A small, solitary, glass Buddha sits on a wooden table by the kitchen window. The figure occupies the spot where Shozo Sato’s late wife of forty-five years, Alice, used to sit and look out at the pond behind their house, watching neighbors fish from its shorelines or walk their dogs around its perimeter.

“We chose this house because it doesn’t look like I’m in the middle of a cornfield,” Sato said, smiling. “You know, that’s what I’m always trying to escape.”

Artwork—his own and others—fills the first floor of his house, and the smell of burned incense hangs in the air. Nearby, a fabric panel obscures a wine bar where Sato performs his renowned tea ceremonies.

The couple moved back to Champaign in 2016 after spending twenty-four years in Northern California. The move out West, prompted by Sato’s retirement in 1992, was made possible in part by Sato’s friend and former student, actor Nick Offerman (FAA ’93). But the allure of the simple university community life they once lived when Sato was a professor of art and design in the College of Fine and Applied Arts beckoned.

And so, the dramatic Pacific Ocean was replaced with the calm waters of a manmade pond. At ninety, Sato is still creating art.

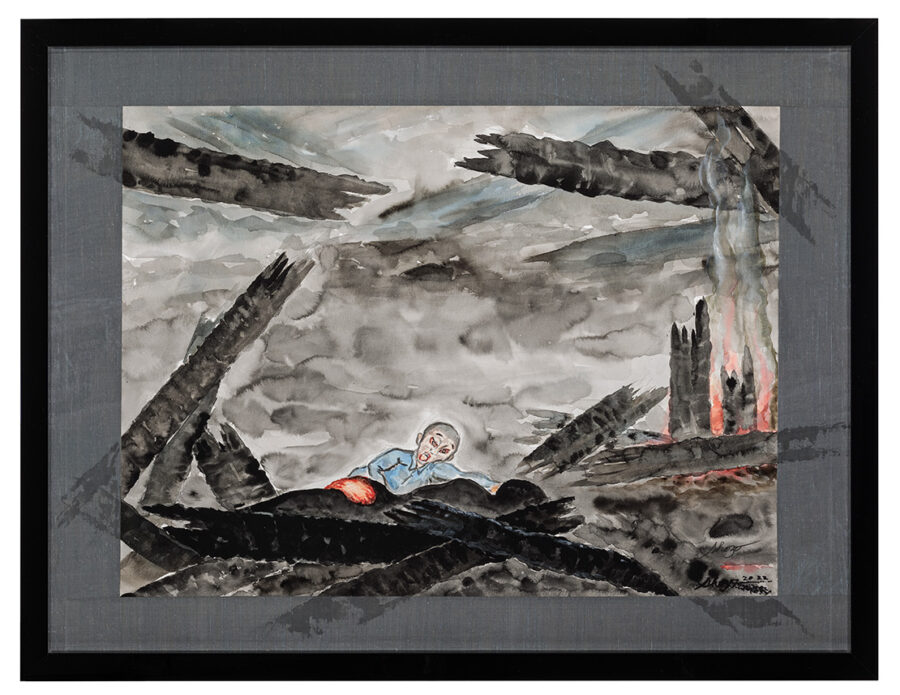

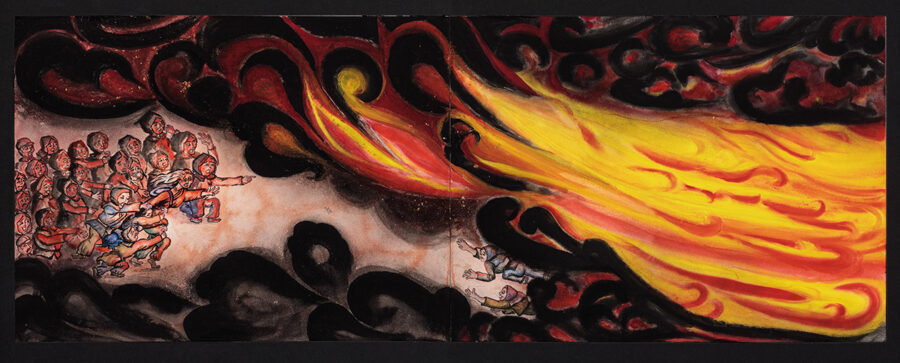

Over the past few years, since Alice passed away, his creative attention has turned to his childhood in World War II Japan. Like a tide at the mercy of the moon, a sense of urgency weighs on Sato to share the horrors of war. “Not too many people remember anymore, or they aren’t alive,” Sato shared recently. “I should leave this memory for the next generation.”

PERSEVERANCE

PERSEVERANCE

In 1964, thirty-one-yearl-old Sato arrived at Illinois as a visiting artist. The energetic musician, performer, and actor educated in Japan introduced the Japanese aesthetic to the university in a profound way with the founding of the first Japan House on California Avenue. He graciously shared tea ceremonies, kabuki performances, and calligraphy instruction with a campus eager to learn.

