A robot named Stretch moved in with the Evans family for a couple of weeks in the summer of 2021. The robot may not be the friendliest-looking thing you’ve ever seen, but that may not matter when it comes to what it can do. It has a telescopic arm that extends from its middle. A two-fingered gripping hand sits on the end. There’s a video camera at the top and a mobile base that lets it move around.

On its visit, Stretch didn’t vacuum the floors like a Roomba; it didn’t discuss the weather or remind the Evanses where their keys were, as Siri might. But Stretch took on a host of tasks that made the Evans’ household better.

Before we hear what Stretch was up to, though, let’s meet Henry Evans.

Speaking at a TEDx conference a few years ago via a telepresence robot and a voice synthesizer, Evans told the crowd that he had lived “his version of the American dream.” Married to his high-school sweetheart. Two kids. A job as a Silicon Valley CFO. And a new house—a fixer-upper—with a beautiful view. Then, on August 29, 2002, after experiencing something akin to a stroke in his brain stem, he became a “mute quadriplegic at the ripe old age of 40.”

It took a few years, a very supportive family, and a ton of effort, but Evans is now one of the nation’s leading advocates and experts on how robots can help people who have severe disabilities. Leading a nonprofit called Robots for Humanity, he has been working with Professor Wendy Rogers and Professor Charlie Kemp, an engineering professor at Georgia Tech and CTO of a company called Hello Robot, on the topic for more than a decade.

It has been a great relationship, and it got even closer last year when the group began collaborating on a Small Business Innovation Research grant from the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health. The grant is what brought Stretch, which is built by Hello Robot, into Evans’ home. With an assist from a doctoral student in occupational therapy from Pacific University, Vy Nguyen, Evans learned to control Stretch using a web app and a device that translates the small movements of his head into cursor movements on a standard laptop.

By the end of its stay, Evans was using Stretch to scratch his own head and feed himself. Stretch delivered poems, fresh off the printer, that Henry composed for his wife, Jane. Jane also received recipes that Henry had picked via Stretch, as well as delivery of a rose when she entered the room.

