Our campus is home to what now numbers in the millions of collected, created, donated, and unearthed objects from all over the world that are part of the university’s permanent collection. These treasures have been amassed through the hard work and generous philanthropy of countless students, researchers, professors, alumni, and friends.

This occasional series uncovers and discovers the fascinating stories behind these curiosities—from items that reflect our natural and cultural history to art collections that represent all eras and mediums to the endless bounty of riches found in our library alone, including rare manuscripts, maps, and books.

These materials (displayed in museums and glass cabinets, tucked safely in boxes and drawers) are used by researchers as well as by instructors in classrooms and they do nothing less than tell the story of our collective humanity.

In this installment of Curiosities, we explored the riches of the Map Library which is home to over 630,000 maps, atlases, and photographs. Map Librarian Jenny Marie Johnson and her team answer questions and provide access to pieces in the collection for researchers around the world. “Every map has a point of view,” she said. “When I buy maps I’m looking for a piece with a point of view, a story, maybe an interesting graphic technique or something that shows a different perspective or something we didn’t know.” From illustrating fictional lands to helping you find your way home, these colorful way finders tell us as much about where we are as who we are.

“They Open A Door And Enter A World”

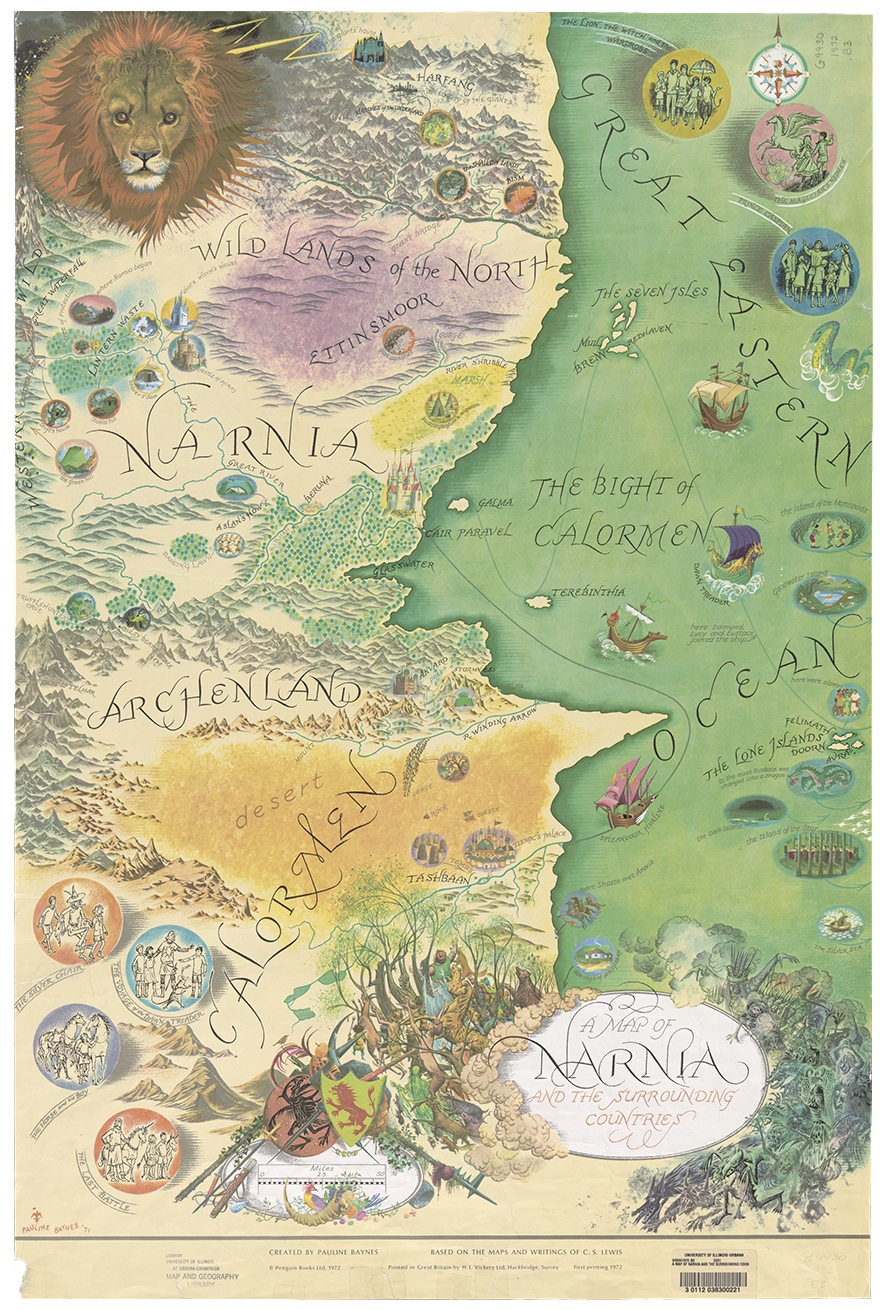

Pauline Baynes was born in England and spent her childhood in India, where her father was a commissioner with the Indian Civil Service. Those happy years for Baynes would end when her mother decided to send the children back to a boarding school in England. It was a move that played a significant role in Baynes’ life.

A biographical sketch of Baynes from her website explains that “For the rest of her life she was haunted by memories of the misery of being abruptly parted from her Indian ayah (and from the family’s pet monkey, who was trained to take tiffin at the tea table), and of crying herself to sleep on the voyage home.”

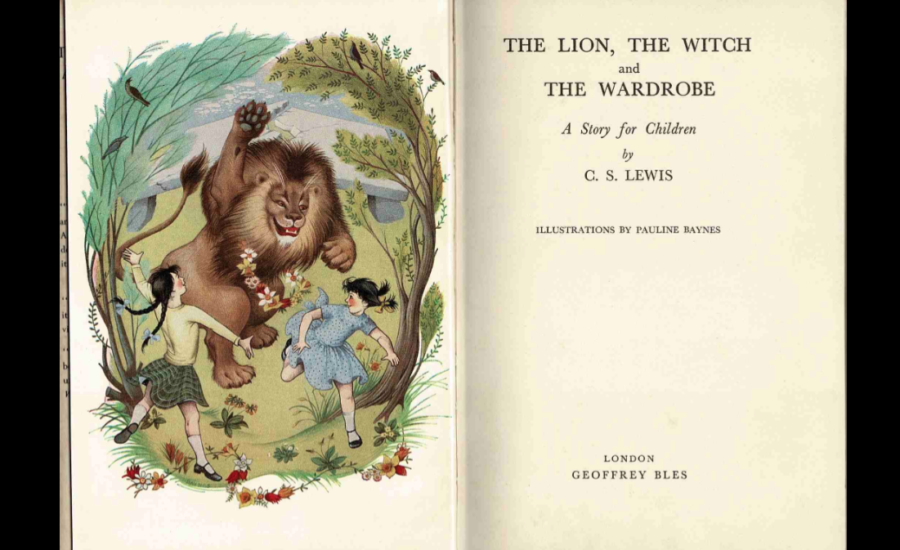

She found solace in her art, which she ultimately turned into a successful career. After the Second World War, her book illustrations captured the attention of J.R.R. Tolkien who commissioned her to illustrate several his books including Farmer Giles of Ham and Bilbo’s Last Song. But it was her collaboration with author C.S. Lewis, whom she met through Tolkien, that would result in her most iconic work.

Baynes illustrated all seven of Lewis’ Narnia books, both for their original publications in the 1950s as well as subsequent reprints. For many years, the internal illustrations were rendered in black and white, but decades after their publication, she painted them with watercolor, exemplified in this gorgeous map of the fabled land.

