Our campus is home to what now numbers in the millions of collected, created, donated, and unearthed objects from all over the world that are part of the university’s permanent collection. These treasures have been amassed through the hard work and generous philanthropy of countless students, researchers, professors, alumni, and friends. V

This occasional series uncovers and discovers the fascinating stories behind these curiosities—from items that reflect our natural and cultural history to art collections that represent all eras and mediums to the endless bounty of riches found in our library alone, including rare manuscripts, maps, and books.

These materials (displayed in museums and glass cabinets, tucked safely in boxes and drawers) are used by researchers as well as by instructors in classrooms and they do nothing less than tell the story of our collective humanity.

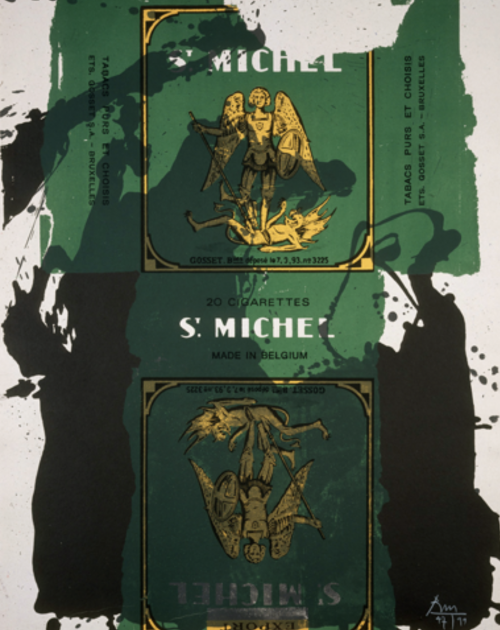

Making soup from scratch

Making soup from scratch

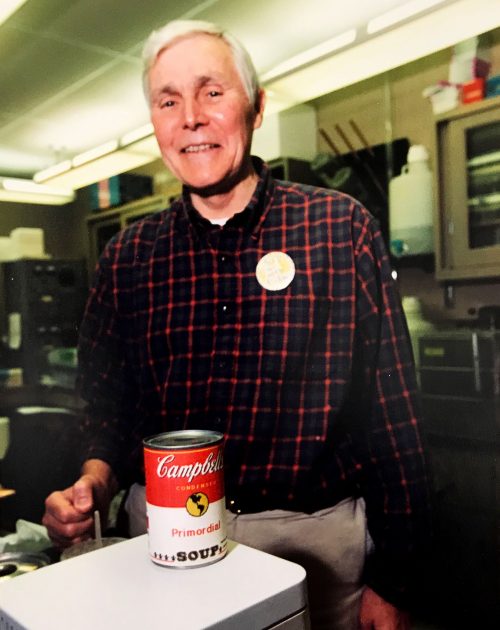

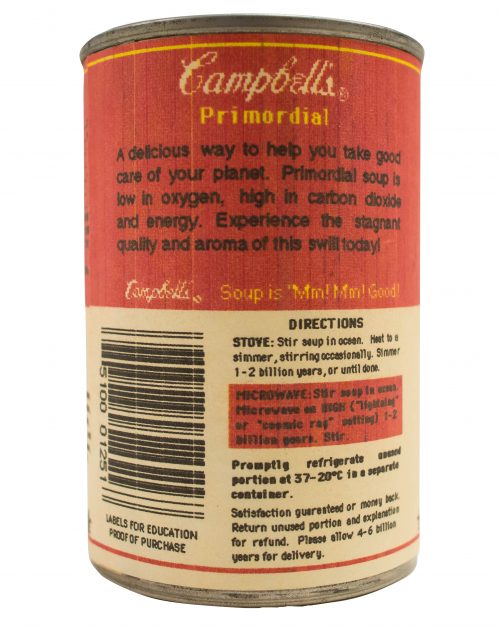

This can of “Campbell’s” soup belonged to Carl Woese. Yes, the evolutionary microbiologist giant on campus—who upended our fundamental understanding of the evolution of life—had an appreciation for the lighter take on his life’s profound work.

Physics Professor Nigel Goldenfeld, who worked closely with Woese, was well aware of his good sense of humor and was confident he would appreciate a story that highlighted it.

