Radios squawk, issuing the murmurs of disembodied voices as a handful of students file into the small, fluorescent-lit classroom. The background noise continues as they take their seats, but the students seem unfazed.

At the front of the room, a detention officer stands at a podium, addressing the students one by one.

“It’s time for reflections. What was your goal today?”

“Ignore things that do not pertain to me,” mumbles a boy in his mid-teens.

“Keep my talk appropriate,” another says.

“Display appropriate attitude.” This from a girl in her early teens.

“You had a really good day,” the officer returns. He gives each resident their points for the day, as well as comments from other staff members, then lowers the volume on the radio, and turns the podium over to Stephen Fleming.

Fleming is at the Champaign County Juvenile Detention Center (JDC) on a Monday night to teach science. He’s part of a group of graduate students in the Neuroscience Program at Illinois who bring STEM education to the JDC on a weekly basis.

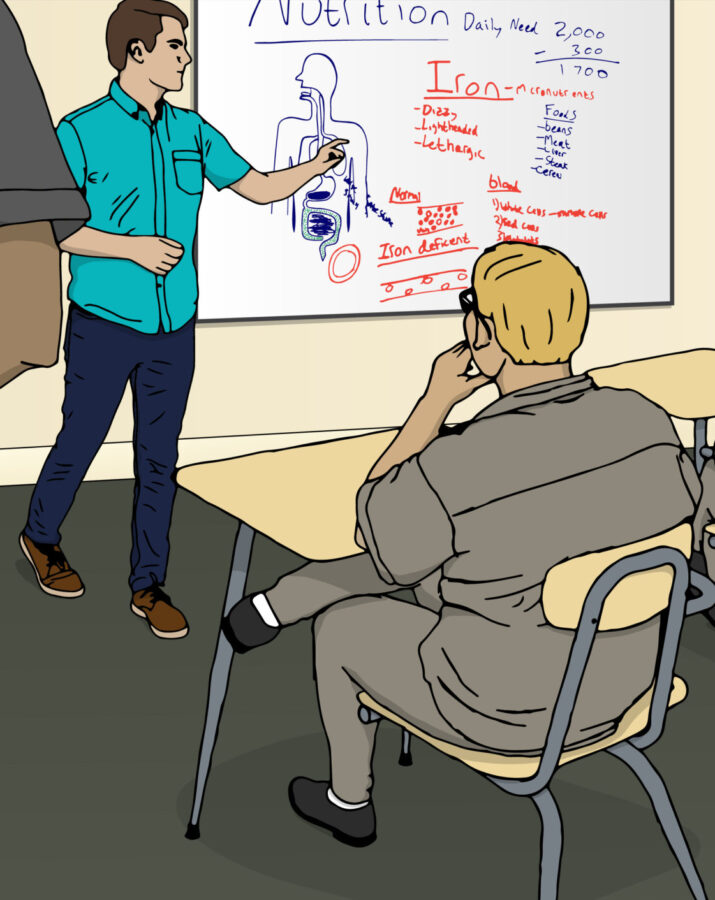

As he gets started with his lecture on human nutrition, the students tune in slowly. Pretty soon, they’re speaking up, asking and answering questions, becoming engaged.

“Why do we eat?” Fleming asks.

“To stay alive!”

“To keep our bones strong.”

Fleming continues with a discussion of major nutrients and where they’re absorbed in the body, chalking a rough diagram on the blackboard. As the lesson veers toward the digestive tract, talk inevitably turns to poop, reminding Fleming that despite the setting, these kids are still just kids.

✦ ✦ ✦

The Juvenile Detention Center Outreach program, conceived by neuroscience student Ian Traniello, has been running for five years. To date, roughly a dozen neuroscience students have participated, most of whom had never taught behind bars. Now, the JDC outreach team has been on several local panels discussing their outreach work, presented posters at the annual Society for Neuroscience Meeting, and had their work highlighted in Science.

Traniello was first exposed to prison outreach at a previous institution, where he learned that prisoners who received letters from friends, family, or even complete strangers were less likely to be subjected to violence while incarcerated. He says receiving correspondence from the outside world can lead to better treatment for these individuals because it shows someone out there cares, and is paying attention.

“I really had no concept of what was going on behind bars,” he says. “And that’s the exact function of prison, to disappear folks. It’s a convenient mechanism of sweeping people aside. In the context of juvenile incarceration, I wondered what it says about our society, that we lock up children.”

Motivated to humanize and serve this forgotten sector of society, Traniello reached out to the JDC soon after enrolling at Illinois and was granted access almost immediately. He put out a call to his fellow students to help, and quickly got dozens of responses. Today, there are about eight regulars in the program, some delivering Monday-night lectures and others bringing in hands-on materials for lab presentations on alternate Wednesday nights.

In Illinois, children between the ages of 13 and 17 can be detained after arrest in a county juvenile detention center. They’re there until their court case is called or they are serving a court-ordered sentence, which can be a matter of days or months.

During the day, detainees spend about eight or nine hours each day in common areas for school instruction, free time, recreation, and meals. The rest of the time, they’re in their cells. They can read, draw, write, or study, but it’s mostly a lot of time waiting around, worrying about upcoming court cases and missing life on the outside.

All that worrying can take a toll. Research links the stress of incarceration with increased rates of depression and suicidal ideation, according to Rebecca Ginsburg, associate professor in education policy at Illinois and director of the Education Justice Project, a college-in-prison program for adults at the Danville Correctional Center.

Ginsburg advocates against the very existence of juvenile incarceration, but barring immediate criminal justice reform, she says, “At the very least, we need to support the mental health, well-being, and spirit of people who are inside and provide them opportunity, especially as children, to continue to grow and develop physically, emotionally, and spiritually. The science program addresses some of those needs.”