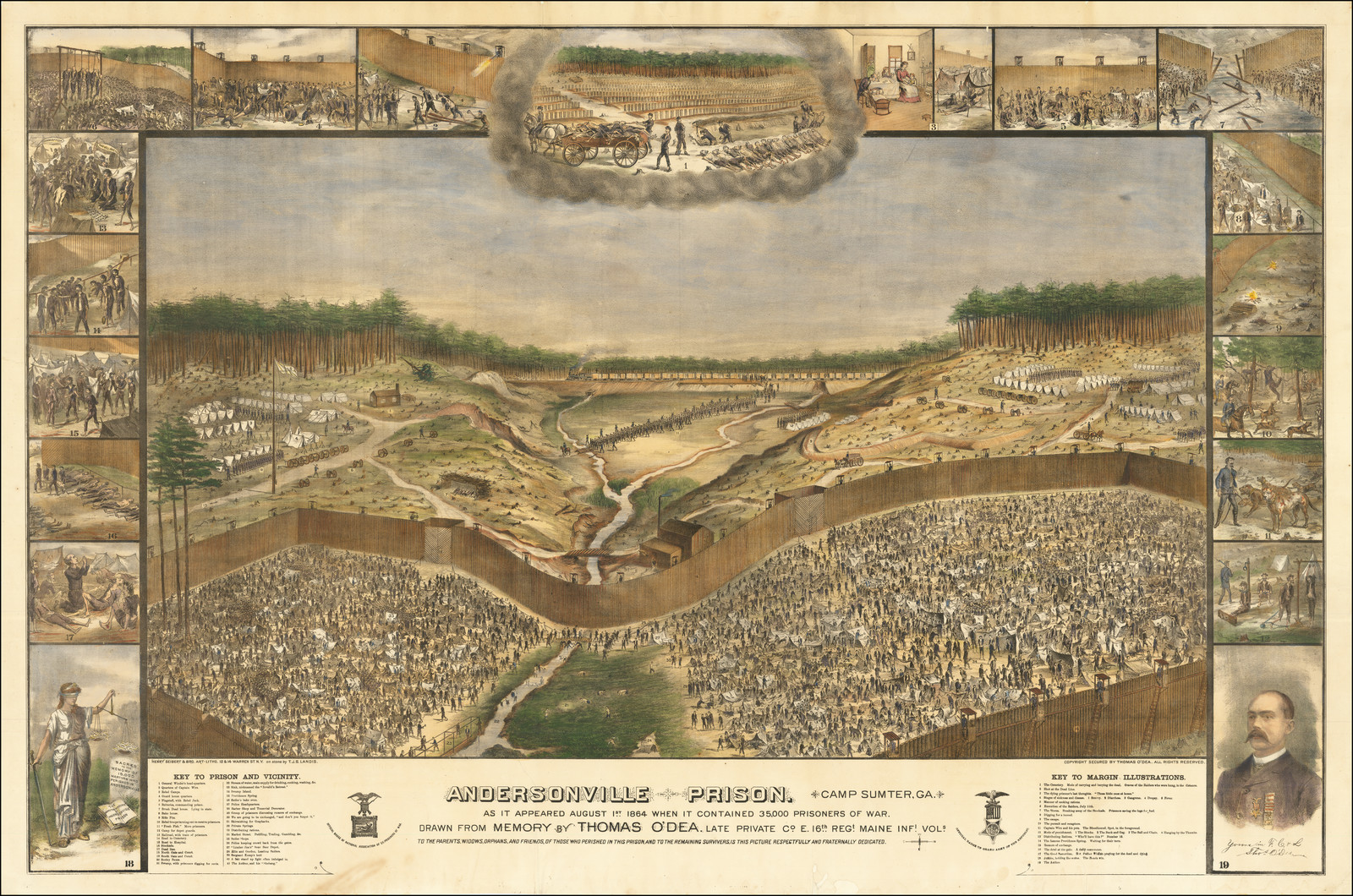

A Prisoner’s Perspective

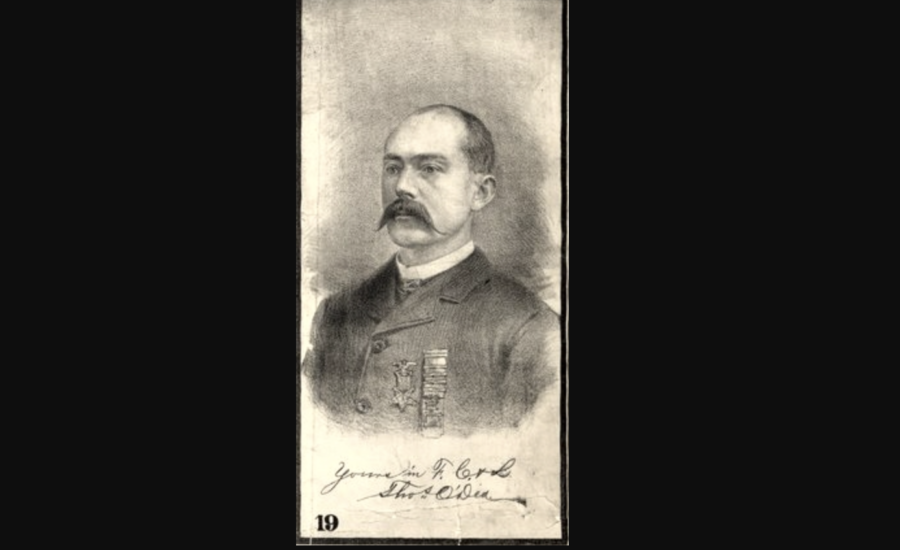

Thomas O’Dea was interned at the infamous Andersonville Prison for less than a year (summer 1864-February 1865) but those months had a lifelong effect. When he arrived at Andersonville, the prison camp, which had been operating for half a year, was already at more than three times its intended capacity. There were 35,000 men in a space designed to house 10,000. O’Dea, like many other prisoners, was ill when he was released. Additionally, his family, which had been in Boston, had completely disappeared.

O’Dea originally created his Andersonville Prison as a pencil sketch in reaction to a photograph he saw in 1879 which appeared to imply that the camp had been clean, orderly, and well-maintained; the view took six years to complete. The central image and surrounding nineteen sketches show all aspects of the camp’s appalling conditions, from the prisoner’s arrival to their deaths. O’Dea included himself in the central scene and in a portrait in the margin. In 1887, O’Dea wrote a pamphlet titled, History of O’Dea’s Famous Picture of Andersonville Prison explaining elements of the image. The bird’s eye view image is roughly oriented with west at the top of the sheet. Originally printed in black and white, the copy in the Map Library is expertly hand colored. Acquired with the assistance a Library Friend.

