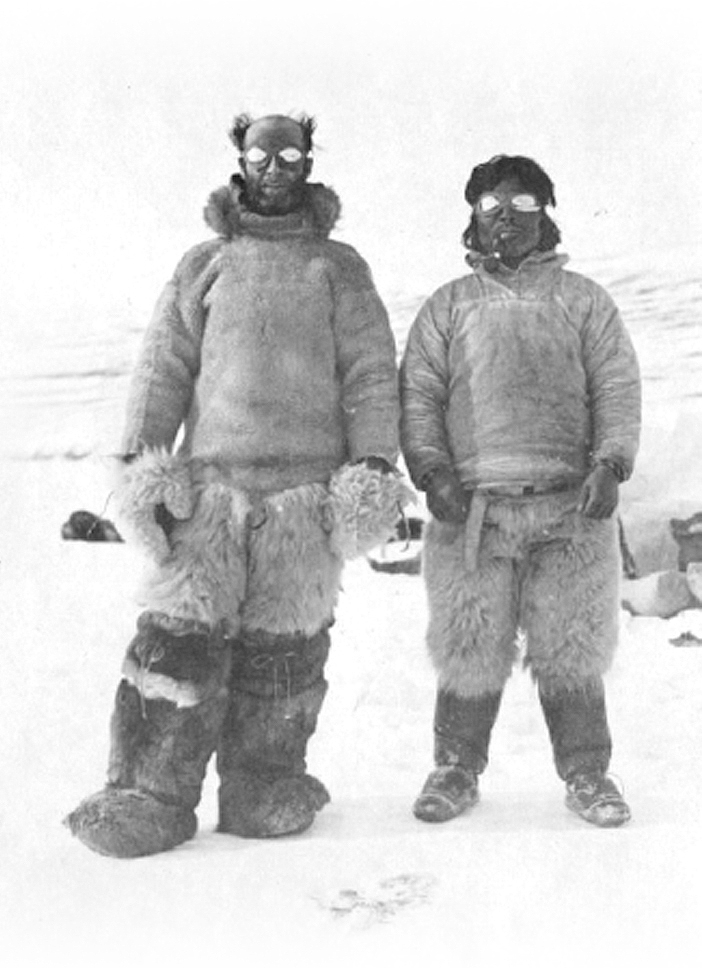

Many of the explorers published accounts of the trip upon their return. MacMillan took thousands of photographs as well. These stories and photos capture the complexity of Arctic life and of exploration, but also reveal uncomfortable realities about exploration and race. The Spurlock Museum at Illinois is home to a large collection of artifacts from this expedition, including copies of 4,500 of the expedition’s images. A recent exhibition put together by museum staff considered those issues; a modern museum’s look at a complicated part of our history.

All photographs are reproduced courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, New York City, unless otherwise noted.

The Explorers

Searching for Crocker Land

The search for Peary’s Crocker Land was only one of the expedition’s objectives, but it proved to be the most dramatic. After a long winter in camp and much preparation, various teams of men left Etah in February 1914 to bring supplies to checkpoints along the route to Crocker Land. By the time MacMillan and his team left (on the less-than-auspicious date of Friday, February 13) nineteen men, fifteen sleds, and 165 dogs had preceded them.

This trip, however, was plagued by trouble. By the time MacMillan caught up with the full party, men were sick with influenza and mumps. Disheartened by cold, some were what MacMillan deemed “chicken-hearted.” The party hastily returned to Etah.

A second journey was comprised of a much smaller group. MacMillan left camp on March 10 joined by Ekblaw, Green, and four Inuit guides. The men fared much better on this excursion, but by mid-April they found the hunting insufficient. MacMillan decided to send two men back, saving on provisions for the rest of the trip.

That left just four men at the edge of the earth. Only three would return.

✦ ✦ ✦

‘He lay face downward, unmoving, in the snow.”

After traveling nearly 750 miles by dog sled, enduring sub-zero temperatures and extreme hunger, the four men arrived at Cape Thomas Hubbard on April 28, standing in the same spot Peary had in 1906. MacMillan and Green were joined by Piugaattoq and Ittukusuk, skilled Inuit sledders and hunters who had worked on previous American Arctic expeditions.

At first, they too were convinced they saw land. MacMillan wrote, “Yes, there it was! It could even be seen without a glass…we would have staked our lives upon its reality.”

But, in fact, as the day unfolded the men watched as the landscape shifted, dissolving and disappearing in front of their eyes.

On that fated April day, when the mist cleared and Crocker Land was revealed to be a mirage, MacMillan decided to split the four men into two teams, sending Green and Piugaattoq to explore the shores of the southwest coast while he and Ittukusuk headed east. Hoping to make the most of the trip by mapping the land, they planned to meet up in a few days to complete the trip back to Etah.