✦ ✦ ✦

“I’m stressed,” one seventeen-year-old says. “The science program lets my mind escape, no matter what they’re teaching.”

That response is common among the detainees, many of whom have no particular interest in science per se and who wouldn’t opt to sit through a forty-five-minute science lecture if they had anywhere else to be. For the most part, they see the science program as entertainment, distraction. Or “kinda fun,” in the words of a sixteen-year-old detainee.

Despite their passion for science and STEM education, some graduate students in the program are just fine with being seen as entertainers.

“If these kids can remember that detergent breaks up lipids and that’s why food coloring spreads in milk, that’s a win. If they remember that rocks are made of minerals, that’s a win. But we certainly care more that they are excited about something, even just for the moment,” says Rachel Gonzalez, who teaches in the lab group on alternate Wednesday nights.

Coltan Parker, also a lab instructor, says, “They’re still just kids. They just want to goof around, they want to joke. That’s a lot of what we provide. We’re at the extreme of science-y nerdy types, and they get to play off of us a little bit, which I embrace.”

Gonzalez adds, “It’s a lot of fun when you see a look in their eyes where they’re like, ‘I’m humoring this dork.’”

The classes may not alleviate detainees’ stress for long, but they represent a bright spot. And, behind bars, bright spots matter.

“Young people who are locked up need as much contact and resources and reminders of their humanity and their capacity and their talent as they can get,” Ginsburg says. “And you never know. If their exposure to STEM fields at JDC allows these kids to see a way into science, that would be a good thing for them and for society.”

✦ ✦ ✦

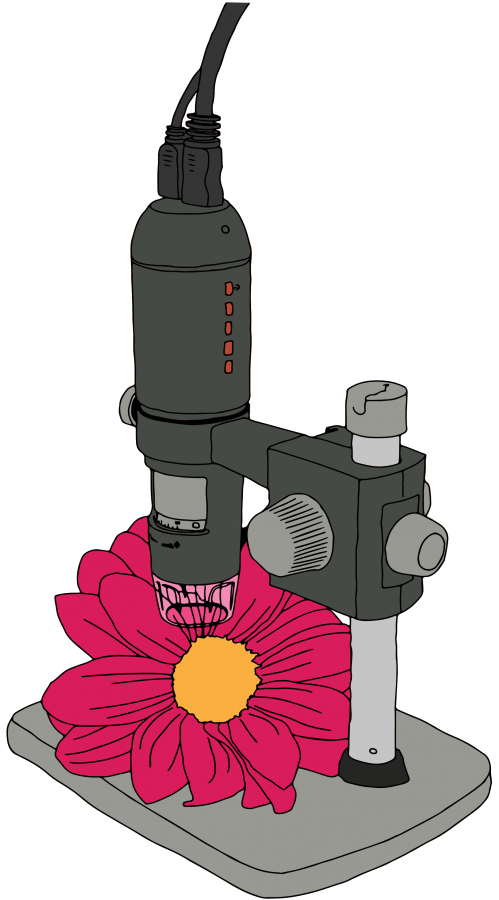

On a recent Wednesday night, Parker and Gonzalez hook up a dissecting microscope to a large flat-screen TV on the wall of the JDC classroom. They open a small box containing everyday objects – a flower, bark, soil, leaves, snack foods, tin foil – to let the kids practice using one of the most important tools in science. As the kids file in, a torn marshmallow is displayed on the screen. It’s vaguely greenish, lumpy, pocked.

“Can anyone guess what this is?” Gonzalez prompts.

The group is quieter tonight. The ice hasn’t broken yet.

Then someone shouts, in a disgusted tone, “It looks like somebody’s tooth decay.” The room erupts in laughter and they settle in. For the next 45 minutes, there are more guesses, more objects, and a bit of light discussion on the scientific method and its tools. By the time they file out, heading to the showers and then to bed, the kids look lighter.

✦ ✦ ✦

Marla B. Elmore, assistant superintendent at the JDC, says, “Over the years, the grad students have become good at not talking way over the kids’ heads, but also not dumbing-down the material too much. I think they present the material in a way that challenges the kids.”

The learning curve is understandably steep. Many graduate students have no previous teaching experience, or have taught only in the context of an institution of higher education. JDC detainees are middle- and high-school age, and, unlike university students, they’re not there on purpose. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t intelligent and engaged.

“There have been a bunch who have been like, yeah, I’m getting an A in this or that subject at school,” Traniello says. “I like to see them taking responsibility for the fact that they’re intelligent people. Their current circumstance doesn’t invalidate their drive to learn, or the fact that they deserve a solid education.”

Then there’s the challenge of kids constantly coming and going from the detention center, preventing continuity in the lessons. Ginsburg teaches college courses in adult prisons, where sentences are longer, but her program deals with similar issues. “We have to build our curriculum so that if someone stays in for two years versus three weeks, they’ll both get something out of it.”

But when asked about the most difficult aspect, Traniello says, “The hardest thing is that jarring return to reality. When you’ve had a really good night, when they’ve taught us as much as we’ve taught them, when you’ve had a really good discussion. It’s hard to believe not only are these kids incarcerated, but that they’re only teenagers, confidently speaking to you about something they hadn’t even heard of an hour before. Then you walk out, and they don’t walk out. There’s no other experience like that in the world.”

✦ ✦ ✦

To get involved in the science program, contact Ian Traniello or visit the JDC Outreach website. To volunteer with the Education Justice Project, contact Rebecca Ginsburg. To offer another program at the JDC, contact Marla Elmore.

This story was published .