He also brought with him the disciplined, creative mind of a survivor who, just nineteen years earlier, when he was eleven, watched his hometown set ablaze in the waning days of World War II. Two-hundred-and-seventy-four U.S. B-29 bombers rained down incendiaries on Osaka in the middle of the night of March 13, 1945. That was the first of eight bombings that resulted in ten thousand deaths and the destruction of the second-largest city in Japan at the time.

Sato’s family in Osaka was spared, but the same could not be said of his father’s relatives. They all perished August 6, 1945, in Hiroshima, when the United States dropped the first atomic bomb.

Miraculously, Sato didn’t harbor anger or resentment against Americans. In fact, quite the opposite.

“You know, it’s strange. After the war, we were occupied by American forces, and when we saw young GIs, we loved them—kids loved them. They were clean looking, nice, and kind,” Sato said when he recalled meeting Americans for the first time. “When politics are involved, people get angry. That’s the major difference.”

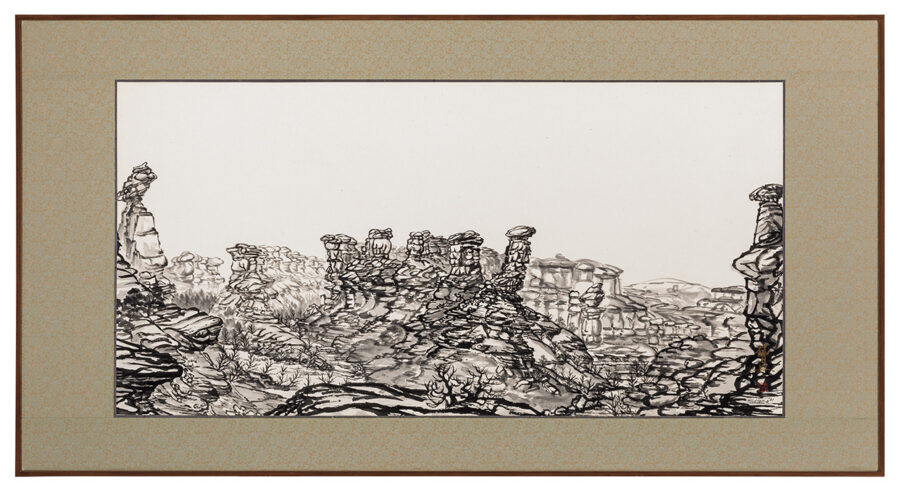

Sato’s move to the United States gave him the opportunity to explore unfamiliar yet captivating landscapes. He was especially inspired by the American West, and, in 1984, spent his sabbatical traveling in a van that he outfitted with a bed and desk. From these travels, he created paintings, including A Thousand Towers, which captures rock formations in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park and Mountain Cascades, depicting the flow of water through the rocky terrain of the Wild Basin region of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Back at Illinois, Sato focused on using his art to enhance communication between the two cultures he loved, building a community that thrived on learning and exchanging knowledge. Years fell away as he industriously created spaces for students—and the larger community—to learn about the culture that shaped him.

“I taught kabuki at the Krannert Center, choreography, black ink paintings, ikebana (flower arranging), and tea ceremony,” Sato said. “I was busy, busy, busy.” Then, at forty years old and in the throes of a demanding career, he received a welcomed interruption from a young woman in Colorado.

LOVE

LOVE

Alice Yoshiko Ogura Sato was born in 1926 in Antonito, Colorado, to Japanese immigrant farmers. She grew up surrounded by other newly immigrated and first-generation Japanese Americans drawn to the area by the promise of work.

In 1945, as Sato was witnessing an unthinkable tragedy in Japan, Alice’s stateside experience was comparatively fortunate. President Franklin Roosevelt mandated that Japanese, as well as Japanese Americans, living in the United States relocate to internment camps. Colorado Governor Ralph Lawrence Carr, however, refused to comply, and Alice and her family were able to stay at home. Governor Carr, on a limited basis, even welcomed those destined for the camps to Colorado.

Wartime emotions ran high throughout the United States, and, no doubt, racial slurs were hurled, but considering the treacherous conditions of other Japanese and Japanese Americans living in the United States, Alice and her family rode out the war relatively safely.

After the war, she became an award-winning biology teacher and was one of the founding members of the seven-hundred-acre Balarat Outdoor Education near Denver focused on environmental studies for school-aged students. In the 1970s, Alice and Sato’s paths would finally cross after being set up on a date by a mutual friend. They married in 1975, thirty years after the end of World War II.

