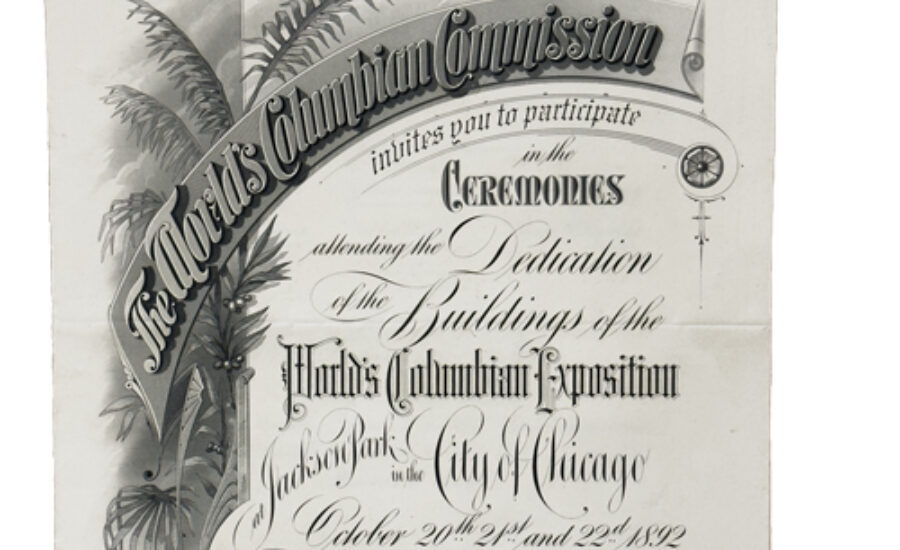

The 1893 World’s Fair evokes images of the Ferris wheel spinning, the sun reflecting off Lake Michigan onto the buildings of the “White City,” and top hats and parasols parading down the midway.

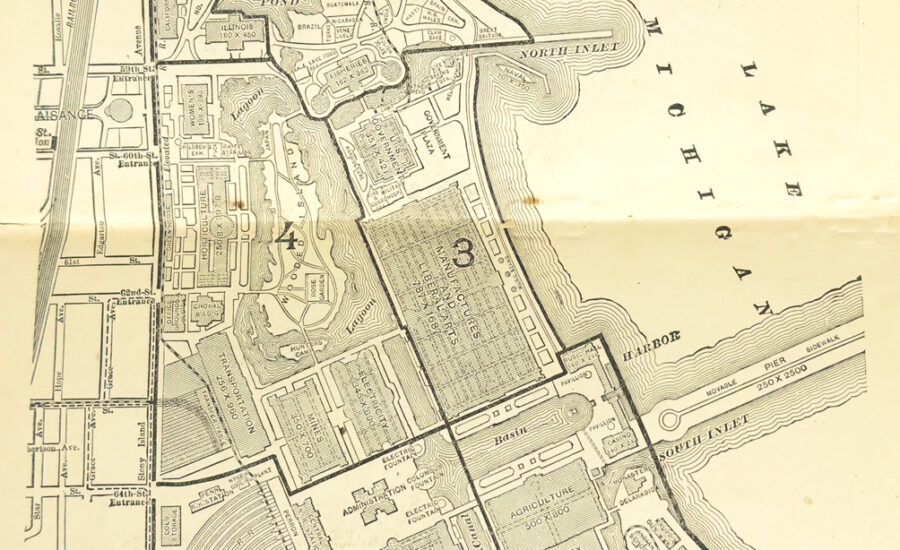

The occasion was a display of the ultimate grandeur, filled with nations sharing their cultures and the newest inventions to amaze visitors. From May through October, more than 27 million people visited the fair, giving Illinois the opportunity to show the world what our young campus had to offer. After all, the university had been in existence for only twenty-five years. According to Winton Solberg, a renowned historian of the university, it took our faculty two and a half years to prepare our exhibit, “which consisted of nine freight carloads of material that stressed engineering and science and occupied eight thousand square feet in the Illinois State Building.”

The university’s exhibit was the most comprehensive educational exhibit at the fair, each item selected to showcase the work of the colleges and departments at the university. These items ranged from grains harvested from fields, skeletons of farm animals, engine designs and drawings, mounted mammals and birds, and even student exams.