“Carl would say, ‘Good. I’m glad you’re writing about a clever scientific joke as opposed to another boring piece about the history of the origin of life,'” said Nigel. “He didn’t like being a figurehead. The last thing he would want is the university to put his head on a stick and parade it around.”

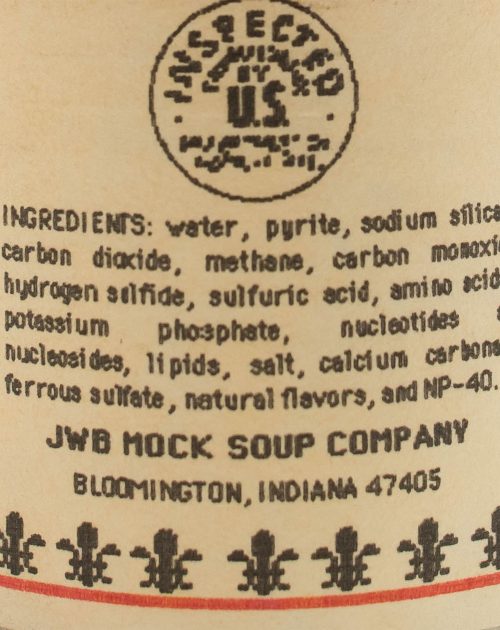

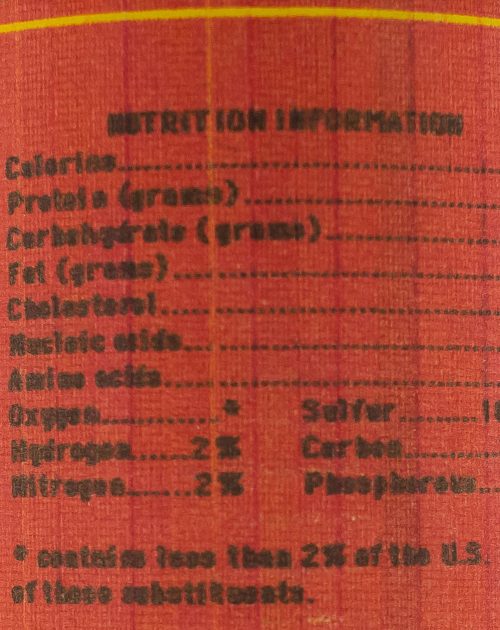

Shortly after Woese passed away in 2012, those he worked with in his lab at the Institute for Genomic Biology, which now bears Woese’s name, gave the contents of his lab, including the can of Primordial Soup, to the university to be archived. Jim Brown, a biology professor now at North Carolina State University, created the label when he was a post-doc for Norman Pace (LAS ’67), a colleague of Woese’s. A close examination of his tongue-in-cheek label reveals two competing theories about the origins of life, a nod to the lingering uncertainty about life’s early beginnings.

While Brown can’t recall having given Woese the soup, he was delighted to find out it was among Woese’s belongings. “I have to say, he’s kind of like my scientific grandfather, and he’s that way for a lot of people.”

Aiming for the stars

Aiming for the stars

Out of context and to the untrained eye, this bulbous piece of glass (blackened at one end, wires tethered to the outside) looks like an ornament meant for a holiday tree or a maybe a lightbulb for an antique lamp.

This treasure, which resides in the University of Illinois Observatory, is actually a photoelectric cell from the early 1900s and was part of the photoelectric photometer, an instrument that fit on the end of a telescope that measured the brightness of stars using electricity rather than visual comparisons. This light recording discovery is the distant predecessor to today’s solar panels and digital cameras.

“This,” Craig Sutter (ENG ’71), a longtime Observatory volunteer said, “is probably the most special object we have.”

The cell was part of the groundbreaking research by faculty members Joel Stebbins and Jakob Kunz in 1907 and 1911 that led to the University of Illinois Observatory’s National Historic Landmark designation in 1986. It was this research—as well as the building—that made the observatory one of only 2,500 registered landmarks in the country. (The university’s one other National Historic Landmark, the Morrow Plots, is located just to the south of the observatory.)

Michael Svec (LAS ’88), while a still an undergraduate student in physics, led the push for the formal recognition. He likens his success to serendipity.

“It was a story that hadn’t been told very well or often enough, and the timing just happened to work,” Svec said as he recalled his time spent obsessively researching the observatory’s past. Even though he is now a professor at Furman University in South Carolina, he published a paper about the observatory just earlier this year.

