We are biologists—entomologists to be exact—who have made it part of our lifelong objective to photographically document the natural world. Over the past forty-plus years, we have amassed an impressive collection of almost a half-million images taken in Illinois, the United States, and, during the past several years, the world. We have photographed in most areas of North America and explored some of the most biologically diverse areas on Earth—Manu National Park in Peru, the cloud forests of Ecuador, southern Africa and the horn of the Okavango Delta, the Falkland Islands, the Pantanal wetlands of Brazil, and northwestern Australia.

We are not photographic trophy hunters, seeking to make each and every image that perfect portrait, but biologists who seek to capture the little windows of time that show nature as it is.

✦ ✦ ✦

I still carry a three-by-five-inch notebook wherever I go and consider my collection of more than one hundred of them as one of my most valuable possessions. Here reside the notes and observations of everywhere we have traveled, locally, regionally, or globally. Some pages are warped and faded from rainstorms or hail events on the back on one notebook is taped a penguin feather, tracked in after a day spent roaming an island in the Falklands—just the penguins and us. Others are sweat-stained from birding adventures in tropical rain forests. When someone asks how I am inspired to write, I paraphrase poet Mary Oliver. My three-by-five-inch notebooks “are the pages upon which I begin.” – Susan L. Post

From the age of five or six, I was basically allowed to roam free. When my mother would say, “Go and play, but be back in time for lunch [or supper],” she had no idea what kind of “play” and license to roam she had unwittingly endorsed. Her only remonstrance was the inevitable, “Don’t go near the river; it’s too dangerous!” Of course, that just made the river more enticing. Often when I returned home covered in mud and reeking of decaying fish from a day spent exploring the flotsam, jetsam, and other treasures along this massive stream, she would inquire, “Have you been down to that river?” My answer was always, “Nope, just down to the spillway.” “Okay, then get cleaned up for dinner.” The fact that she had never been to the spillway and had no idea that it was a short stream immediately adjacent to the river served only to rationalize my little white lie. – Michael R. Jeffords

The popular phrase Be prepared is now second nature to us, both as field biologists and as nature photographers. Lacking preparedness in those disciplines can lead to missing crucial data points for a research project or failing to photograph that “decisive moment.” Nature is incredibly diverse and seldom predictable. In nature photography, when we go afield, seeking to document both the common and the bizarre, we make decisions beforehand that can determine our “preparedness”—for example, what equipment to lug along. – Michael R. Jeffords and Susan L. Post

When we travel, hike, explore, or even do fieldwork, we have goals and usually know what to expect. Yet our best experiences have been the unexpected—the surprises. While I have my lists and homemade field guide of what we expect to see…it is the surprises I am most excited about. As Dylan Thomas wrote, “When I experience anything, I experience it as a thing and as a word at the same time, both equally amazing.” Our travels are like that. – Susan L. Post