The fair lives on at the University of Illinois, preserved in the folders, boxes, and closets of the University Archives and libraries. These items were collected by the fairgoers, passed on by their family members, and, in some cases, donated by philanthropic alumni so we can imagine what our great state offered to the world over one hundred years ago.

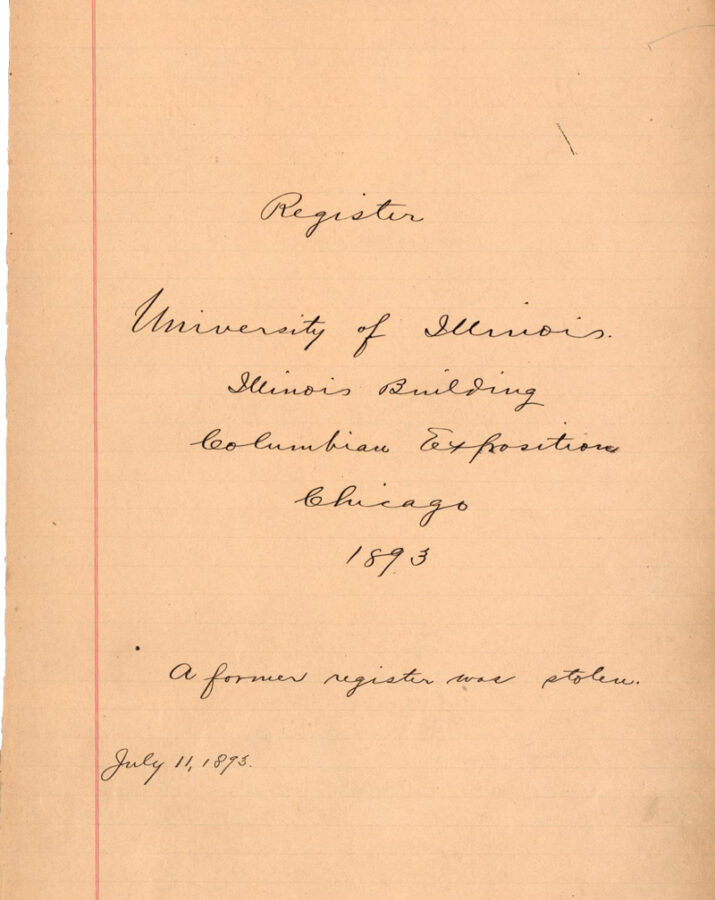

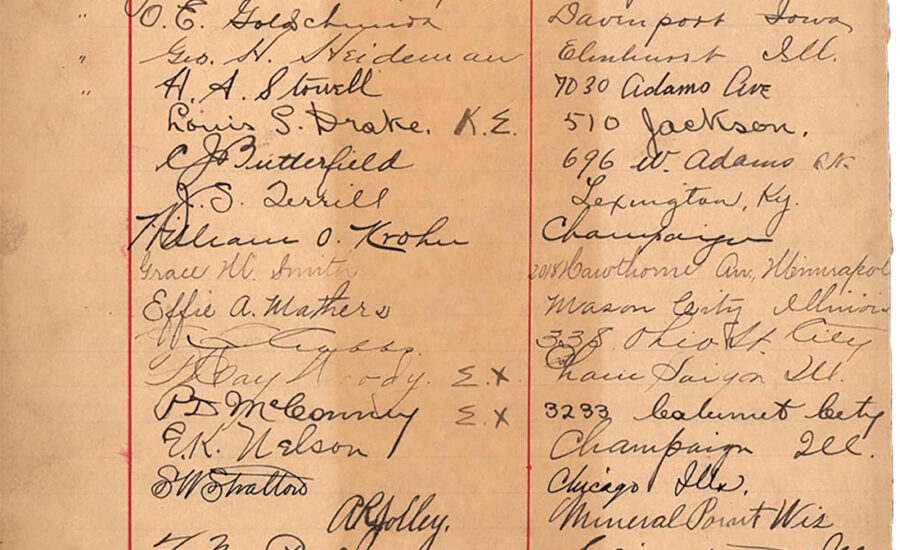

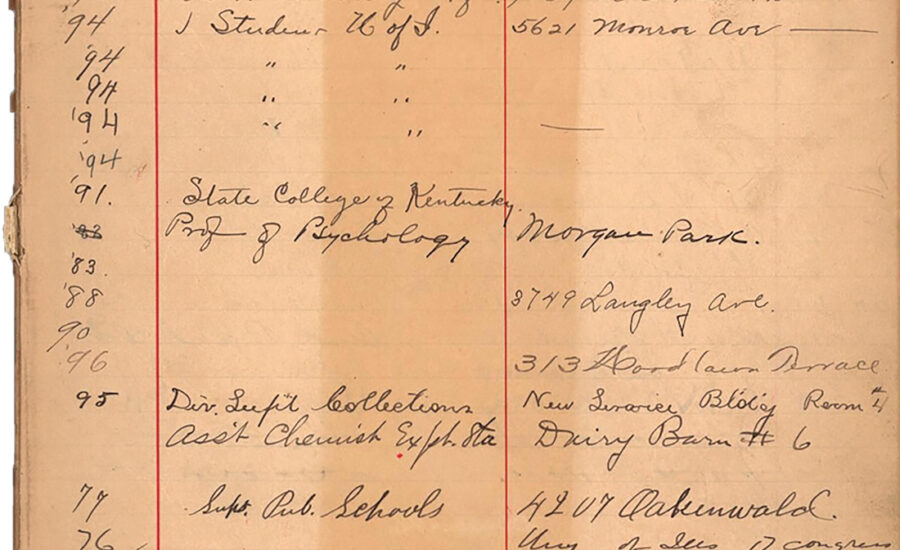

University of Illinois Guest Register

Hundreds of names appear in the brittle bindings of this record book. The perfect script eternally commemorates the University of Illinois alumni and students who visited the fair in July 1893. People visited from around the country—now veterinarians, teachers, librarians and more. They signed the register and marveled at the exhibit their school was showing to the world.