Green’s childhood dreams of Arctic discovery didn’t quite come to fruition. Piugaattoq expressed his worry at the lack of food and the exhaustion that plagued both them and their dogs. He was also worried about the risks MacMillan and Green were taking by crossing areas of thin ice. As they descended down the coast, the two men were abruptly caught in a blizzard. “For two days we half suffocated, making one igloo above the other as the drift buried us,” Green wrote. When the storm cleared, Piugaatooq seemed to have had enough and turned his sled toward Etah, taking with him the only cooking stove and oil they had. Green ran over snow and ice on blistered feet to stop him, but only the shot from Green’s rifle stopped Piugaattoq from continuing.

✦ ✦ ✦

Getting away with murder

At the rendezvous point, MacMillan had begun to worry about Green and Piugaattoq. He had given the men three days of food, but six days had now passed. On the afternoon of May 4, eight weeks after the men had originally left Etah to find Crocker Land, Green appeared on the horizon, alone.

Days earlier—shortly after the shooting and following a haunting night with the dead man staring at him in an igloo—Green left Piugaattoq’s body behind an iceberg. Upon his reunion with MacMillan and Ittukusuk, he wrote, “No attempt was made to describe the truth of Peewahtoq’s disappearance, and probably the younger man [Ittukusuk] concluded that the sooner out of this scrape the better.”

Both Green and MacMillan write about Piugaattoq’s murder in their memoirs. MacMillan blames the event on Green’s “inexperience in the handling of Eskimos, and failing to understand their motives and temperament, [he] had felt it necessary to shoot his companion.”

Green, on the other hand, admits to succumbing to the pressures of the Arctic, to experiencing a break in reality sparked by the fear of losing his food and dogs. “I wish to rather illustrate how little removed we are from the creatures we despise,” he wrote. “Grip a man’s heart and his reactions are inarticulate protests against the unseen force which throttles him.”

Both write about Piugaattoq’s death in a striking, matter-of-fact manner. MacMillan devotes less than a page; more space is taken up by detailed descriptions of hunting. Green devotes more time to the incident, but in the end his account seems an opportunity to wax poetic about his mental state and spin yarns about his bravery in the face of attacking dogs and blistering cold.

Of course, only one man survived the standoff in the snow. To our knowledge there is no surviving account of the events or their aftermath from the Inuit perspective.

And Green was never charged with Piugaattoq’s murder.

✦ ✦ ✦

A modern museum and narratives of exploration

by Beth Watkins, Education and Publications Coordinator, Spurlock Museum

A century after the Crocker Land expedition, the photographs and objects the members collected offer a subjective picture of how the expeditionary crew imagined themselves and the world around them. By claiming that this picture was objective, narratives of exploration generally tried to present the world as a controlled, stable place. But failures, accidents, and mistakes shaped these accounts just as much as carefully laid plans.

From the Spurlock Collection

The Spurlock staff wanted our exhibit about the expedition to demonstrate just how messy, chaotic, and troubled such undertakings really are. Noelle Belanger, doctoral student in Art History, and Anna Stenport, Professor of Scandinavian Studies, were key collaborators in this project. These scholars introduced us to the complicated context of histories of the Arctic, including exploration and scientific travel, and how they have shaped contemporary issues of voice and representation. Belanger also wrote exhibit text and selected images for display that illustrate the problems of photographs as documents: who has the authorial power of the camera, what do those people choose to show, and what do they omit. “By accepting the impossibility of knowing anything with confidence,” she wrote, “we can recognize these photographs for what they are: the products of the imagination and vision of a group of men who were searching for an unknown, and eventually unreal, place.”

A 1913 document from the American Museum of Natural History (the primary organizer of the expedition) illustrates some of the tensions in scientific attitudes of the time.

The [northwest Greenland] tribe is dwindling. Contact with the whites has already seriously affected their life and customs, but they are still singing their weird native songs and reciting the traditions of their people. It is highly important to preserve these by means of phonographic records for future study and comparison.

Euro-Americans were aware of at least some of the detrimental effects of their increasingly global intrusion into native lifeways and lands, but anthropological work and the enhancement of knowledge, produced and consumed by white populations, were valued over any risk of negative impact on the subjects. The objects the team collected and the images they created represent the perspective of the white American outsiders, both through what they include and through what they don’t. The Crocker Land expedition is a descendant of the attitudes of people like Robert Peary, who on his many trips to find the North Pole actually took away human beings from the Arctic, both living ones and illicitly stolen burial remains.

Life in Etah

The more research we did on the Crocker Land expedition, the more questions we had to ask about the expedition and about the artifacts and photos that resulted from it. We started our artifact research with “What is this item?” and progressed to “Why don’t we know what it is?” and “What meaning does it have, completely removed from its context and housed in a museum thousands of miles from where it was made and used?” Interrogation became increasingly important. What should we do with collections that result from the scientific imperialism of previous centuries? It is very much the responsibility of museums in the 21st century, especially those of us who are part of universities and with the opportunity to collaborate closely with scholars, to look critically at our collections and the histories they embody.

The Spurlock Museum of World Cultures is a regional center for cultural and archaeological collections from throughout history and across the globe. To support their work, please visit their website.