The Illinois Storytellers series brings you first-person pieces from distinctive Illinois voices. We’re proud to launch the series with thoughts from Nick Offerman (BFA ’93). These remarks were originally given at Illinois’ May 2017 Commencement.

Good morning. I am sincerely humbled to be asked here today, and grateful for the opportunity to flap my gums at you for approximately the minimum amount of time you want to let your varnish oil and beeswax finish soak into the wood before wiping it off. I apologize for appearing before you without my moustache, but it had unfortunately been previously committed to an appearance at the Montana School of Forestry.

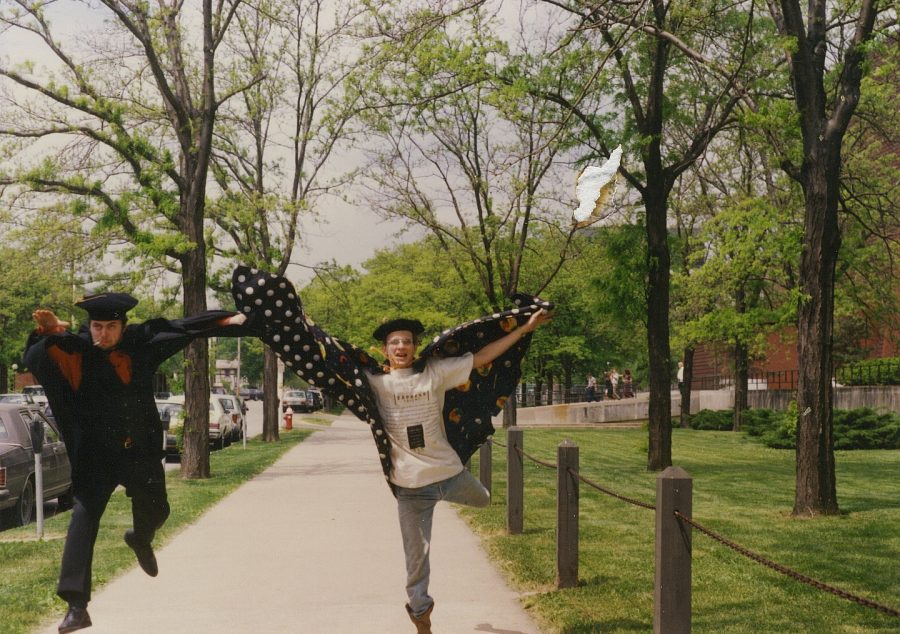

If we could all travel together back to 1993 and scrutinize the 23-year-old version of me that graduated from this very university with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, you might well be amazed at the bleary-eyed ragamuffin standing unsteadily before you. Although maybe not, since I ultimately found a successful career in the category of “goofy jackass” that has made some of you familiar with my methods, and for those of you who are, you know that I acquired whatever small fame I possess largely for consuming an impressive quantity of bacon and eggs. I could enumerate many other gems from my resume for you to establish my credentials but there’s likely nothing I can say to you today that will be half as inspiring as the fact that back in those salad days I endured two brief stints in the Urbana jail for some minor, ill-advised tomfoolery, and somehow still managed to be invited to speak to you here today. I look upon you now and I am moved, for you are as well-tasseled and bright a crop as these cornfields have witnessed, and that gives me hope.

Today we eject from this cozy nest of academia over 13,000 of you in 189 majors, who have come to this school from all over the country and even the world to ready yourselves for a fruitful career in the realm of adulthood. You have reached the glory of the finish line, and have undoubtedly done so with good old-fashioned hard work, with creativity, talent, stamina and probably for some of you, a not inconsiderable amount of beer. I feel you.

When I graduated, I remember living under the assumption that I had things pretty well all figured out; as though life had stuck a fork in me and pronounced me done. I was pretty cocky about it for 17 minutes or so, until cold, hard reality set in. I hope for the sake of your future meals, your degree today is not in theater, because we were not only hungry for jobs back then, we were also just plain starving. Turns out I had some schooling yet to endure.