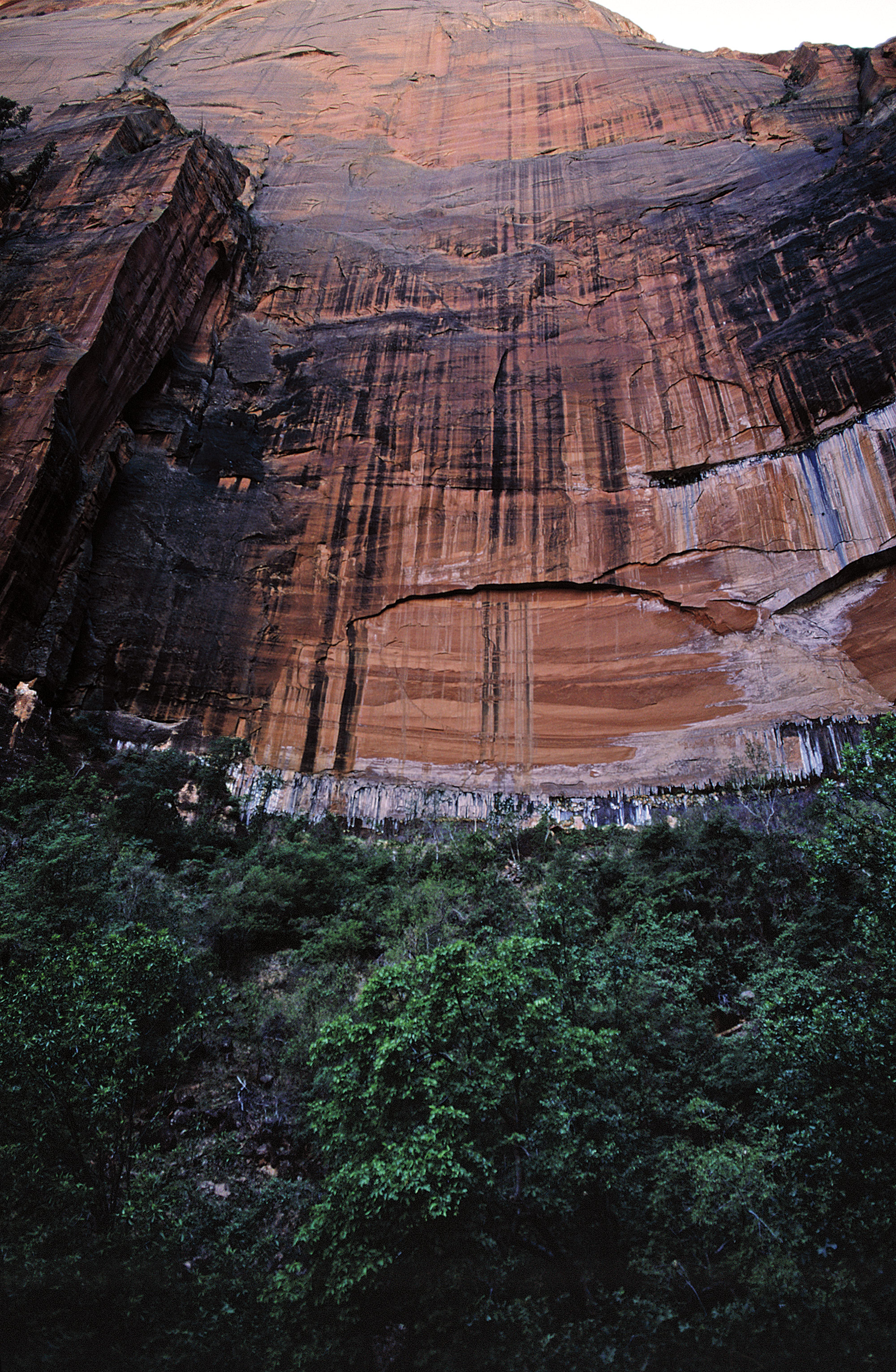

Only a few things can evoke universal silence from a crowd of humans—a funeral procession, a grand cathedral, or a classroom of children suddenly under the glare of an angry teacher. On a trip to Zion National Park, we experienced another. A trail led to a series of three emerald pools, each encountered sequentially as we stair-stepped our way up a steep-walled sandstone canyon. Emerald Pool #3 came into view, but it’s not the pool, per se, that stuns everyone into silence, but the setting. The modest oblong pool is lorded over by vertical sandstone walls of immense proportions, rising at least a thousand skyward feet on three sides. The walls are stained with centuries of dissolved minerals, creating a virtual kaleidoscope of color. While we were there, the only words spoken by the dozens of people were, “I feel so small.” – Michael R. Jeffords