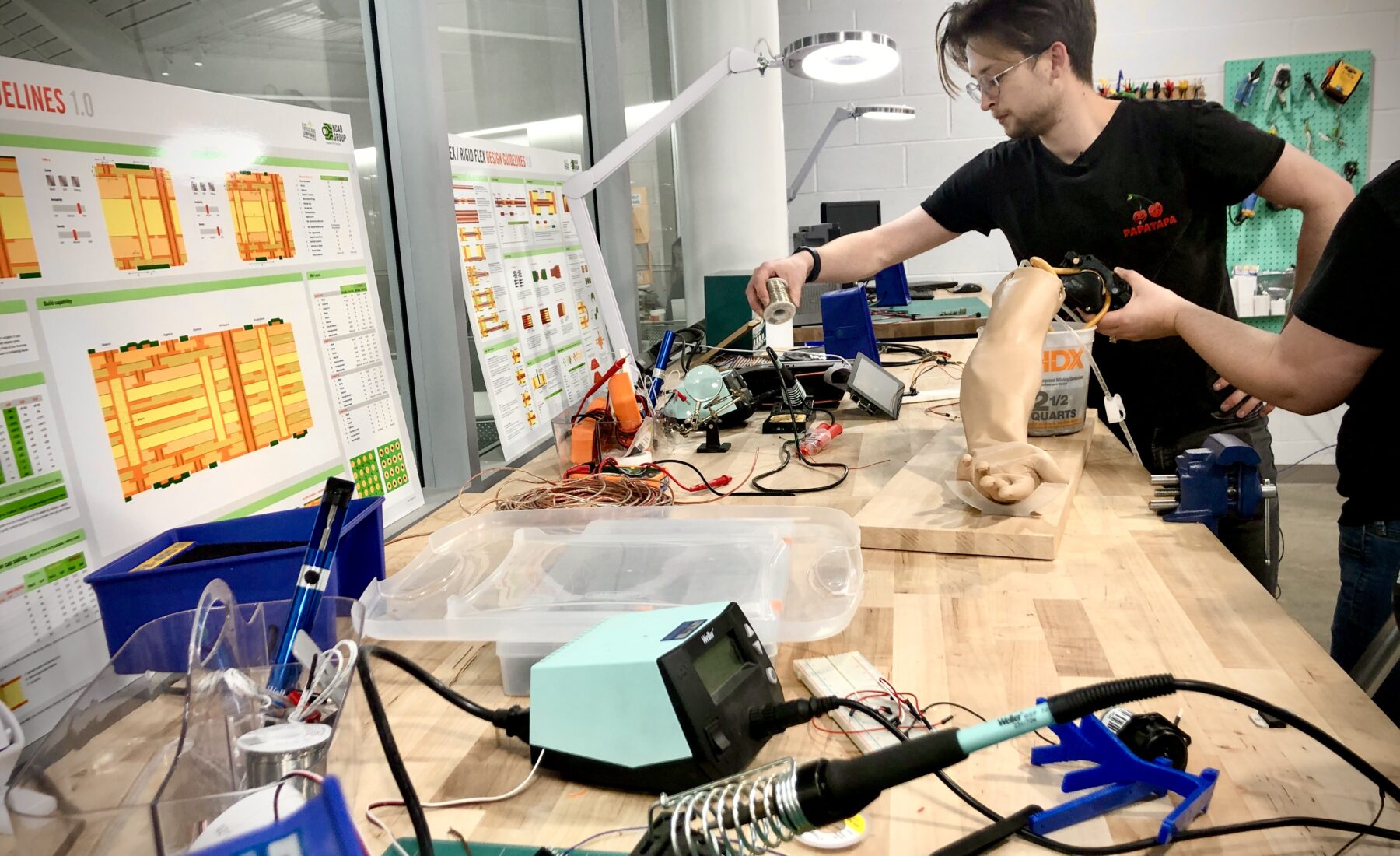

While the Evanses, Kemp, and Nguyen were at work in California, Rogers and her team were at work in Champaign-

Urbana. They interviewed older adults about their reactions to the Stretch robot, tinkered with 3D-printed attachments that might improve Stretch’s performance, and kept a close eye on the user experience that the Evans family was having.

The Evanses found Stretch wasn’t indispensable—a nurse or aide could have done what it did. But Stretch was invaluable.

“We have to ask ourselves over and over, why robots, when a caregiver can do it ten times faster? I see what it does to my husband mentally when he can do things by himself and not depend on anyone,” Jane Evans told the researchers. “This is huge, because it translates to one’s mental state. [Over the years, robots] gave him a reason to live.”

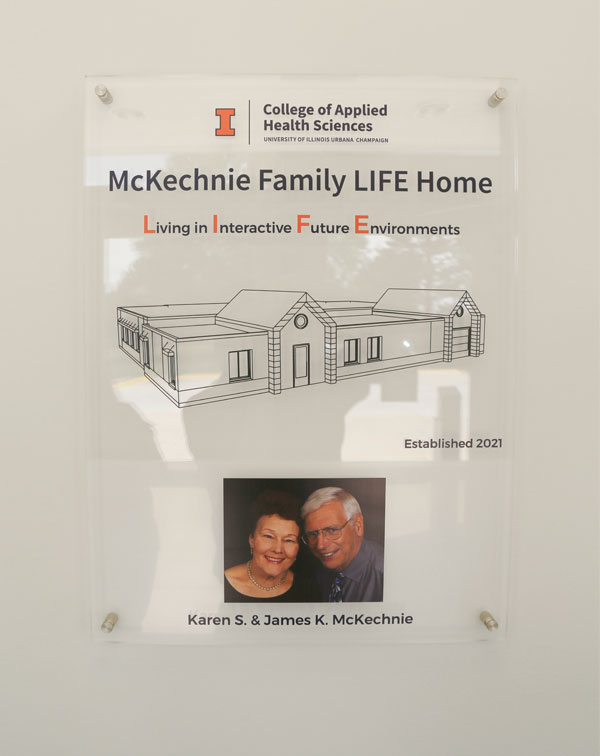

Living In Interactive Future Environments

On campus, both Rogers and the Stretch robot use the McKechnie Family LIFE Home as their base of operations. The LIFE (Living in Interactive Future Environments) Home opened in the fall of 2021, and students and faculty from across campus use it to develop and test technologies that may someday help people live more independent and more satisfying lives, regardless of age or ability.

Unlike most buildings on campus, the LIFE Home looks like what many of us would call home. A gabled roof. An attached garage. A modern kitchen with stainless-steel appliances and the requisite island. An open-concept dining area leads directly into a living room complete with orange and blue couches and a flat-screen TV.

Local photographer Larry Kanfer’s photographs of prairie scenes hang on the walls. It’s a two-bedroom, but—in a move familiar to empty nesters everywhere—one of the bedrooms has been converted to a study and comes complete with a fireplace.

It’s homey, mimicking research participants’ actual living spaces. But it is also standardized—every person being studied is working in the same space, reducing the variations and challenges that come with conducting research in peoples’ homes. Audiovisual equipment, cameras, computer equipment, and other technology are in place for the researchers as well. It’s a plug-and-play world, where they can develop ideas in their labs, bring them to the LIFE Home, set them up, and efficiently get going on their work.

“It’s a really clever design, meant to foster collaborative research. We’re coming from different buildings and perspectives. The LIFE Home creates a space where people can land and work together,” said Professor Shannon Mejia, who uses the LIFE Home to study health, aging, and technology in the College of Applied Health Sciences.

What You Want, Where You Want, When You Want

For years, researchers have defined “successful” aging as the ability to perform essential activities of daily living, things like brushing your teeth or eating. Researchers also consider instrumental activities of daily living, like paying your bills, cooking, and tidying the house.