Stebbins left Illinois in 1922 to become the director of the Washburn Observatory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. While he took most, if not all, of the materials from the two decades he spent at Illinois as director of the observatory, a later agreement was reached that one of the few existing photoelectric cells from that period would remain on permanent loan to Illinois.

“If Mike Svec hadn’t gotten this on the register,” said Sutter, “I bet you even money that this building wouldn’t even be here right now.”

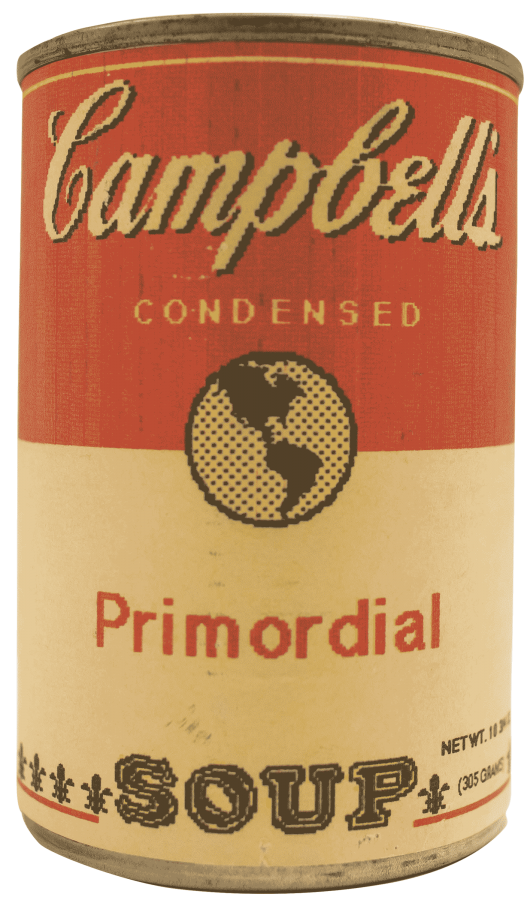

Painting the team blue

Painting the team blue

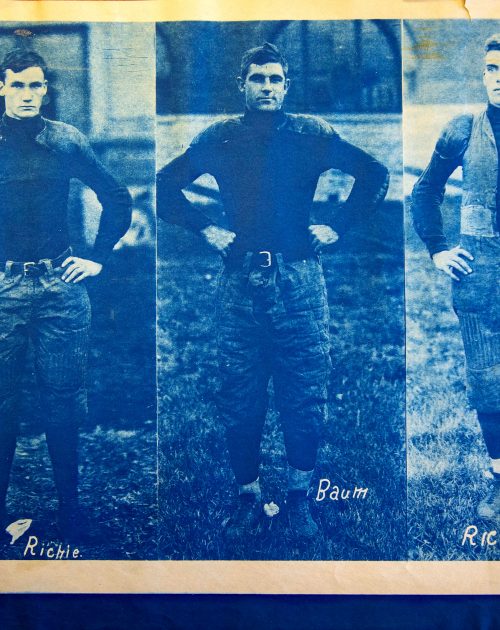

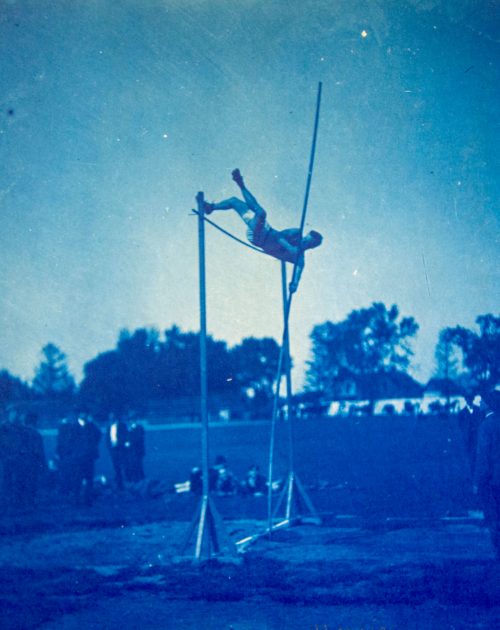

Illinois second baseman, G.F. Beyer, with a slight smile, hands on his hips, and a far-off gaze, stands in front of sagging pastoral backdrop, straw scattered at his feet. Beyer and his teammates were fortunate to be coached in 1907 by none other than the famed George Huff.

