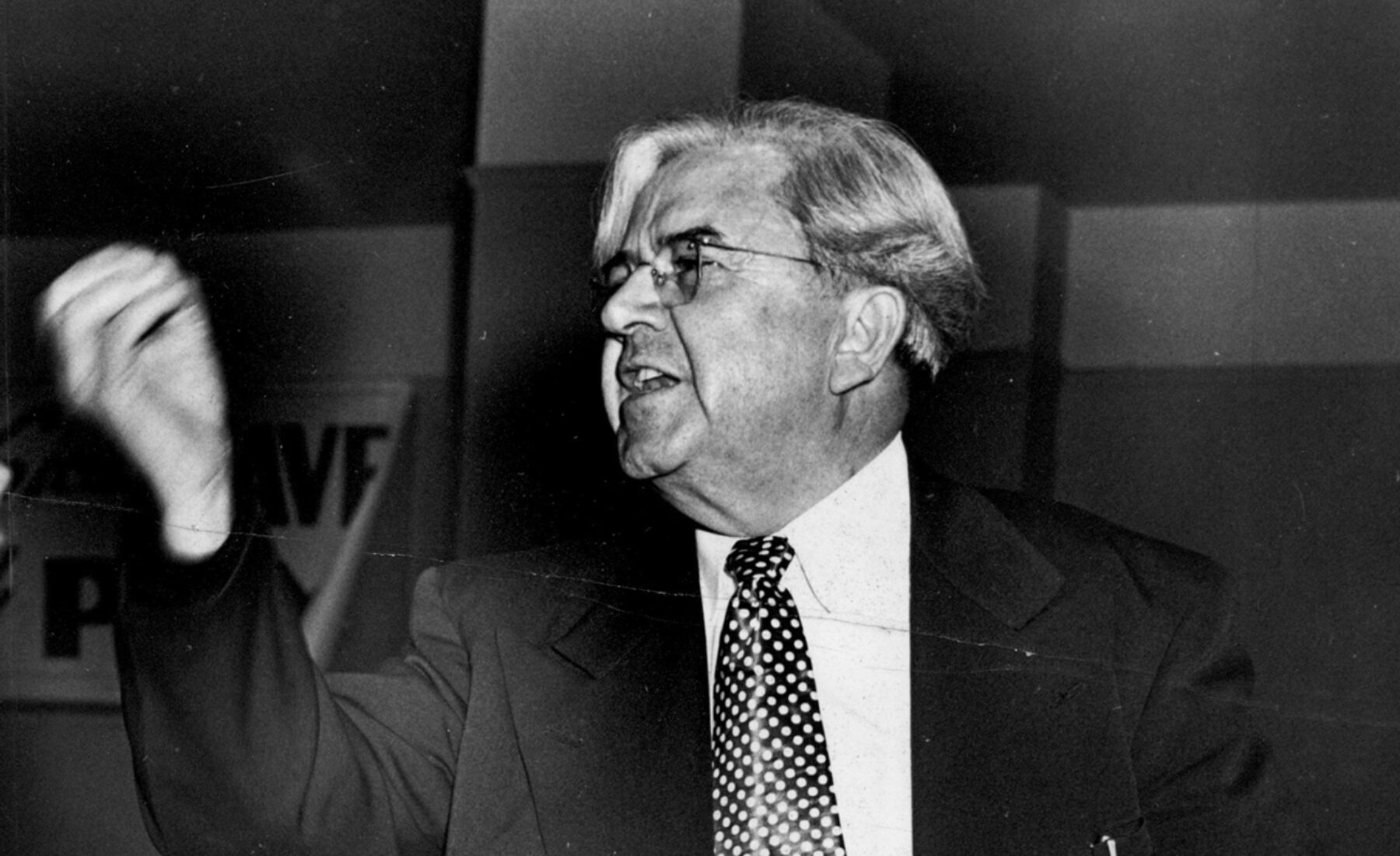

On a cold February night in 1935, angry workers—some sitting on windowsills, some hanging out of doorways—gathered around City Hall in Decatur, Illinois. They were reeling from the violence that had erupted days earlier when police unleashed tear gas on a small group of strikers from the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. One woman ended up in the hospital and lost her sight; others ended up in jail.

To make matters worse, the courts issued an injunction against future assembly by the women—a fact that incensed Reuben Soderstrom, then president of Illinois’ largest labor organization.