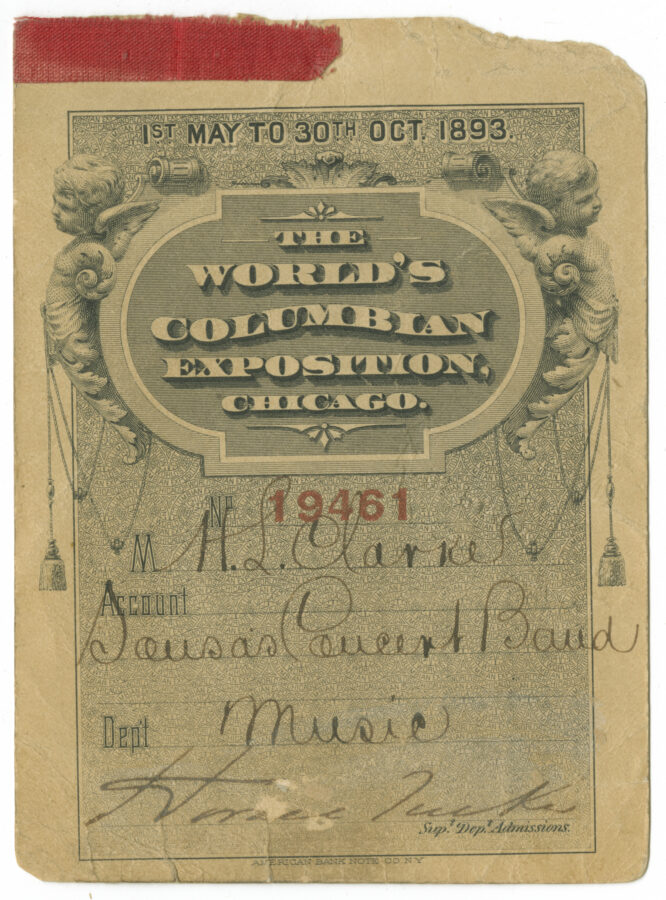

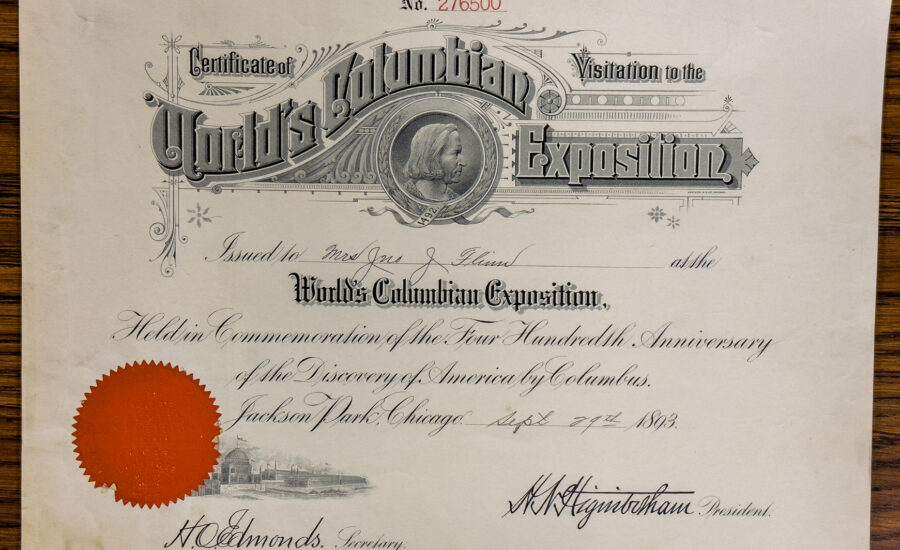

Herbert L. Clarke Fair Pass

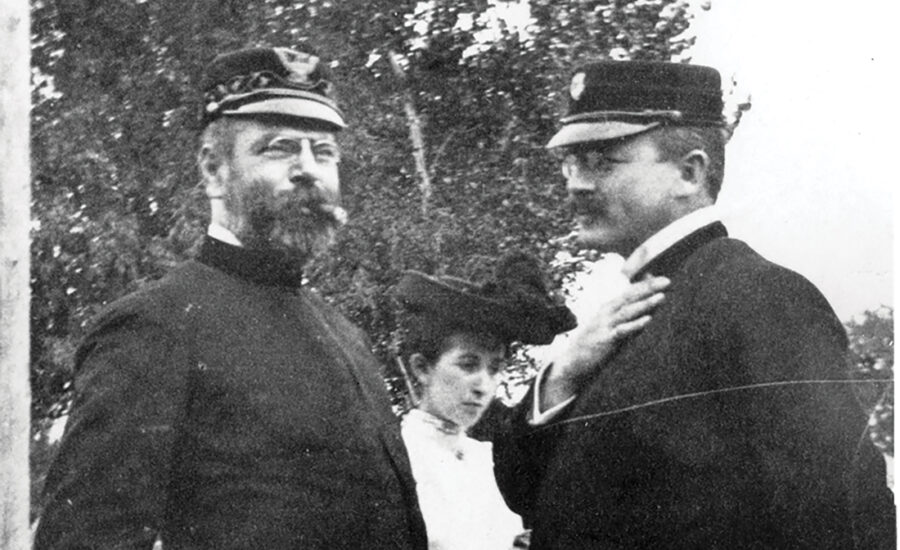

Thirty-eight days—that’s how long John Philip Sousa’s band played at the World’s Fair in 1893. They were the official band of the fair, an honor which catapulted their success in the coming months and years. The increasingly successful band would not have been complete, however, without the premier cornetist of the time, Herbert L. Clarke.

On the fair’s opening day, the Sousa band filed into Mechanic’s Hall and played an original composition, “Salute of the Nations to the Columbian Exposition.” Throughout the fair, the Sousa band played alongside the melodic voices of the Ladies’ Orchestra and Chorus Band. In fact, during their last performance at the fair, Clarke was notably featured to bring it home.

Clarke grew up in a musical family with a father who performed as a musician and two brothers who went on to showcase their musical talents by playing professionally. Clarke got the itch for making music his career when playing in a local restaurant and making his first few dollars doing what he enjoyed. After multiple moves with his family and picking up various performance jobs, he found his break with the Citizen’s Band of Toronto. He went on to play with Patrick Gilmore’s band before landing with the Sousa Band as solo cornetist just in time for the Fair.

Clarke went on to serve as the assistant director, composer, and arranger of the Sousa band, played in the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, as well as conducted the Long Beach Municipal Band.

Sousa had a close relationship with University of Illinois band director A. A. Harding—Sousa composed the “University of Illinois March,” and many of our graduates joined Sousa’s band. Upon Sousa’s death, the University of Illinois Band Department received boxes, trunks, and papers from his estate to create the Sousa Archives, where Clarke’s World’s Fair pass resides.

