In 1864, Private Thomas Halligan had been fighting in the Union Army for three years. The forty-one-year-old was stationed with his regiment in Petersburg, Virginia, just twenty miles south of Richmond, the Confederate capital. Union and Confederate armies had been battling among a labyrinth of trenches for months. Ultimately sixty thousand soldiers would lose their lives here in what would become known as the Petersburg Campaign.

The seemingly interminable Civil War was the bloody backdrop for the upcoming presidential election to be held that November. President Abraham Lincoln was becoming increasingly wary of his chances for reelection against Democratic opponent George McClellan. To rescue his campaign, Lincoln felt he needed to make sure the millions of voter-aged, White, male soldiers dispersed throughout the country and far from their homes—like Thomas Halligan—were able to vote.

This election, held in a divided nation, is considered a seminal moment in American voting history. It is the first time the states in the U.S. allowed a widespread use of absentee or mail-in voting.

It was as complicated then as it is now.

✦ ✦ ✦

Rules around voting have always been controlled on a state-by-state basis, not at the federal level. Regulations, and in turn participation, vary widely by state.

“The number one rule of American elections is federalism. That means there are different rules everywhere—way more than fifty sets of rules,” said Brian Gaines, political science professor. “When you compare different traits about an election, one state will have partisan registration, but won’t require identification. Another one has an identification requirement, but without partisan registration. And so on.” While Gaines was referring to today’s voting landscape, this level of inconsistency has been the case since the nation’s beginning.

Although the vote was denied to many Americans at the time, some states had passed legislation to ensure soldiers—often White men who were over 21—were able to vote. States like Missouri, Wisconsin, and Minnesota had already passed acts granting absentee voting for soldiers in time for the 1862 mid-term elections.

By 1864, though, intense pressure was coming from the Lincoln administration and the War Department to ensure suffrage among White soldiers. Pressure was also coming from soldiers who wanted to vote. Those from states like Illinois were frustrated about being sidelined because of intense partisan fighting over the process.

“We, as a regiment, brigade, and in fact as an army of veteran Illinoisans, fighting for three long years the battles of our country, feel that the act of the Illinois Copperhead [Democratic] Legislature, in not permitting soldiers to vote, is base, contemptible, and an insult to men who have voluntarily offered their services, and lives if need be, to put down the rebellion,” wrote a soldier from Illinois in early September in a letter to the Chicago Tribune. “The act of disfranchising us from the ballot-box will reflect sadly upon them by and bye.”