His photograph is one of many bright blue images of athletes tucked in a file in a box in the archives. This type of photographic print, known as a cyanotype, is created by painting light-sensitive iron salts onto paper, placing a camera’s negative on top, and then exposing it to a light source. A rinse in water “fixes” the image permanently on the paper.

This early method of making photographs dates back to first half of the eighteenth century and fell back into favor at the turn of the twentieth century. Architectural drawings—or what then became blueprints—and photography proofs were created using this process. And because cyanotypes were not usually considered a final photographic format, many of them were discarded, said Jennifer Teper, the university library’s head of Preservation Services and the Preservation and Conservation librarian.

In Illinois’ inventory, she estimates there “are certainly hundreds, maybe a few thousand. It wasn’t the most popular format.”

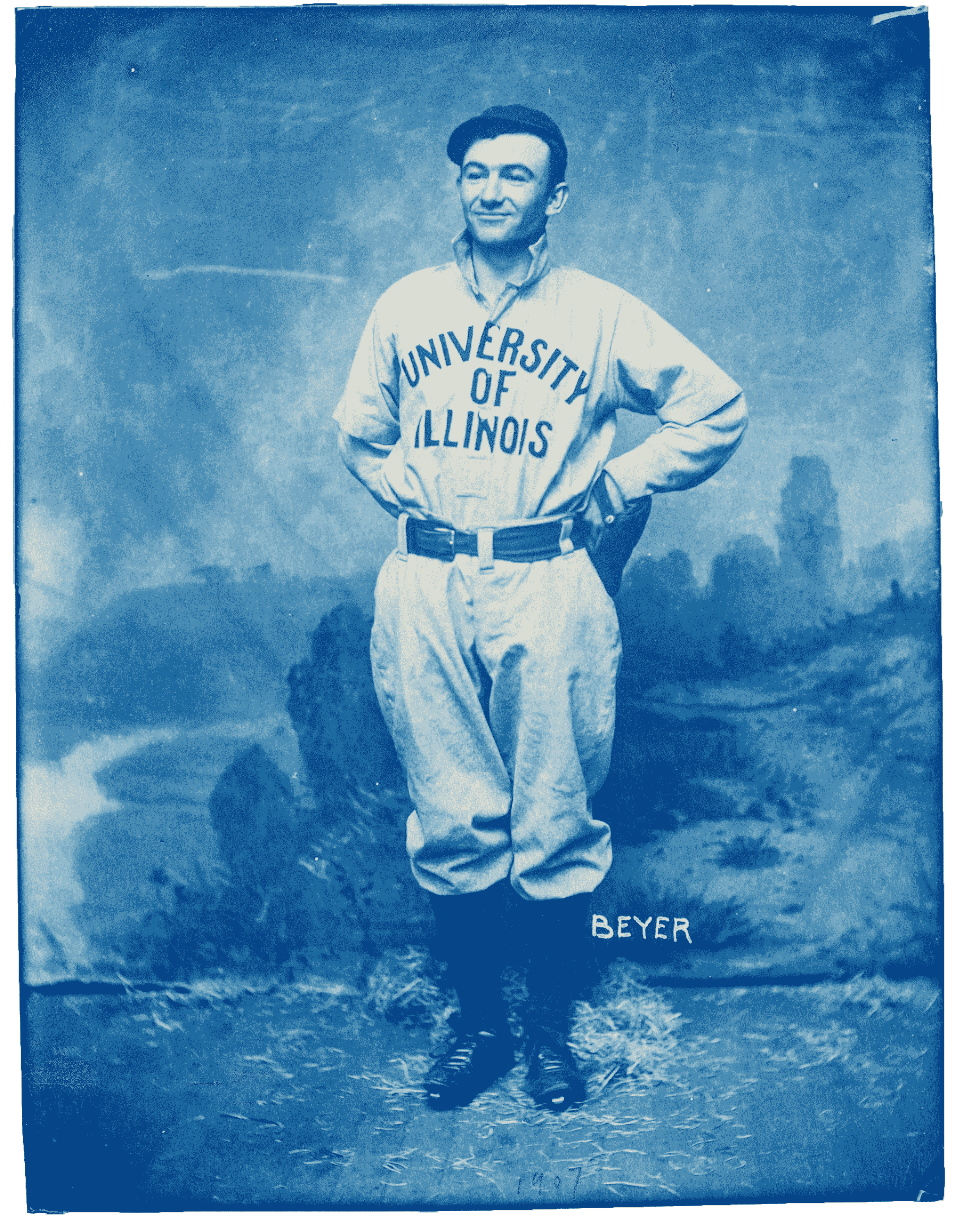

Bringing beauty to campus

Bringing beauty to campus

Andy Warhol’s, “Marilyn,” its vivid colors overlaid on a staid portrait of Marilyn Monroe—arguably one of the artist’s most iconic pieces—is considered a highlight of the Krannert Art Museum’s permanent collection.

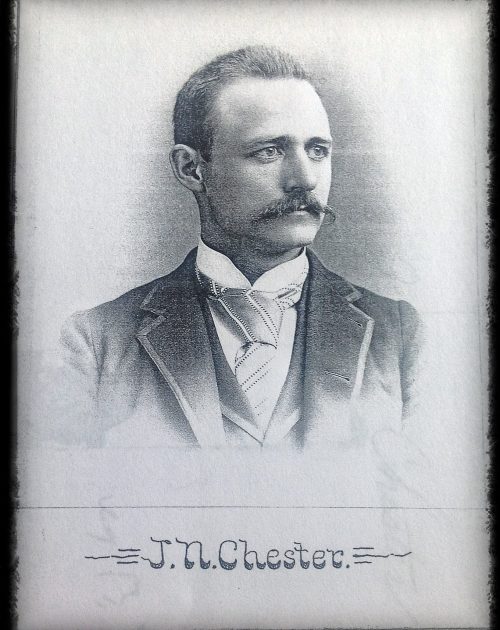

The 1971 print was an important addition when it was acquired in 1983, yet how the museum was able to purchase it is actually a story about university alumnus John N. Chester.

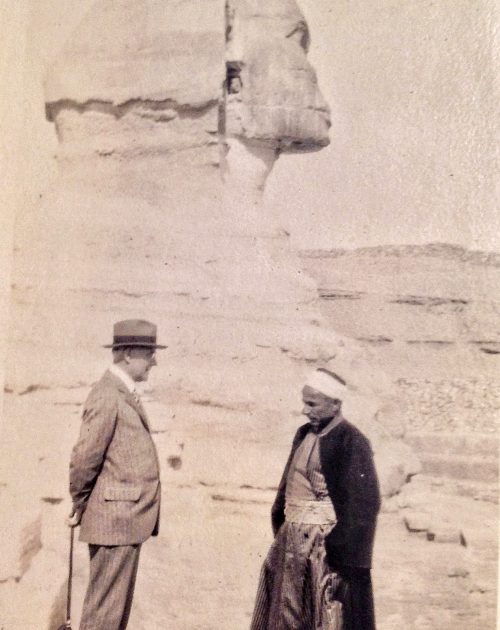

Shortly after Chester was born in 1864 near Columbus, Ohio, he moved with his family to the Champaign area. He graduated from the University of Illinois in 1891 with a degree in civil engineering followed by a master’s in 1909. Pittsburgh was where he established his professional career as successful water works engineer, but his love of collecting took him on trips around the world. On one trip, he and his cousin crossed paths with Charles A. Lindbergh and his wife Anne in northernmost Canada. The Lindberghs were completing a record-breaking flight through the Arctic.

The university never strayed far from his thoughts, however, and he often returned to Champaign. Chester served as both president of the alumni association and director of the University Foundation. Upon his death in 1955, he left an endowment to “My Alma,” as he affectionately called the university, meant to purchase pieces that “will add to the attractiveness to the university…such as rare books, works of art, and museum pieces.”

Jon L. Seydl, the director of Krannert Art Museum, believes the museum’s collection has grown in important ways as the result of this significant gift.

“What I find so fascinating is how curatorial and directorial priorities have changed over time and even the broad purpose of the museum,” said Seydl, “and you can see the evolution of the museum through requests to the fund over the years.”

Over the last almost forty years with the use of the John N. Chester Fund, the museum has been able to purchase 58 works created by dozens of artists, spanning five centuries.

This story was published .