I’d love to believe that what got me here to this microphone was my talent and my good looks, but unfortunately I own a mirror so I am disabused of that notion every Saturday night when I groom myself. Instead I have to give major credit to some very good advice from some very good teachers. Here is some good news for you. Your school work is done. However, your life’s work is only beginning. That’s actually the good news part, because if you play your cards right you will choose work for yourself that you love, which I know for a fact has not always been the case with class assignments. Your calling, once found, will continue to supply you with teachers, only these instructors will be more like those Jedi types who tell you the secret shortcuts to the end of video games. I am sorry to rely upon a reference so unseemly as video games, but I am trying to come across as relatable to you charismatic tadpoles.

My own first example of this comes from my best teacher here at the U of I, a wizardly Professor Emeritus by the name of Shozo Sato, although we call him sensei, which is Japanese for teacher. He came to this country from Japan in the late 1960’s a highly-trained artist in several disciplines of the zen arts, including Kabuki Theater which was the art form he taught me. Here is a man, an immigrant, one of the most multi-talented humans I have ever had the pleasure of encountering, who was dealt a very particular hand of cards.

After being much closer than comfort would prefer to the American bombing of Hiroshima at age 7, he and his father visited the leveled city a month later to witness the intense destruction and aftermath of the nuclear attack. All that remained of his father’s house were the granite entry pillars, scoured white by the blast. The deep impression this left upon him launched young Shozo upon a lifelong search for peace by way of the arts. He eventually moved to the states and ended up here in the cornfields of Champaign-Urbana where over the years he has influenced thousands of students and their families by means of an entire menu of classes in the Japanese arts. When I think about the desolation of the unreal, bombed landscape witnessed by Sato-sensei, and the life he chose partly based upon that observation, he seems to me like one of the first bright blossoms that managed to stubbornly poke up through the bleak rubble of a war zone to remind us that beauty and light are also possible.

As great teachers do, he curated his life – he tended his garden both literally and figuratively in a way that the produce of his own life and labor became the tomatoes and the sweet corn by which we his students were nourished, while he also taught us to garden for ourselves, even as he gave us the seeds with which to start. I wield a whole pouch full of these poetic tulip bulbs in the form of zen philosophy, but here is the one I love the most. This is going to sound like a peculiar thing to say to a group of 13,000 graduates on the very day that you are finally, officially done attending classes, but the advice is quite simply to “maintain the attitude of a student.”

We’re all human beings, which means we’re all flawed by definition. The realization of this truth is a great baseline for the music of your life’s pursuit, whether that’s a straightforward Sousa march or the most licentious reefer-fueled jazz. Every day is another opportunity for learning, for improvement. If you mistakenly think you have finished learning, because you have mastered your craft, or just turned in all of your term papers, then you open the door for bitterness to take hold. Instead, you want to cultivate an openness to the world, to start the daily good work of being alive with the presumption that you need to learn things, not teach them. You need to start your conversations with a welcoming stance of anticipation, not a defensive crouch. Assume the person you’re speaking with knows something you don’t, and be eager to learn it.

By maintaining the attitude of a student, you afford yourself the opportunity to consistently improve your situation, and that of your loved ones, for the rest of your days. You can become better at your job, or hugging your family, or gardening, or speaking Spanish, or driving defensively, or grilling delicious ribeye steaks, or all of the above. If today you cannot apprehend how these improvements will layer glory and satisfaction into your daily practice, then your apprehension is also something you can improve.

The most obvious obstacle to trying in life, to stepping up to the plate and taking a swing at the fastball, and then the curveball, and then the dirty slider, and so on; the main hurdle to overcome even should you have the courage to bunt, or take the pitch, or employ a run-on sports metaphor in a commencement address is simply this: fear.

Which brings me to the other best teacher whose influence upon my time here can only be described as formidable. His name is Dr. Robin McFarquhar, PhD, and he used to teach movement and mask work in the theater department which doesn’t go very far towards accurately describing his contribution. Those phrases call to my mind images of black turtlenecks and interpretive dance, both of which we indulged in, make no mistake, but it would be more evocative and accurate to say this of Dr. McFarquhar – he taught me to fight with a sword. Or swords. Namely, court sword, sabre, rapier and dagger, katana, and the one and two-handed broadsword, not to mention the quarterstaff and of course, hand-to-hand.