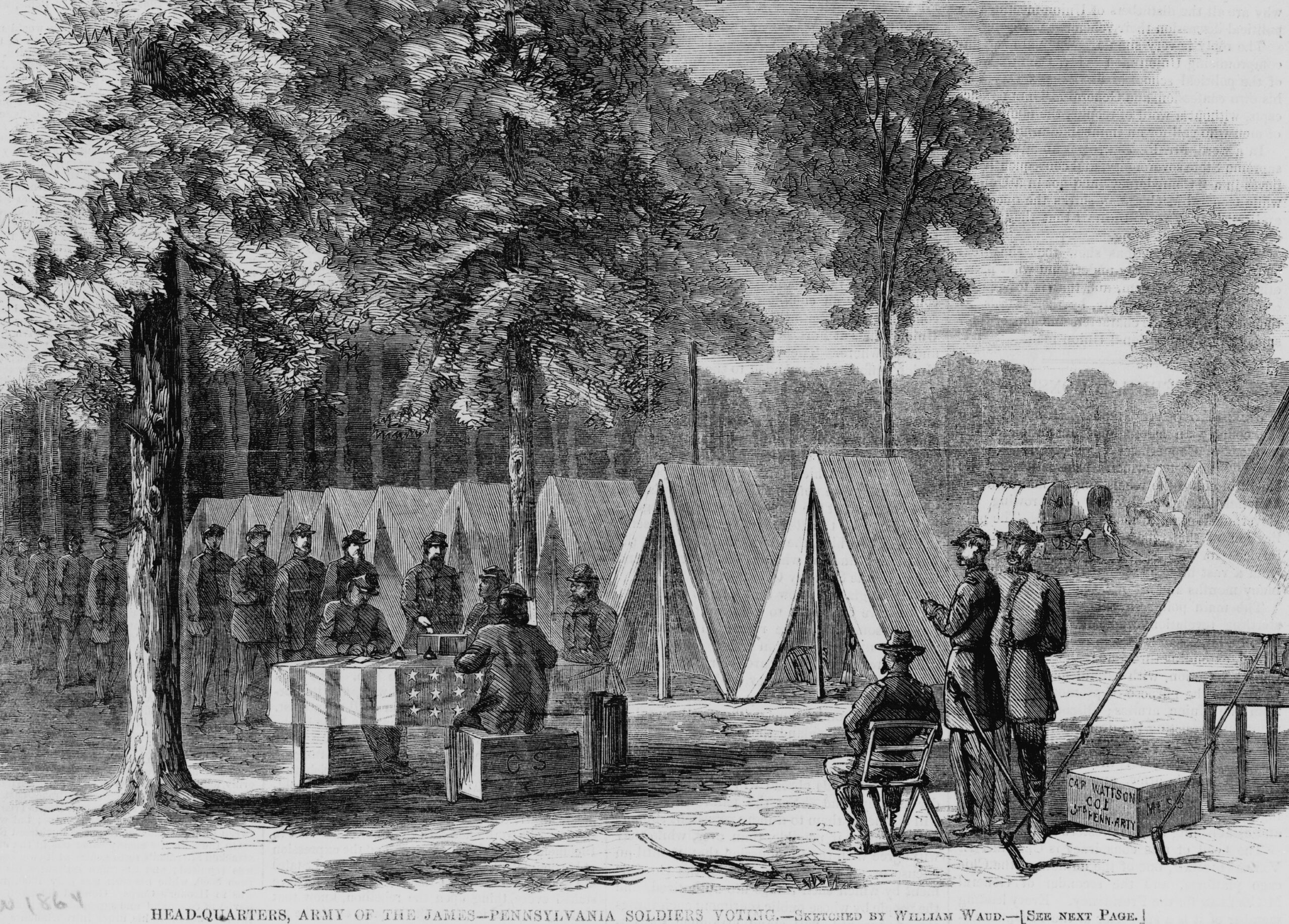

If an active-duty soldier was part of a regiment from a state that allowed absentee voting, there were a few ways to vote. Some states allowed mail-in voting. When the military could, it furloughed soldiers so they could return home to cast their vote. States like Maine passed legislation allowing absentee voting in 1864, and New York passed legislation to allow for proxy voting, where someone from your town cast a vote in person on your behalf. As a result, among the Union states was a patchwork of methods to enable the soldiers to “deliver” their vote. Illinois eventually did enact legislation, but not until after the election in 1865.

