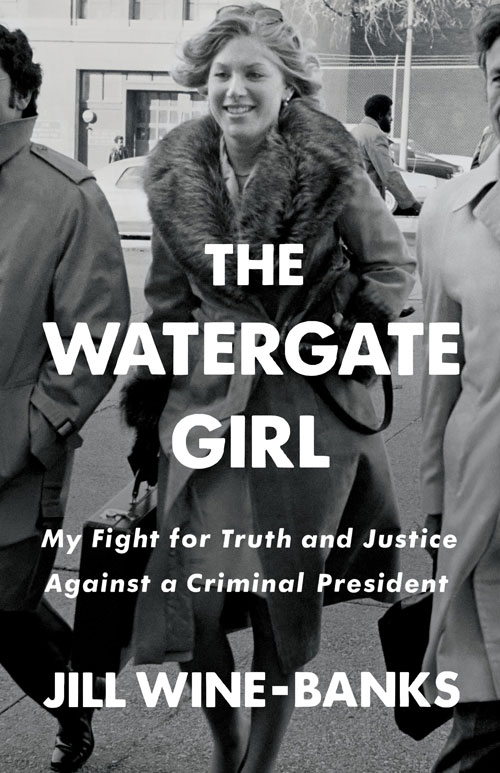

Jill Wine-Banks (MEDIA ’64) found herself center stage in one of the most dramatic political moments of the twentieth century — the Watergate trial that proved Richard Nixon’s top aides had obstructed justice and that led to the president’s resignation. Only thirty at the time, Wine-Banks was one of the Watergate special prosecutors and became famous for her cross-examination of Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods. Her cross-examination proved Woods did not mistakenly erase eighteen-and-a-half minutes of a key tape recording that would have substantiated Nixon’s involvement in the scandal.

Now in her seventies and a legal analyst for MSNBC, Wine-Banks is writing her memoir that will be published in 2020. In those pages, she reflects on a remarkable career that has been devoted to equity and justice. She has shattered glass ceilings not only for women in the legal profession but in spaces that, as she was coming of age, were particularly closed to women: the organized crime unit of the Justice Department, the top echelons of the U.S. Army, and boardrooms at international companies. As she recalls, she often found herself to be the only woman in the room.

✦ ✦ ✦

One of the nation’s most notable lawyers nearly didn’t become a lawyer at all. When Wine-Banks was coming of age on Chicago’s north side in the late 1950s, career opportunities were limited for women. Girls were encouraged to become teachers, nurses, and homemakers. It was hard to come by role models who followed other career paths.

Wine-Banks remembers her father, an accountant, had one female client who broke the mold — she was an occupational therapist. Without really knowing what an occupational therapist did (or that she would have to dissect a cadaver her sophomore year), Wine-Banks decided to major in occupational therapy when she arrived on campus.

It didn’t take her long to recognize that journalism was a better fit.

Upon graduation, however, she found that it was very difficult to get assigned to anything but the women’s pages. Hoping for a better beat, she entered law school at Columbia, thinking a law degree would convince editors she was capable of more. Instead, she found a field she loved.

The arc of Wine-Banks’ coming of age mirrored the rise of the civil rights movements in the United States, and while that gave her ample opportunity for advocacy, it also put up barriers along her path.

When Wine-Banks entered Columbia Law School in 1964, a quota limited the number of women in the class to 5 percent of the total enrollment. “This was during the Vietnam War, and we were told somebody was going to die because we took their place in the class,” she recalled. “When we were interviewing for jobs, we were asked questions like, ‘How would your mother feel about you coming home late? Do you plan to have children? What kind of birth control do you use?’ These were legal questions at the time, and we felt we had to answer them or we wouldn’t get hired.”

Undeterred, Wine-Banks built the kind of career that seemed impossible at the time. She launched her career in the organized crime unit of the Department of Justice, where although she was hired as a trial lawyer, she was not assigned a trial until she demanded one.

“I didn’t get my first trial at the Department of Justice until long after the men I started with were getting trials. When I confronted my boss, he said, ‘But you’re a girl, and it is much more dangerous for you to be in the trial court than it is for the men.’ If I hadn’t gone to him, he would never have assigned me to one. And if that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have been a Watergate prosecutor, and then all the doors that opened for me because of Watergate would not have opened.”

“I didn’t get my first trial at the Department of Justice until long after the men I started with were getting trials. When I confronted my boss, he said, ‘But you’re a girl, and it is much more dangerous for you to be in the trial court than it is for the men.’ If I hadn’t gone to him, he would never have assigned me to one. And if that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have been a Watergate prosecutor, and then all the doors that opened for me because of Watergate would not have opened.”

Wine-Banks hopes the experiences she shares in the memoir shed light on how far society has come, while illustrating the work left to do.

“I hope people who read the memoir will see what I did and understand that they can do the same thing,” she said. “However, it is important to recognize there are still significant hurdles. You have to face them. If you ignore them, you will continue to be ignored.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Perseverance would become a theme in her career. Her success at the Department of Justice led to her selection as one of the three Watergate special prosecutors. After the trial, she moved on to private practice, but it wasn’t long before she was selected for another prestigious position — General Counsel of the United States Army. In this role, she was given four-star general status and was responsible for over two thousand military lawyers.

Wine-Banks was appointed to this position by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. At the time, women who enlisted joined the Women’s Army Corps, a branch established during World War II to address the need for more soldiers. This branch, however, was not integrated into the regular army, and the women were not only separated for basic training but also limited in the number of jobs they could hold and the rank they could achieve.

During her tenure, Wine-Banks worked with the team that proposed legislation to fully integrate women into the army, an undertaking of which she is very proud. She is also proud that her successor to the General Counsel position was a woman.

Wine-Banks was not yet forty and had already accomplished much in her career, and went on to achieve even more. She became Illinois’ first solicitor general and then deputy attorney general; she was the first female executive vice president and chief operating officer of the American Bar Association; she worked in international business development for Motorola and Maytag; she was the chief officer of Career and Technical Education for the Chicago Public Schools, where she helped to create DeVry Advantage Academy High School, Chicago’s first early college program; she was appointed to a Defense Department subcommittee on sexual assault in

the military.

She continues this pace today, making near-weekly appearances on television and speaking at numerous events.

“It is wonderful to look back and to say that I have opened doors for other women,” Wine-Banks said. “But we have a lot more work to do. I want true gender equity, not just in terms of pay but in terms of power. I want to see the same number of women as senior partners at law firms. I want to see the same number of women in Congress. I want to see everyone treated fairly in the court.

“I will keep on fighting that fight.”

This story was published .