Picture if you will, Mel Gibson in Braveheart, and then look slightly to the left and behind him to spot his decisively more intelligent but no less tenacious little brother. Scrappy as hell, but he also keeps the books for the clan. A fun fact, for further context: Robin actually auditioned for the role of Gandalf, but they said he looked “too wizened.”

He grew up in the clammy, grey embrace of Dickensian poverty in London’s East End, the first in his family to attend college, and was an exceptional pole vaulter who saw his Olympic dreams dashed by a back injury. This led him to a study of sports medicine, which brought him right here to Champaign-Urbana, by covered wagon no less, which must have been hell on his back, to pursue a Master’s degree in Kinesiology, which he followed up with a PhD which I’m given to understand is a yet even more prestigious degree. After a couple of slight contortions he found himself on the faculty of the theater department where he has been changing lives for 34 years, and he is now officially the Chair of the acting department. Another immigrant. He has also worked as a professional fight choreographer all over the country, teaching thrusts and parries to the likes of Mark Ruffalo, Denzel Washington and myself: the big three.

Here’s the thing. Robin was the kind of progressive teacher who does a hell of a job teaching his or her subject, sure, but he didn’t stop there. With every student in every class, he discerned every way that he could see to teach them not only sword fighting and juggling and such, but he also taught courage. Under his guidance we were invited to take a good honest look at ourselves and instead of seeing the deficits that were constantly being pointed out by popular culture, advertising and fashion, not to mention acrimonious siblings, he suggested that we instead recognize the exceptional value of the unique and magical human animals that we were and the beautiful souls therein; we were encouraged to recognize each our weird, individual flames and what it was that fueled that fire, an introspection which I would now in turn invite you all to sample.

Lean over for just a moment if you will into some Fine and Applied Arts and think about what it is you hope to do in your lives and how your time here has prepared you to do that or not. There are a lot of safe choices that you can make, and that’s fine, perhaps you’ll end up complacent at best, but there are scarier, harder choices that once faced down might yield you more substantial happiness and therefore far greater success. Not success as determined by your bank account or the fancy car in which you can cruise the strip on Saturday night but by the thrilling of your hearts and by the smiles on the faces of your loved ones, and by the warm fellowship of your neighbors and your community. I can tell you with some confidence that the easy way is very seldom the right way. Robin taught me to have the guts to recognize and subsequently value my idiosyncrasies and learn to exploit them to my advantage rather than shy away from them. I talk too slow, and I can eat a lot of breakfast food. That’s my bag, and it’s going great.

Which brings me to now focus upon one of our most valuable but under-celebrated attributes: our flaws and the resultant mistakes they can cause us to make. And also my next teacher, a farmer and writer who lives in Kentucky and has more common horse sense in his left work boot than I could ever aspire to. His name is Wendell Berry. I found him through reading his books of my own volition, which is something I encourage you to keep doing in the years to come, even though they have not been assigned. Tell you what, I am making you this assignment right now. And it doesn’t have to be actual books, I just entreat you to browse in the great public library of life, make your choices, and consume them with gusto. You choose the medium – if not books, then people or leaves or sausages or buildings, or a sampler plate, dealer’s choice, but believe me when I tell you that what matters is that you make your selections. Don’t let apathy get a hold of your ankles and drag you down to a life in the pub, for that way lies depression. Or so I have read. Ahem.

Wendell Berry wrote “It may be that when we no longer know what to do, we have come to our real work and when we no longer know which way to go, we have begun our real journey. The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.” One of the most important misconceptions purveyed by our modern consumerist society is the ignominy contained within the social media phenomenon known as the “epic fail.” However, I would argue that if you’re not making mistakes then you’re not living. And if this is true, the only fails worth a damn are the ones that are the most epic. I’m not suggesting you should all try hang gliding off the student union, or take a skinny dip in the Sangamon River in February or something. I’m just saying that big swings are often worth taking. You shouldn’t let the threat of a big miss stop you from taking them. The misses may be more worth it than the hits, in fact. If you would hope to wring the full possible flavor out of your life’s journey, then you had best pick some challenges and get started. But enough philosophical twaddle, it’s high time we swing the focus back to woodworking.

