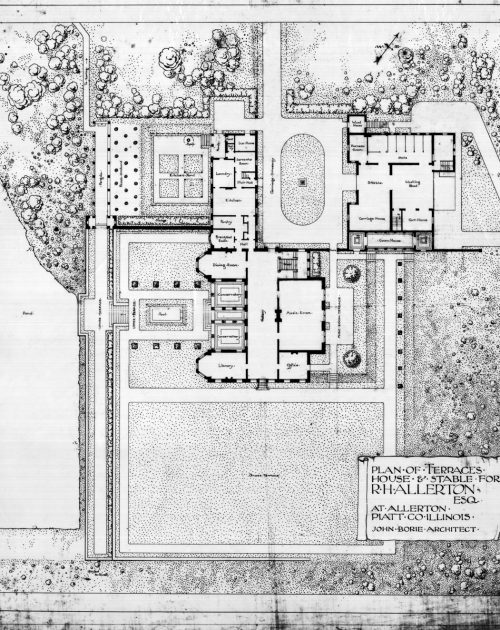

Few of us can imagine having enough money or resources to build the retreat of our dreams. Robert Allerton, however, was the son of one of the wealthiest men in Chicago, and in 1899, he broke ground on his dream on over eleven thousand acres outside Monticello, Illinois, called The Farms. It was a mansion in the style of Ham House, a seventeenth-century English manor with a sunken garden inspired by trips to Bali, stone pathways lined with sculptures, and elaborate gardens filled with roses, peonies, and tightly pruned hedges. Miles of hiking paths wound through the property.

Allerton’s roots didn’t begin on the prairie, however, but instead on Prairie Avenue, the tony Chicago street that was home to many of the city’s wealthiest families. His father, Samuel Waters Allerton, made millions in livestock, providing pork to the Union army during the Civil War and helping to organize Chicago’s famous stockyards. Many of the prominent businessmen and philanthropists of Chicago’s Gilded Age built their mansions along Prairie Avenue — men such as Marshall Field, George Pullman, and Daniel Burnham.

Unlike his business-minded father, Robert Allerton’s passion lay in art, an interest encouraged by his stepmother, Agnes. After being inspired by the paintings and sculpture he saw at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, he traveled to Europe to study art. While international travel was something Allerton would continue for the rest of his life, his life as an artist was short-lived. He quickly realized he was better suited to be a patron of the arts, and so, at his father’s direction, Allerton returned to Illinois in 1898 and moved downstate to manage The Farms.

While the farm was an important asset in the family’s portfolio, Allerton’s estate also became a haven for artists and a home for art from around the world. He began to build an impressive collection and held lavish parties to show off the works of art. Friends from Chicago — opera singers and ballerinas, politicians and millionaires — would take the train down to attend.

✦ ✦ ✦

In the early 1920s, Allerton began two of his life’s most fulfilling associations. He began donating works to the Art Institute of Chicago — his first gifts included pieces by Gauguin, Rodin, and Picasso. At nearly the same time, he met Illinois architecture student John Wyatt Gregg (GRAINGER ’26) at an event on campus, and the two remained companions until Allerton’s death. They traveled the world together, collected art together, and Gregg was responsible for much of the design on the Allerton Estate, including the famous Sunken Garden and the settings for the sculptures, The Death of the Last Centaur and The Sun Singer.

Allerton and Gregg remained deeply connected to Chicago and split their time between the estate and the city for many years. Allerton continued to support the Art Institute, serving as vice president until 1949. He ultimately donated over 6,500 works of art and funded the Agnes Allerton Gallery of Textiles. So influential was Allerton to the shaping of the Art Institute that in 1968, it officially renamed the original building (built in 1893 for the World’s Fair and now the main entrance) the Robert Allerton Building.

✦ ✦ ✦

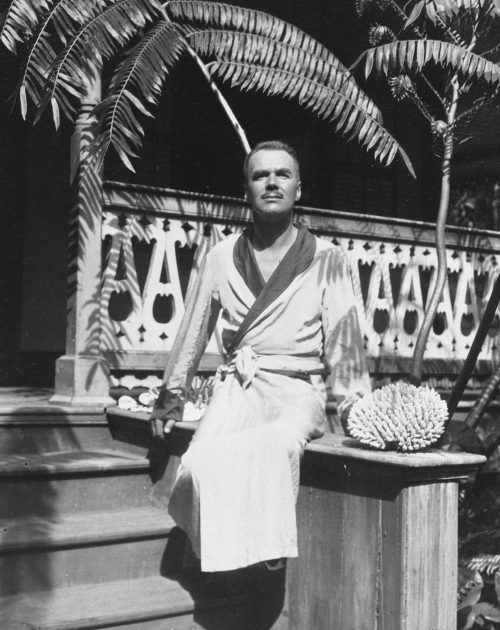

Cold Midwestern winters drove Allerton and Gregg to Hawaii in 1937, where they designed, built, and maintained another residence. They decided to live there year-round in the 1940s, and so gifted The Farms to the university to be used as a public park, retreat, educational center, and nature reserve. At the time, this gift to the university more than doubled the university’s land holdings. While Hawaii became their new home, they were careful to ensure that their employees in Monticello would continue to work, and the land would be preserved and cared for.

When Allerton passed away in 1964, his estate was valued at $21.5 million, equivalent to over $186 million today. He left bequests to numerous people and organizations, including the Art Institute in order to maintain the Allerton Wing. The rest of his fortune was left to Gregg, who continued to honor their incredible commitment to philanthropy until his death in 1986 when the rest of the fortune was distributed among several charitable causes.

Today, The Farms is known as Allerton Park & Retreat Center. The influence of Allerton and Gregg continues to be reflected in the beauty of the grounds, the art so carefully selected by the men, and the care that is taken to maintain this picturesque hideaway in the middle of the prairie.

This story was published .