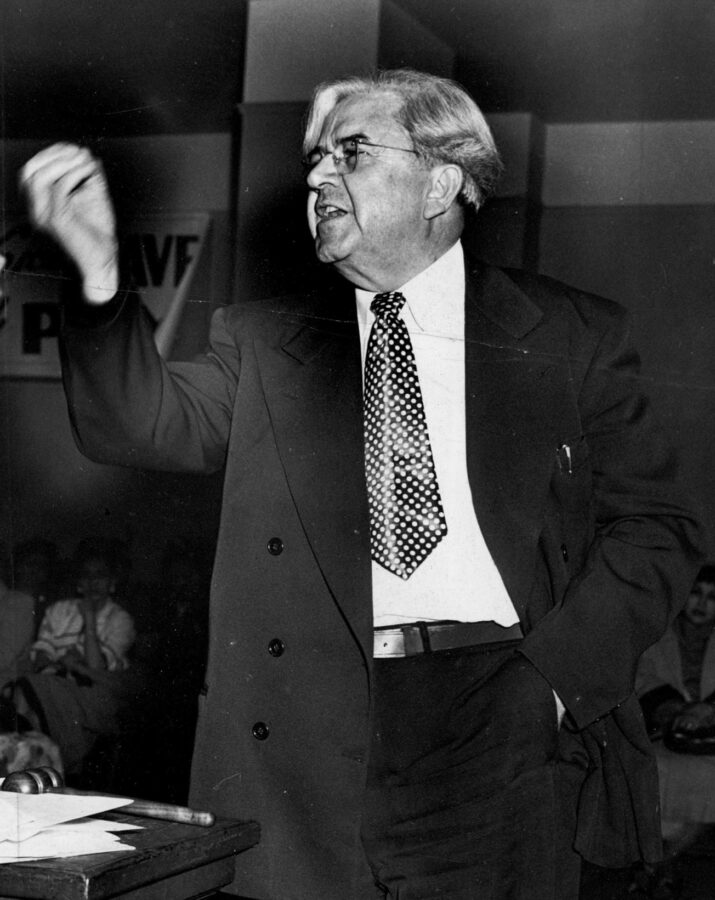

Soderstrom encouraged the workers to violate the injunction and did so himself when he joined the large gathering in Decatur and gave a rousing speech.

“I announced from the platform that I was defying that injunction,” he remembered in a 1958 interview for the University Archives. He told the gathered workers, “I hold that court in contempt, and I hold that injunction in contempt. And if I didn’t … I’d hold myself in contempt.”