When you set out to build, let’s say a walnut dining table, you sketch up your design, if you’re intrepid, or if you’re wise you choose some plans published by an accomplished woodworker who already went ahead and solved a lot of the mistakes before you. Once you have your design, you need to acquire your materials, and at this juncture the sagacious woodworker immediately assumes that he or she is going to make some mistakes, which means that if the design calls for 4 planks of walnut, then you purchase 6 planks. Even if you’re experienced at life, I mean woodworking, and less prone to making amateurish errors, over the years you have come to understand that sometimes all of your planning and foresight can be, however flawless, immediately undermined by mother nature when she for example hides a weak pocket of bark right inside that board that looked like it would become 2 perfect table legs, but when you slice it open to reveal the pernicious anomaly, the once valuable plank is reduced to kindling and you are reduced to tears. So, to foresee and then prevent such traumas, you buy a couple extra boards. Afford yourself the time and materials to make mistakes, and your walnut tables will prosper every time.

Woodworking, and really all the fine arts, are a great analogy for life itself, because you quickly come to understand that your work can never be perfect no matter for how long you sand it. Whether you are crafting a symphony or a novel, or a 3-legged stool, or a marketing report, a non-profit organization, or a park by the river, all you can do is keep editing and improving it until it’s due. Then you turn it in, you walk away, you digest the effect of your work, whatever that entails, you learn what you can improve in your next attempt and you get back to the grindstone with your nose, to make a figure of speech.

“The impeded stream is the one that sings.” Mr. Berry is admonishing us to choose the path less traveled. Modern conveniences excel at providing us with nefariously easy choices and they grow easier with each passing year. Their sellers are correctly betting on our human tendency to make the lazy choice, to take the impediments out of our streams, thereby curtailing our songs. We’ll never be free of our human nature and so we must remain ever vigilant to fight the allure of physical and moral softness. When we have finished a delicious milkshake, the easiest thing to do is throw the cup and straw in the grass, but we have learned the value of seeing that rubbish safely relegated to an appropriate receptacle. It takes a little more work, but it is well worth our collective enjoyment of sidewalks and parks free of trash. I encourage you to refrain from littering the fields of your own experience. Instead, you might try cultivating some rosemary in them. It’s delicious, and packed with Vitamin D.

Healthy cooking brings us to the final teacher in my long speech, and this person is actually a very cute couple, my mom and dad. I know it’s pretty cliché to bring up your mom and dad upon such a nostalgic and toney occasion as this, but I have never claimed to be anything but pedestrian in my thinking. In fact, I believe one could say that it is my jam.

I have to tell you, I’ve met a lot of beautiful and rich and famous people, and that was just while visiting the set of Sesame Street. We matriculate through life discerning who is talented or not in all walks and categories, and we see those standouts rewarded for their prowess each in his or her own way, and we come to believe that such rewards are the treasures worth seeking. Money. Fame. Trophies. But I have to say that I have been the most viscerally moved not by Lady Gaga firing off a barrage of her astonishing arpeggios, or Stephen Curry making our heads spin with his 3-point shooting. No, what makes me stand up and say howdy is when I see somebody get up off of his or her ass and help out another person. Because the greatest and much more readily available treasure we can and should pay one another is respect.