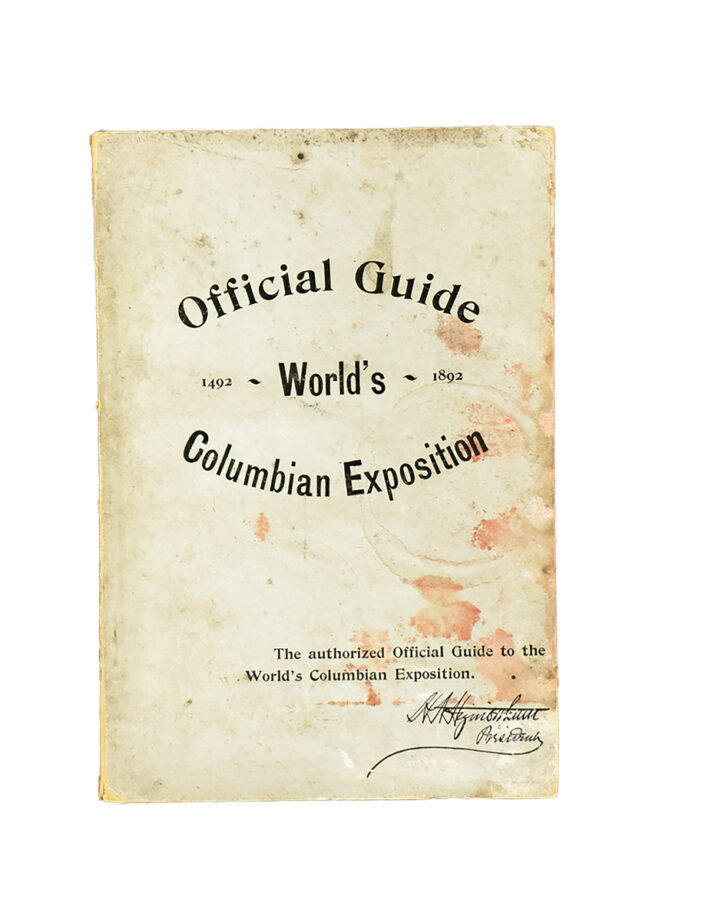

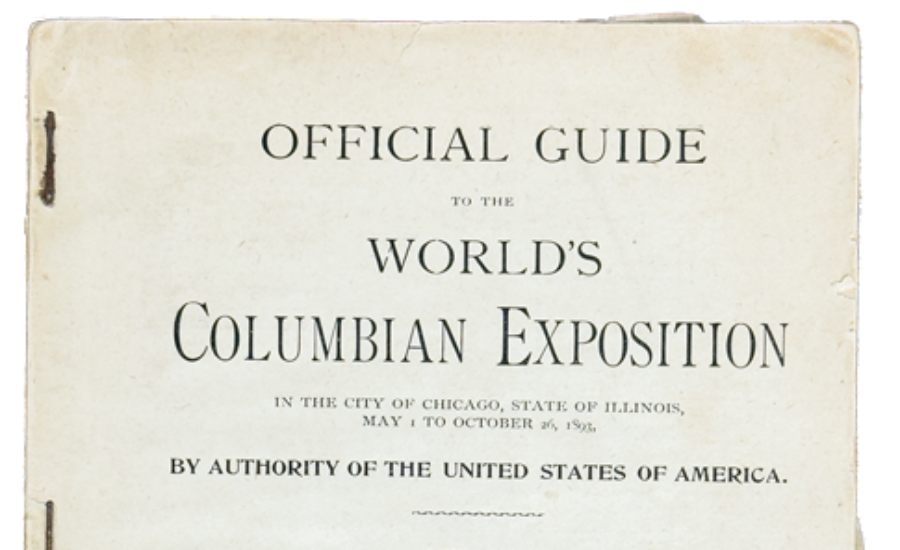

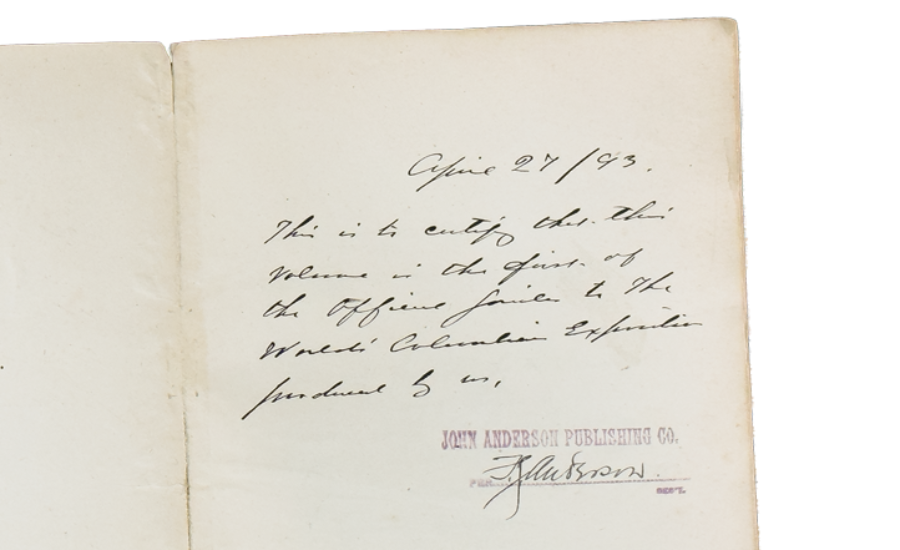

Flinn Fair Guide

Immigrating from Ireland as a young boy, John J. Flinn grew up in Boston. Starting a newspaper career that took him from Boston to St. Louis and later Chicago, he eventually became the editor of the Chicago Times. Flinn’s time in Chicago happened to overlap with the 1893 World’s Fair, and he was asked to author the official guide to the fair.

A significant version of this guide lives on within the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections. The inscription on the inside cover reads, “This is to certify that this volume is the first of the Official Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition” and