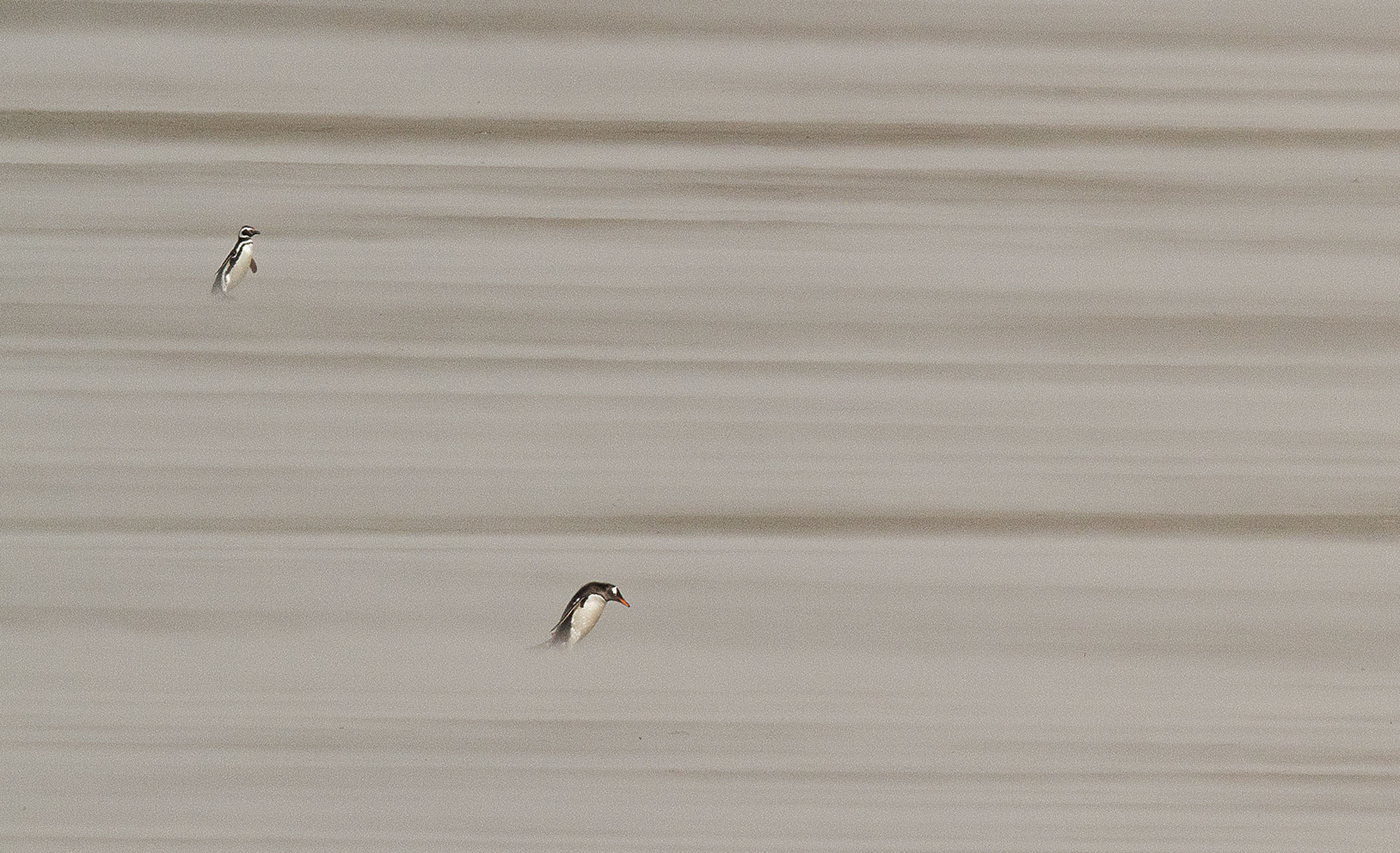

Some words just don’t seem to belong together: sandstorm and penguins certainly fit the bill. Even so, on a visit to the remote Falkland Islands, I witnessed a unique pairing of the duo. On the day we visited, we endured extreme weather that included sleet, rain, sporadic snow, even sunshine, but all modified (and made unpleasant) by sustained fifty-mile-an-hour winds! Even though the sand had been soaked by rain earlier that day, the fierce winds were blowing it across the beach in long skeins only a few feet above the surface—about penguin height. Because the blowing sand obscured their feet, the penguins appeared to float across the expanse of beach. Those that did stop to rest were soon drifted over and became mere sandy lumps. – Michael R. Jeffords

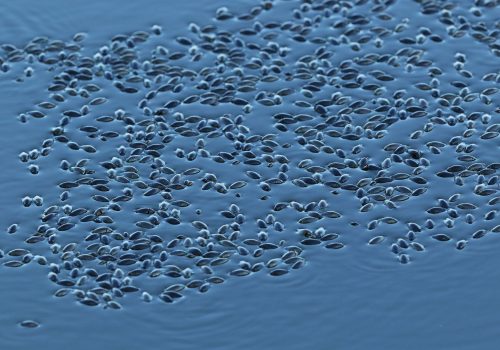

For those of us who collect, or have collected, insects, a prize from the New World tropics is the peanut-headed bug (order Hemiptera, family Fulgoridae). This is a unique relative of the cicada. We were visiting an area of northwestern Ecuador…at a small hotel on the edge of San Lorenzo. By North American standards, it would have received less than stellar ratings (maybe one or two stars). For three entomologists, however, the place was literally a paradise. After each long day in the hot, humid environs of the rain forest, we would spend the evening by the pool, sipping chilled Fanta and diligently watching the quiet blue-green surface of the water. Why? Because it functioned as an Olympic-pool-size pan trap for insects! The prize of the trip was when Joe, our colleague on the trip, found a large peanut-headed bug swimming about early one morning. Here it was, the treasure of my youthful insect collection, alive and colored in all its entomological splendor. Transport of our insect trophy into a nearby rain-forest habitat gave us endless opportunities to photograph our treasure in its primary habitat.– Michael R. Jeffords

✦ ✦ ✦

Michael R. Jeffords is the retired education/outreach director for the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS) and was staff photographer for The Illinois Steward magazine. Susan L. Post is a retired INHS field biologist and staff writer for The Illinois Steward magazine, and author of Hiking Illinois. They are coauthors of Curious Encounters with the Natural World, Exploring Nature in Illinois and the upcoming Butterflies of Illinois.

Text used with permission of the University of Illinois Press. Copyright © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Photographs used by permission of Michael R. Jeffords and Susan L. Post.

This story was published .