LEGACY

LEGACY

Together, Alice and Sato were two sides of the same coin—their experiences of the war and how it shaped their childhoods were different, but they shared a core passion for teaching, art, peace, and a deep reverence for the power and beauty of nature. Both of them adopted Illinois as home, and Alice was a champion of what Sato was trying to accomplish here.

In 2004, several years after he retired, Sato was awarded the prestigious Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure, which recognizes longtime cultural and public service. “That was the biggest highlight of her life,” Sato said as he recalled Alice spending a week shopping for the proper dress. It was a magical moment for Sato and his American-born wife as they were received by the emperor of Japan and toured the Tokyo Imperial Palace.

Sato has built an enduring legacy on campus, most visibly through Japan House, the gorgeous building now located just off Lincoln Avenue, surrounded by Japanese gardens and a beautiful walkway lined with cherry trees that curves around a peaceful pond. Here, the vision he brought to campus so long ago extends to public programming for the community, university classes open to all students, and a formal minor in Japanese Aesthetics.

Alice’s family has left its mark as well. Upon his passing, Alice’s brother George left $2 million to help fund the Ogura-Sato Annex, an addition that will house new classrooms, a professional kitchen, and a fully accessible tearoom. Now, as then, Sato is still driven by what he sees as his purpose. “I never stopped teaching,” he said. “It’s the job of a lifetime.”

MUSHIN

MUSHIN

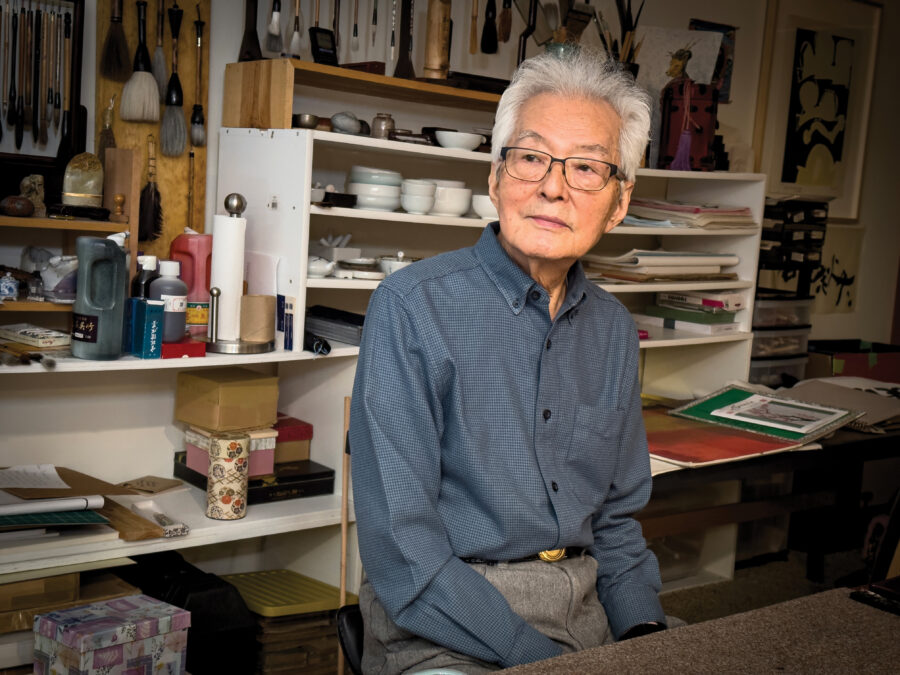

In the basement studio of his home, Sato teaches free calligraphy classes. Dozens of brushes of varying widths and lengths hang on the wall; white dishes for ink line the shelves; his art is displayed throughout. For several hours, he serves as a guide to his students as they practice writing an ideogram, or Chinese character, at one of the tables set up in the room.

“They concentrate their mind on their brush movement and the composition with the ideogram,” Sato explained. “By doing so, eventually you reach the state of mushin; your mind becomes purely empty, just a creative force.”

An endeavor even Sato finds difficult to achieve at times. In his own work, Sato is moving back in time to the experiences he had as a child witnessing the worst humans can do to one another. At ninety, he embodies both the young child feeling the heat of the fires and the man who, nearly eighty years later, is looking back through a longer lens.

“After you find yourself at the bottom, you have to look for happiness and beauty,” Sato said. “You need it. Otherwise, it was just a passing experience, people never learn from it. So, what will that experience be to you? It is the food for your soul tomorrow, and then happiness will find you.”

Sato is still sharp, but the memories he wants to depict feel out of reach when surrounded by everyday demands and responsibilities. For him to reach mushin, he retreats to a seaside hotel in Hawai’i.

There, he is a child standing on a mountainside watching incendiary bombs rain down, red lines crisscrossing the sky like fireworks. Within minutes, the entire city of Osaka is in flames.

This is the next painting.

This story was published .