is signed by the publisher, John Anderson. A complete digitization of the guide can be found on the Library of Congress website. The Flinn collection was donated to the university in 1995 by Flinn’s grandson, a graduate of the University of Illinois.

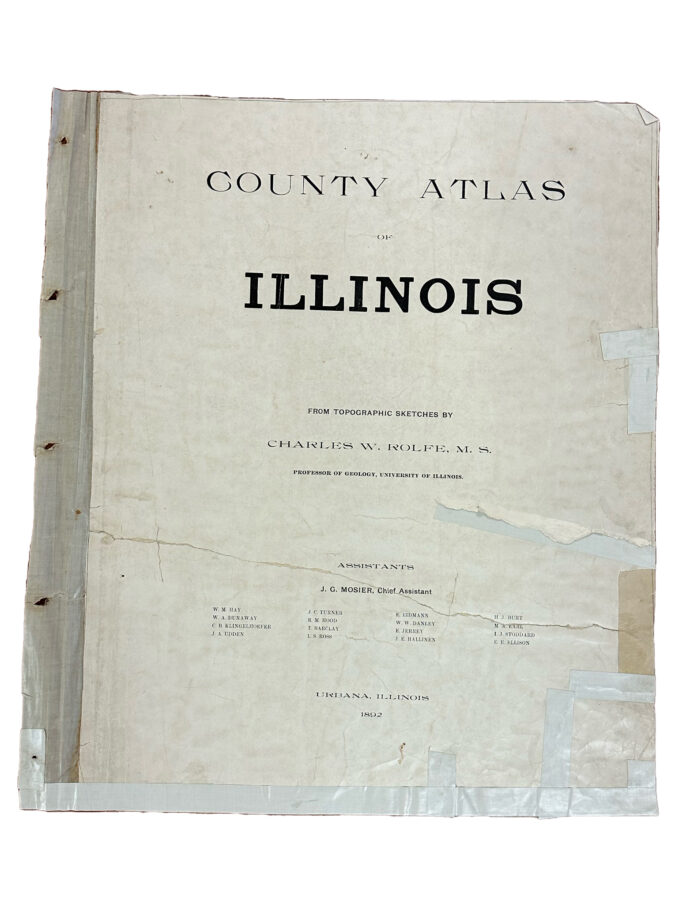

Rolfe Topographic Map Drawings

An oversized file sits on the table at the University Archives. Upon opening the folder, a bold ILLINOIS appears printed on fragile paper kept intact with yellowing tape. As you turn the pages, you hear the crinkle of the one hundred thirty-year-old paper while the impeccably written script and detailed drawings of Professor Charles Rolfe and his students materialize and showcase the topography of Illinois.