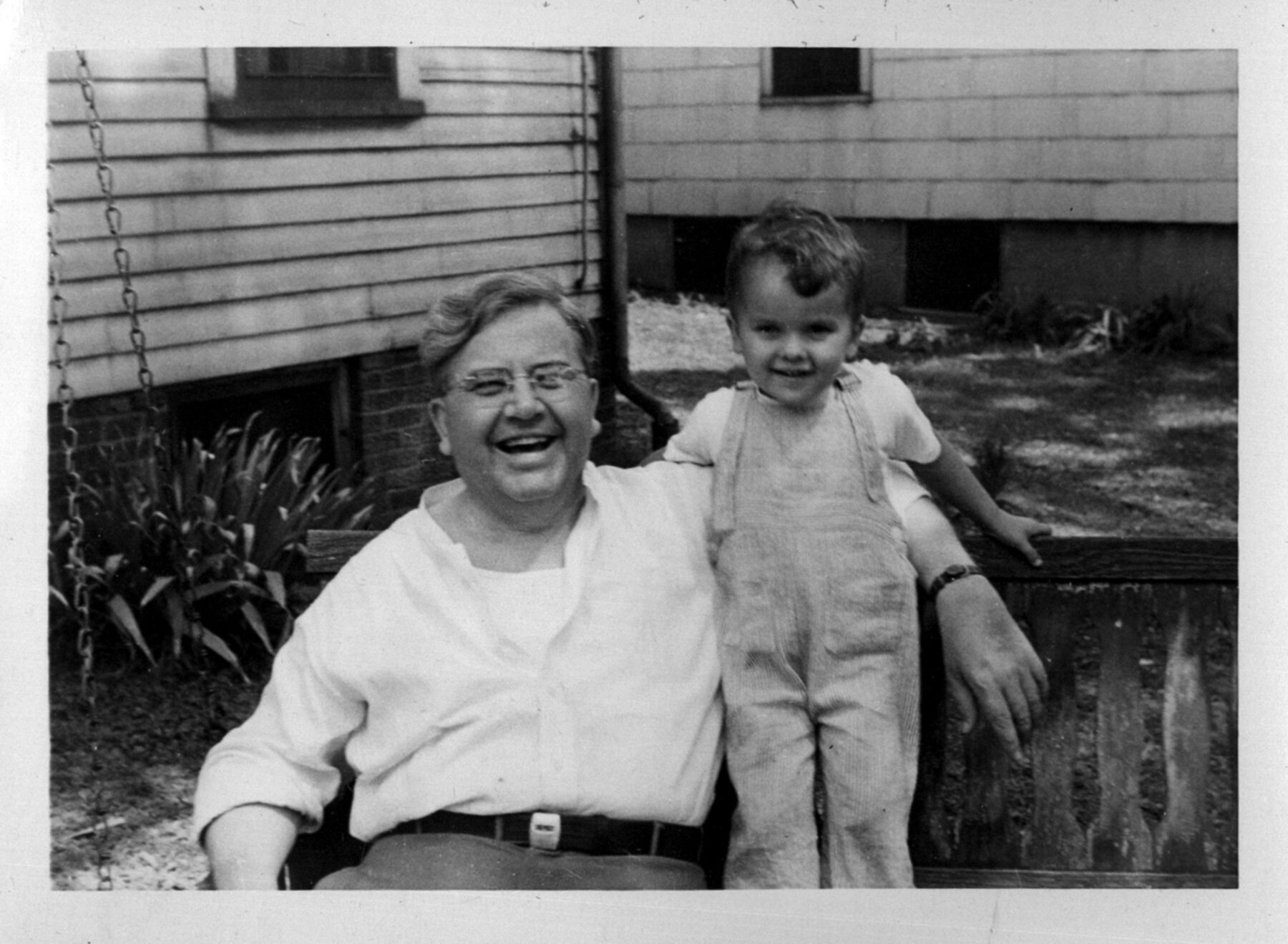

Over the course of Soderstrom’s life, 1888-1970, the United States saw the most dramatic changes to how we work in our history—and he had a front-row seat.

As a representative in the Illinois House for sixteen years, he was a powerful advocate for the working class, introducing progressive legislation that addressed issues such as equal pay for women, better unemployment insurance, workers’ injury compensation, and child labor laws.

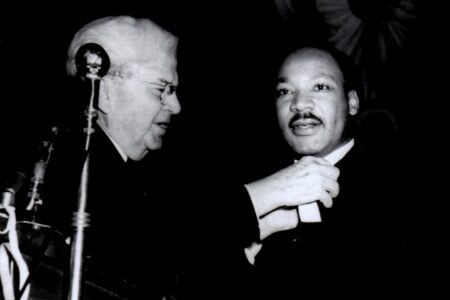

Soderstrom also served as president of the Illinois chapter of the AFL-CIO, the national labor organization which has served millions of workers. He held this uniquely powerful role from 1930 until he passed away in 1970. Illinois had an extremely visible and vocal labor movement, and presidential candidates, from Roosevelt to Kennedy, sought his support. President Johnson invited him to the White House.

Soderstrom’s passion for American workers’ rights, safety, and ability to strike against unfair conditions had its roots in personal experience. At the height of the Industrial Revolution, when he was only nine years old, Soderstrom was sent to work in a blacksmith’s shop nearly one hundred miles from his family in Minnesota to pay off his parents’ taxes. As a young boy, he continued working, fetching water for trolley workers, and assisting glass blowers in a bottle factory. He ultimately built a career casting metal type in a print shop, continuing to work in the evenings even after he began his political career.

While his formal schooling was cut short, education always remained important to Soderstrom. As a young man, he was a regular presence at the public library, reading voraciously. And as a legislator and president of the Illinois AFL/CIO, he lobbied for the establishment of a labor college. In a 1945 convention speech, he said it would, “serve the working people of Illinois just as the College of Agriculture at the University of Illinois serves the farmers of this state.”

Originating in the halls of labor and as the chairman of the Education Appropriations Committee in the Illinois House, Soderstrom put forth legislation to secure the funding that led to the creation of the School of Labor and Employment Relations, then called the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations. He was also instrumental in fundraising for a building dedicated to the school.

Generations later, the Soderstrom family remains closely tied to Illinois, both as alumni and donors. In the 1970s, as a member of the Illinois House, Reuben’s son Carl, Sr. (LAW ’43) sponsored funding for the law school addition. In 2019, Reuben’s grandson Dr. Carl Soderstrom, Jr. (LAS ’64), who earned his medical degree at our Chicago campus in 1967, spearheaded the family’s support of the installation of a visionary statue of Reuben and the renovation of the plaza behind the LER building. The family also endowed the Reuben G. Soderstrom International Labor Relations Professorship, which was awarded for the first time this year.

When Carl, Jr. reflects on Reuben’s life, he remembers a humble family man who valued honesty, hard work, and education. “He had a purity of purpose, and was a great inspiration,” he said.