✦ ✦ ✦

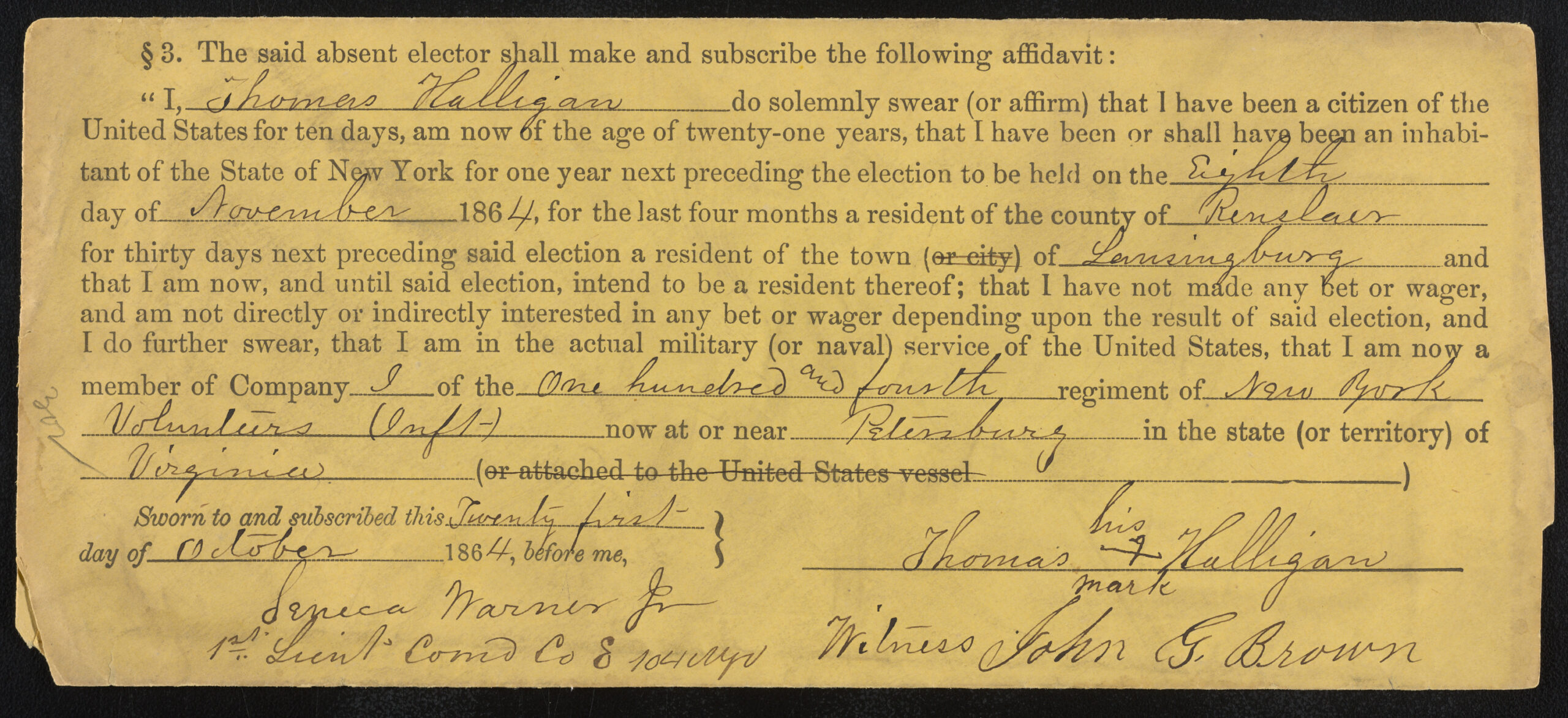

Halligan, stationed in Virginia, cast his vote by proxy more than five hundred miles from his home in Lansingburgh, New York. With an affidavit, a soldier’s power of attorney and in the presence of witnesses to ensure his identity, Halligan signed with an unsteady, shaky “x.” The actual “proxy” ballot is lost, but the documents accompanying them are part of the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections at the university. They serve as a testament to overcoming obstacles to preserve the still young republic.

Many soldiers mailed an absentee ballot from a camp on the front lines. The United States Postal Service had already been serving as an essential lifeline for soldiers far from home. For many Americans, mail was the only affordable way to communicate over long distances.

“By 1864, a lot of these regimental camps already had a system set up to collect and send mail out and to receive incoming mail and then distribute it,” said L. Bao Bui (LAS ’16), a Civil War historian. “These regiments of anywhere from 500 to 1000 soldiers already had the institutional knowledge and expertise and expectation that the mail would come in and go out no matter where the soldier was posted.”

In fact, the mail was so important to the soldiers that any disruption was seen as a personal affront. It was with this feeling that members of the military cast their vote by mail.

“They insisted having access to the mail,” Bui said. “This is how soldiers saw their lives as free people and to make sure that their voice in the election would be heard. You can glimpse into the mind of these Union soldiers, who are talking about the upcoming election in their letters and deduce they are heavily invested,” Bui said referring to his own academic research.