Mapping the War

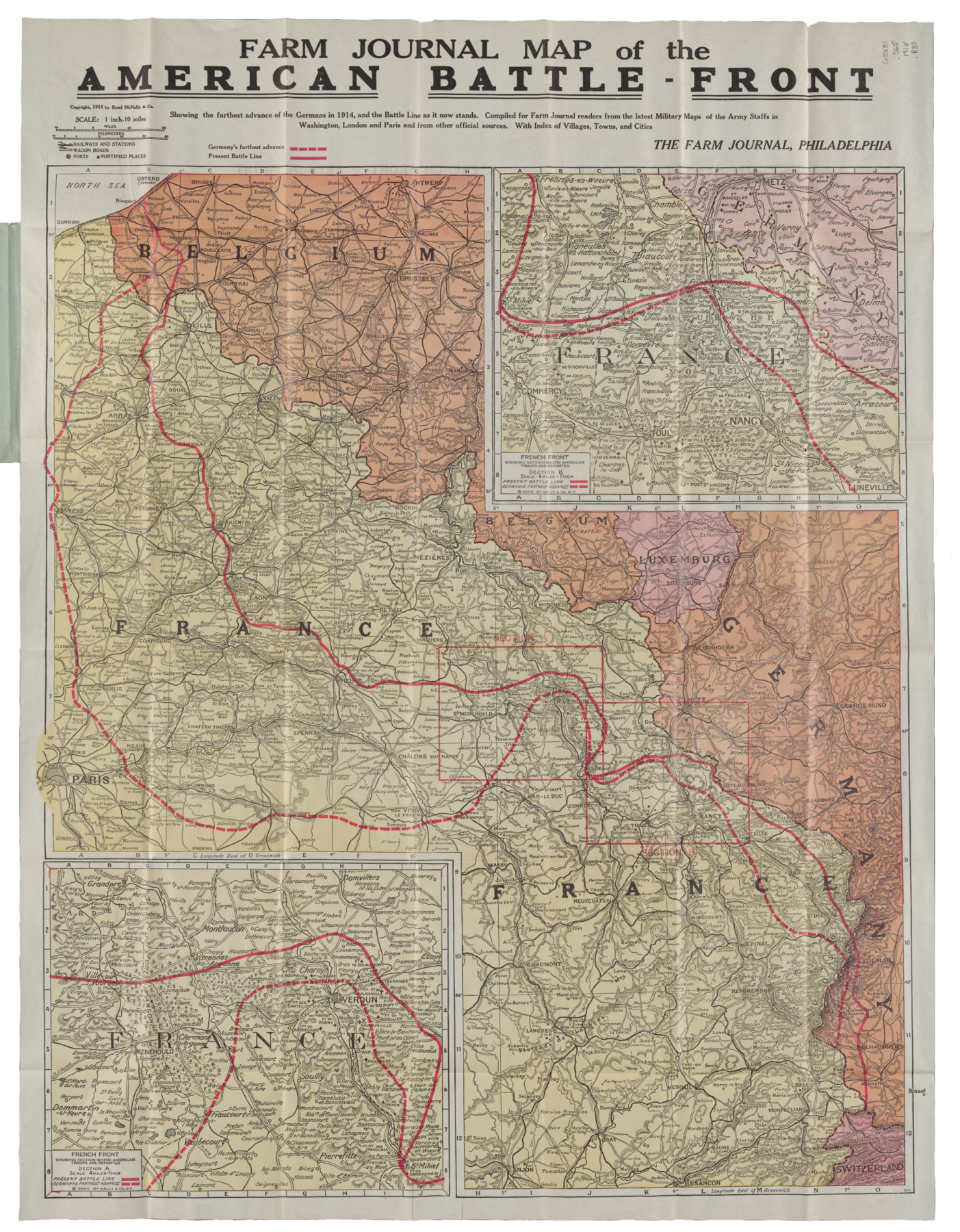

Mapping the War

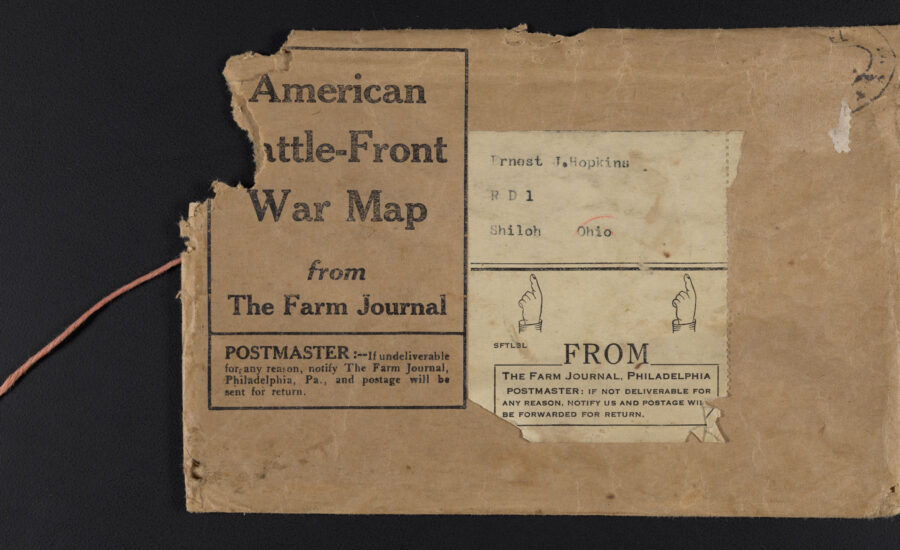

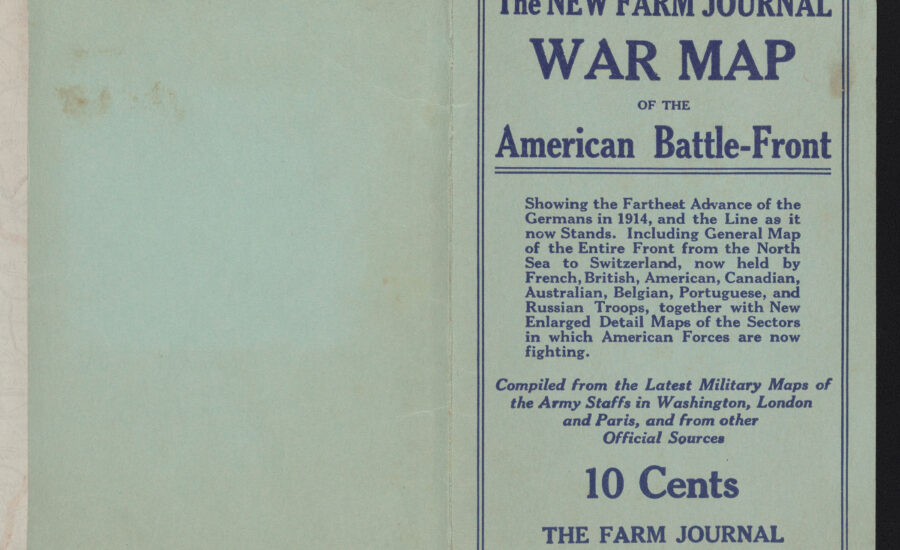

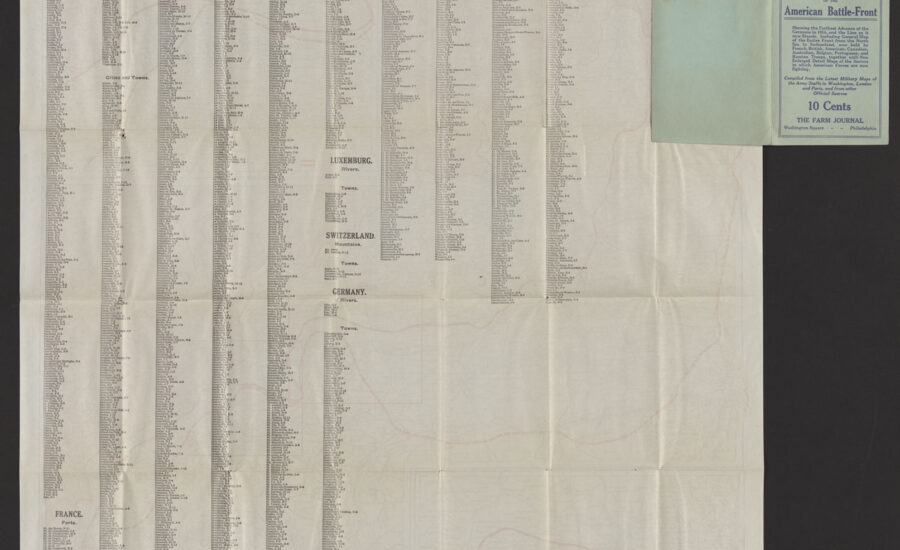

On the eleventh day of the eleventh month, a bit shy of the eleventh hour in 2022, Lew and Susan Hopkins handed Map Librarian Jenny Johnson a small, slightly mouse-chewed, modest brown envelope. The envelope was addressed to Lew’s paternal uncle, “Ernest J. Hopkins, R.R. 1, Shiloh, Ohio.” Inside was a thin, folded map from 1918 titled, “American Battle-Front War Map” printed by the Farm Journal.

During WWI, many companies produced commercial maps to both educate Americans on the geography of the various fronts as well as illustrate the progression of the war. Johnson believes the map is “an important and unique artifact about how Americans on the home front were kept abreast of developments in Europe. I suspect that Ernest’s map is the only copy of this map in a library in the United States.”