This is pretty much all my Mom and Dad do when they’re not dancing a rousing polka or playing euchre. They are not capering clowns, so I wasn’t receiving a lot of guidance from them as regarded my own particular life path, but their gentle and consistent tutelage, of a more profound and benevolent nature, still took root. They told me and my siblings to tell the truth; to treat every other person with the best manners that we could muster, and to work hard. “If you’re going to do a job, do it right” was our household motto, and after I tried out some custom alternatives to their guidelines, like for example “don’t tell the truth,” just to be sure they had me on the right tack, I realized the beautiful value in their lessons and I strapped in. I may not know much about a lot of things, like fashion, or man-scaping, but I can tell you this with the authority of my 46 years of labor: I have never seen anybody who was mean or discriminatory or superior receive anything but unhappiness as a result of their behavior, and I’ve never seen anybody who had good manners and equitable treatment for his or her fellow humans that didn’t make a whole passel of people happy. “It all turns on affection.” That’s Wendell Berry again and I know I’m mixing my teachers now but just sit down, we’re almost home. I want you to think about that. The main thing that has driven my teachers and yours to apply themselves to their benevolent work has been affection. It certainly hasn’t been the paycheck. Affection. For other people and the good works they might in turn undertake, and for the works of nature. Wendell Berry again, wrote “Whether we and our politicians know it or not, nature is party to all our deals and decisions, and she has more votes, a longer memory, and a sterner sense of justice than we do.”

Leslie Knope once said that Teddy Roosevelt once said, “Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is a chance to work hard at work worth doing.” Well, what does that mean? For that matter, what is behind all of these nuggets of advice I am imparting today? Ladies and gentlemen, the answer is, as it has always been: love. All of these sign posts I’ve erected for you as we stand briefly together upon your day at the crossroads, signs made probably out of a wood that is appropriate for exterior use – teak if I can find it, but more likely Cedar or Osage Orange, these signs just add up to a common goal. To love and be loved. Many great writers have elaborated upon this chestnut, but assuming you’ve heard enough of Dickens and the Beatles, today I will share with you some lyrics from the great Tom Waits: “Well the moon is broken, and the sky is cracked. Come on up to the House. The only thing that you can see is all that you lack, Come on up to the House. All your cryin’ don’t do no good, Come on up to the house. Come down off the cross we can use the wood, Come on up to the house.” That song always gets me because all of my teachers have really just been telling me the whole time to come on up to the house. We’re all in this together. Get yourself a seat. Can I get you a beer? Is everything ok? That is what I think of when I think of working hard at work worth doing. That’s the recompense. Do you have clean water? Are your kids safe? What can we do for you? Yes I have beer. If that’s not love, and if that’s not good work, I’ll eat my hat.

Here’s more good news. You can always be looking for teachers. Surround yourselves with teachers – smart people, funny people, interesting people who come from different places and have seen different things. You’ve just spent four years surrounded by actual teachers, sure, but also peers and lovers and classmates who taught you through friendship, or osmosis, or trial and error. You are not done with teachers, when you leave this campus. If you’re lucky, you will be surrounded by teachers for the rest of your life. I got one of the foxiest and smartest teachers I ever met to marry me. Try that one out if you can pull it off. Highly recommended. If you give and receive love, and make some mistakes of course; if you can find good work to do and get to doing it; if you can maintain the attitude of a student, then you stand a good chance of becoming such a teacher yourself.

13,073 of you are earning your degrees today. I literally can’t even imagine what you will achieve because, for one thing, I am very dumb at chemistry. You will feed us and heal us and clothe us and advance and delight us in so many ways. You will legislate the slag back out of our streams. You will also sweep floors and drive buses and shingle roofs and teach kids to ride bikes and use a dovetail chisel, and you will know that those occupations are as imperative as the rest. And sure there will be a few duds among you, that can’t be helped. I’ve been a dud at times, and I can assure you that it doesn’t last–it gets better. If things do seem hopeless, find a teacher and then maybe you can become that one bright blossom poking up defiantly through the rubble. We need all of us to pitch in if this is going to work, this love thing. Take these expensive, hard-won degrees and use them to administer affection to the rest of us, and teach us.

And so the time has come to wipe the excess varnish from our walnut table and don’t forget to properly dispose of your oily rags. With the exception of Wendell Berry, all of my aforementioned teachers are here with us today, and so as I congratulate you on your magnificent achievement, I will ask you to make a noise of gratitude in their direction as well, as I sincerely and finally pronounce: bully for you.

This story was published .