The County Atlas of Illinois was created by Professor Charles Rolfe and seventeen university students for the World’s Fair and “was one of the earliest to topographically map the entire state.” Featured in the university exhibit in the Illinois Building, the atlas gave visitors a scientific peek into the Illinois landscape and into the skills students were learning on campus. Using data from the Mississippi River Commission, the Lake Survey, and Geologic Survey, the students painstakingly drew each rise and fall of Illinois’s landscape.

Rolfe was a graduate of the first class at the University of Illinois in 1872. As a professor, he had his hand in many of the subjects taught at the university including mathematics, natural history, botany, and horticulture. He eventually became head of the geology department.

Rolfe’s daughter, Mary, reminisces about her father’s teaching career in a 1960 archival interview, where she explains that when given the chance to focus solely on geology, he still kept an academic toe in physiology. “Father had his choice when they decided to separate [the subjects] and he chose to be part of geology. . .But as long as he lived, he had his medical books and physiology books and that’s what he did for recreation.”

University President Draper added another title to Rolfe’s curriculum vitae—”squirrel master”—when he asked Rolfe to “domesticate campus squirrels after the Trustees authorized a project to do so.”

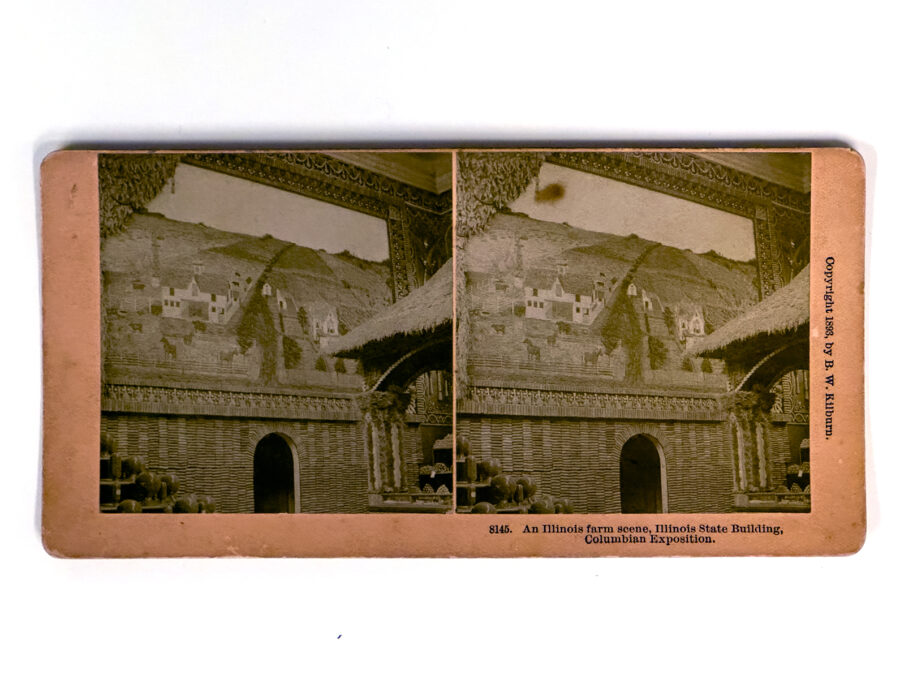

Stereographs

Two seemingly identical faded images are mounted to a thick tan card tucked in a folder in the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections. When put behind a stereoscope, the two images fuse into one three-dimensional experience of a farm scene in the Illinois Building, the largest state building at the fair.

Some describe stereographs as the first rendition of virtual reality. Playing on the anatomy of the human eye, the stereograph is constructed of one image taken or drawn from different perspectives. The stereoscope functioned like a modern VR headset, transporting viewers in the mid-1800s into the worlds of the images they viewed. This stereograph card walked viewers inside the doors of the Illinois State Building at the fair.

While the image portrays the detail of a farm scene, the 92,388 square foot building was packed to the brim to celebrate the magnificence of the host state. Life in Illinois was depicted through exhibits on agriculture, grain and forestry, horticulture, clay, and the great educational institutions of the state.