Ernest, who turned thirteen the summer of 1918, sent ten cents to the Farm Journal for the map. Born on a small farm in Richland County, Ohio (roughly halfway between Cleveland and Columbus), Ernest had a maternal uncle who served in the war in France, and an aunt who served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps in base hospitals in the U.S.

Lew is a professor emeritus in the department of Urban and Regional Planning and spent many hours in the Map Library. Susan has done genealogical research there as well. Inspired by an article in the Friends of the Library newsletter, Susan contacted the Map Library when Lew’s family began identifying how to pass along a trove of family documents and items to appropriate archives. “Sometimes we can be grateful that others did not downsize too thoroughly and throw old stuff away,” she said. Donated by Lew and Susan Hopkins.

A Historic Flight

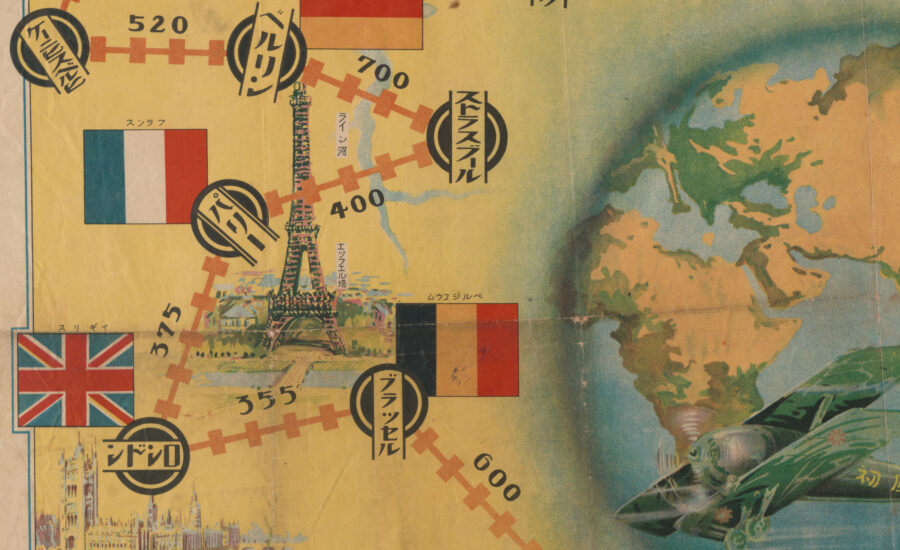

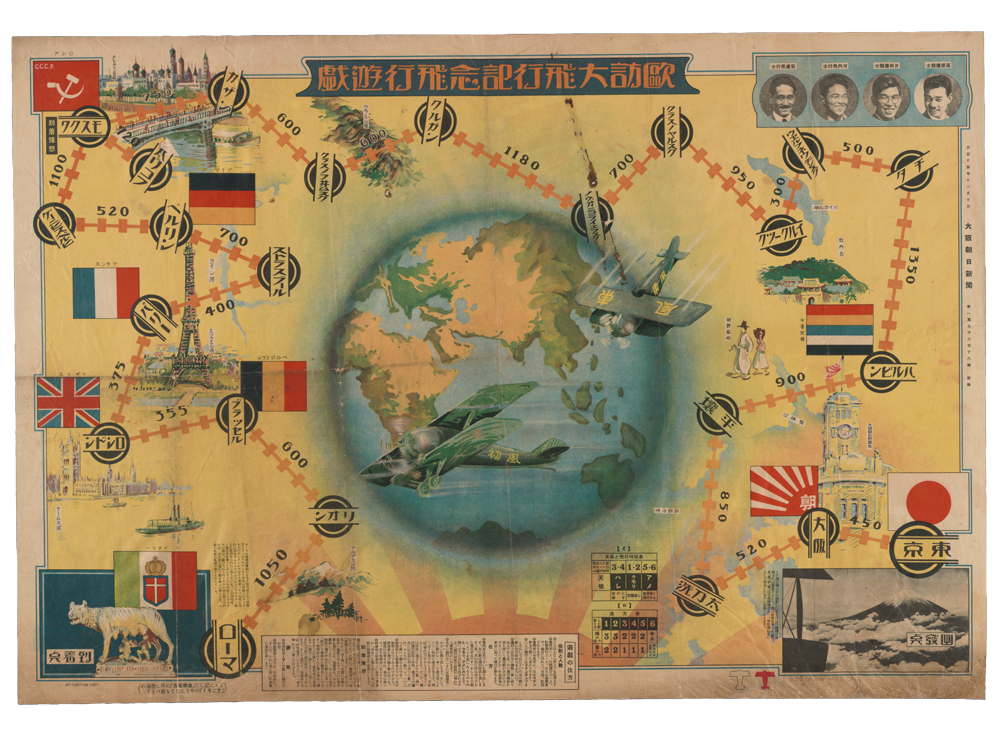

When taking an initial look at this piece of art, it is tough to discern exactly what it is. A map? Art? Ambitious military plans? Upon deeper investigation, a sugoroku gameboard (a game like Chutes and Ladders) materializes—serving as an unassuming time capsule housed in the Illinois Map Library.