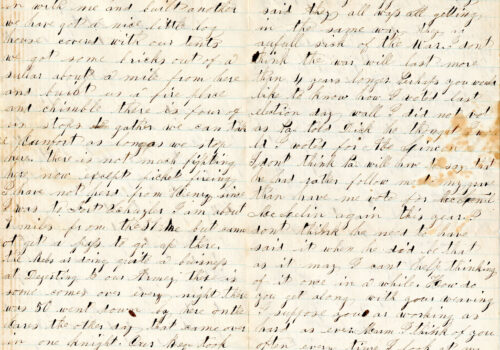

Halligan’s was one of the thousands of votes cast by Union soldiers in the field, like Corporal James D. Marshall of Maine. He wrote to his mother shortly after the election while stationed in Washington.

“Perhaps you would like to know how I voted last election day,” wrote Corporal James D. Marshall of Maine in a letter to his mother shortly after the election. “Well I did not vote as Pa told Dick he thought I would. I voted for Abe Lincoln.”

“Remember the right to vote was seen as the right to citizenship,” said Bui. “They saw the vote as an extension of themselves.”

✦ ✦ ✦

In the intervening 157 years since the Civil War, mail-in voting has persisted. When the nation encountered other calamities, like the 1918 Flu pandemic and World War II, voting by mail again become a topic of national debate, much like we’re seeing today.

Yet, mail-in voting has played a part in every election.

None of this is news to Amber McReynolds (LAS ’01, ’02), who is the CEO of Vote at Home Institute and Coalition, a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works with election officials to develop vote-at-home systems. Originally from Illinois (her father and grandfather are alumni as well), she now lives in Colorado where she was a lead innovator in Colorado’s vote-at-home system. Colorado has been voting at home for the past six years.

“I always say that the voting process was never designed for voters as customers. It was designed for political parties or candidates,” McReynolds said. “It was never was very thoughtful about making sure the customer experience was right for voters.”

With Covid-19 threatening to impact the number of voters willing to go to the polls and a limited staff to run them, she is often fielding requests from throughout the country to explain how and why mail-in voting is an important and reliable way to vote.

With Covid-19 threatening to impact the number of voters willing to go to the polls and a limited staff to run them, she is often fielding requests from throughout the country to explain how and why mail-in voting is an important and reliable way to vote.

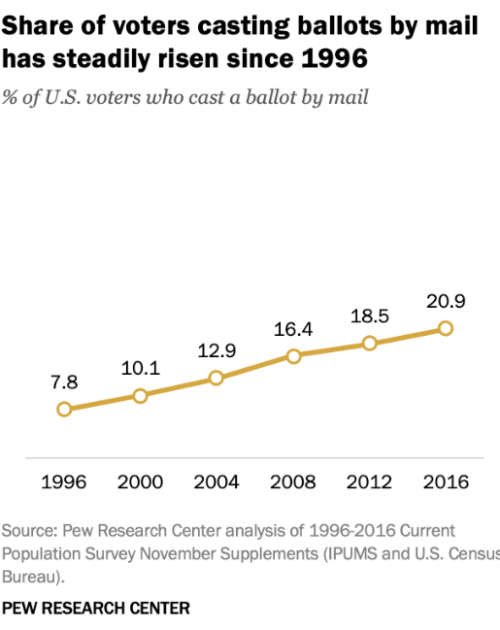

“A lot of people do not realize that voting by mail has been a thing since the Civil War, and what I think it demonstrates is that it came about to solve a problem that soldiers had,” McReynolds pointed out. “And what’s interesting about it is it’s the only method of voting that has continued to increase over a long period of time, because it provides access, and it solves logistical hurdles that people face.”

During the two past decades, the number of voters mailing in their ballots has been steadily increasing in the United States. In 1996, almost 8 percent of voters mailed in their ballots. By 2016, that number went up to close to 21 percent. However, there were wide disparities when looking on a state-by-state basis. States like Oregon, Utah, and Colorado vote almost entirely (97 percent) by mail, whereas in others, like West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, only 2 percent voters cast their ballot by mail.

Since the last presidential election, there’s been an overall expansion of mail-in voting throughout the nation in part because of the coronavirus. Today, three quarters of American voters will be eligible to vote by mail.

“I think it’s the best method we have today to give people a convenient option to vote at home and research issues on the ballot. It also gives people flexibility to decide when they want to make those selections,” said McReynolds.

“And to me, the more people who vote, the better off we are.”

This story was published .