However, Rogers and some of her colleagues include a third concept that they call enhanced activities of daily living. These are the things that make life more than just getting by, like talking to friends, hobbies, and volunteering, or maybe hand-delivering your wife a poem by robot.

To put it more simply, Rogers describes successful aging as being able to do what you want, when you want, where you want, and with whom you want.

These activities, especially when done independently, improve a person’s health and well-being. Technologies that help people with these activities should do the same, according to Rogers.

“There are many clichés about home. Home is where the heart is. Your home is your castle. I think about home as where you want to be. It provides a sense of comfort and support. And as we introduce technology into the home, we should be enhancing those feelings,” she said.

Some technologies more readily make a person feel supported than others, and much of the research conducted by Rogers and other faculty in the LIFE Home focuses on that. They interview older adults on how robots make them feel and how the robots could help them; they conduct usability experiments to improve the usefulness of devices like Amazon Alexa and develop instructional support tools; they design support systems to help people with hypertension remember to take their meds; they build new software and hardware to improve the performance of technology that is already on the market; and they develop emerging technologies of the future.

By rigorously and quantitatively assessing people’s responses to future technology and understanding their needs, they can make it more accessible and improve lives.

“I was working with Stretch the other day, and it brought me a water bottle,” Rogers said to a group touring the LIFE Home recently. “I told Stretch, ‘Thank you.’ Thank you? I don’t tell my car, ‘Thank you, Car, for getting me to the grocery store’ when I get out. What is that? It’s all technology, but what are these differences in how we understand and react to and use these technologies?”

Stretching the Limits of What a Robot Can Do

Professor Katie Driggs-Campbell, a roboticist in the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, uses Stretch in the LIFE Home, too. Her team is designing a wayfinding robot for people with visual disabilities, starting with a needs assessment in collaboration with the Rogers team.

Think of a service dog. Only rather than holding a German shepherd’s harness, a person would hold Stretch’s “hand.”

Driggs-Campbell studies what she calls “human-centered autonomy.” She develops algorithms that model human behavior so that computers can better predict how people are going to behave. Autonomous technologies, more and more, are functioning alongside people—whether they are in a healthcare facility, a factory, a farm field, or a car. So, they need to operate safely, and people need to be able to interact with them fluidly.

“You can’t design these robots in isolation,” she said. “How a person moves and how they are going to respond to the robot is coupled to how the robot moves. And the robot has to communicate what it intends to do.” In the case of a wayfinding robot, that might someday include a tug, vibration, or sound.

The robots also have to be able to navigate a space they’ve never been in before, with or without a human at hand. That means understanding the “semantics of the room,” such as where the obstacles and doors are and clues that might let a robot figure out that it is in a kitchen or a bedroom. By collecting data from sensors like cameras or LIDAR (which is like radar, using laser light instead of sound), the team’s algorithms will be able to determine the layout of a house, position the robot in that landscape, determine where its human user is, and guide the user.

“The LIFE Home is a perfect playground for us,” Driggs-Campbell said. “In robotics, there’s almost always a lab bias. You can get about anything to work in your perfect, controlled lab. The LIFE Home gives us the chance to translate [our experiments and testing] to something that is much more realistic.”

“And with the LIFE Home we also get Wendy. She has just a ton of experience working with people on usability issues.”

Hello Robot’s Kemp recognized Rogers’ skill in that area, as well. “She is a grounded visionary. Our shared goal is for people to benefit from robots on a daily basis. If people don’t find a robot useful and easy to use, they’re unlikely to use it. So, Wendy’s focus on people is essential.”

That’s Who We’re Designing For

When a new student or collaborator joins Rogers’ research team, they add their photos to the team’s roster of “Elders in our Lab.” It’s a collection of pictures of family members and friends who are older, kept up to date in a PowerPoint slide. It’s filled with pictures of grandparents, parents, and other family members.

“Every presentation we give, there they are. That’s who we’re designing for. It reminds us of who we want to think about,” Rogers said.

It’s easy for a 25-year-old grad student to forget, and it’s something the rest of us often try to put out of our mind, but we all get older.

Whether suddenly or gradually over time, we all face changes in our physical and cognitive circumstances. We’re all left to navigate those changes—to figure out how our worlds will expand or contract and to explore what tools we’ll use to manage and, hopefully, thrive.

In January 2022, about twenty years into using assistive health technologies, Henry Evans talked to Nature magazine about his experience with the Stretch robot.

“It’s very important to me, from a sense of self-worth, to do things for myself independently whenever I want, even if it is slower,” he said.

His goal sounds a lot like Wendy Rogers’ goal of helping people do what you want, when you want, where you want, and with whom you want as they age. And, together, they’re making it happen. To support the McKechnie LIFE Home, visit: lifehome.ahs.illinois.edu/donors

This story was published .