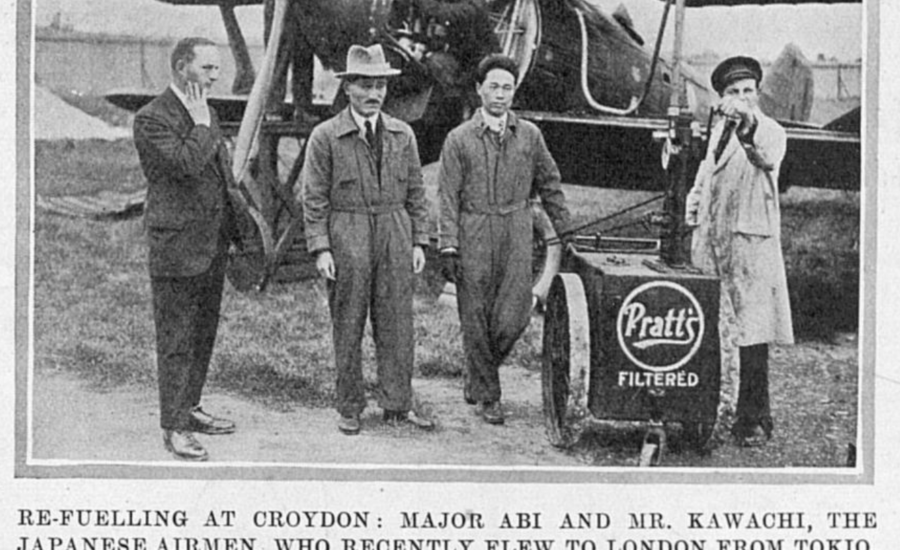

The Asahi Shinbun Newspaper printed the gameboard on December 10, 1925, to celebrate a remarkable aviation feat accomplished by four Japanese airmen. The flight crew made the 10,293-mile trip from Tokyo, Japan, to Rome, Italy, in just over one hundred flight hours, making stops to refuel and rest. (For comparison, Lindbergh’s 1927 nonstop crossing of the Atlantic totaled 3,600 miles in just over thirty-three hours.) The flight, backed by the newspaper, shined a light on Japanese aviation advancements.

The game starts at the top of Mt. Fiji and then onto The Asahi Shinbun Newspaper building in Osaka. The flight path continues over hilltops and lakes, through the Ural Mountains, past the Kremlin Palace, over the Rhine River, around the Eiffel Tower, past the River Thames and atop the Alps before finally arriving in Rome. Players advance through the game, experiencing the stops and sights the pilots would have seen during their journey.

While many Americans may not have heard of this feat–learning more about the Wrights, Earharts, and Lindberghs of our Western world–this momentous accomplishment of early aviation lives on in the symbolic journey players take through the sugoroku board.

This story was published .