There was a time when the coastline of Peru was dotted with hundreds of thousands of Humboldt penguins. They thrived on the South American shores, had plenty of fish to eat in the waters right off the beach, and built nests in the large guano deposits in nearby caves and cliffs.

But today just over ten thousand penguins remain in Peru, with a global population of approximately forty-five thousand. They, along with other seabirds and mammals that call the coast home, have seen dramatic population declines—especially during El Niño years when the Pacific waters warm to above-average temperatures. Those warm waters are less nutrient-dense, causing massive amounts of fish to either die-off or swim deeper in search of colder waters, leaving penguins without their food source. The changes in ocean temperature combined with overharvesting of both fish and guano (used in the fertilizer industry) and other human influences have caused the penguin population to drop to a fraction of what it was just one hundred years ago. The loss of just one species can have devastating cascading effects on many others.

By combining fieldwork in Peru with their expertise caring for Humboldt penguins at the Brookfield Zoo, located just outside Chicago, two Illinois grads are among the many hoping to turn the tide for these endangered animals.

✦ ✦ ✦

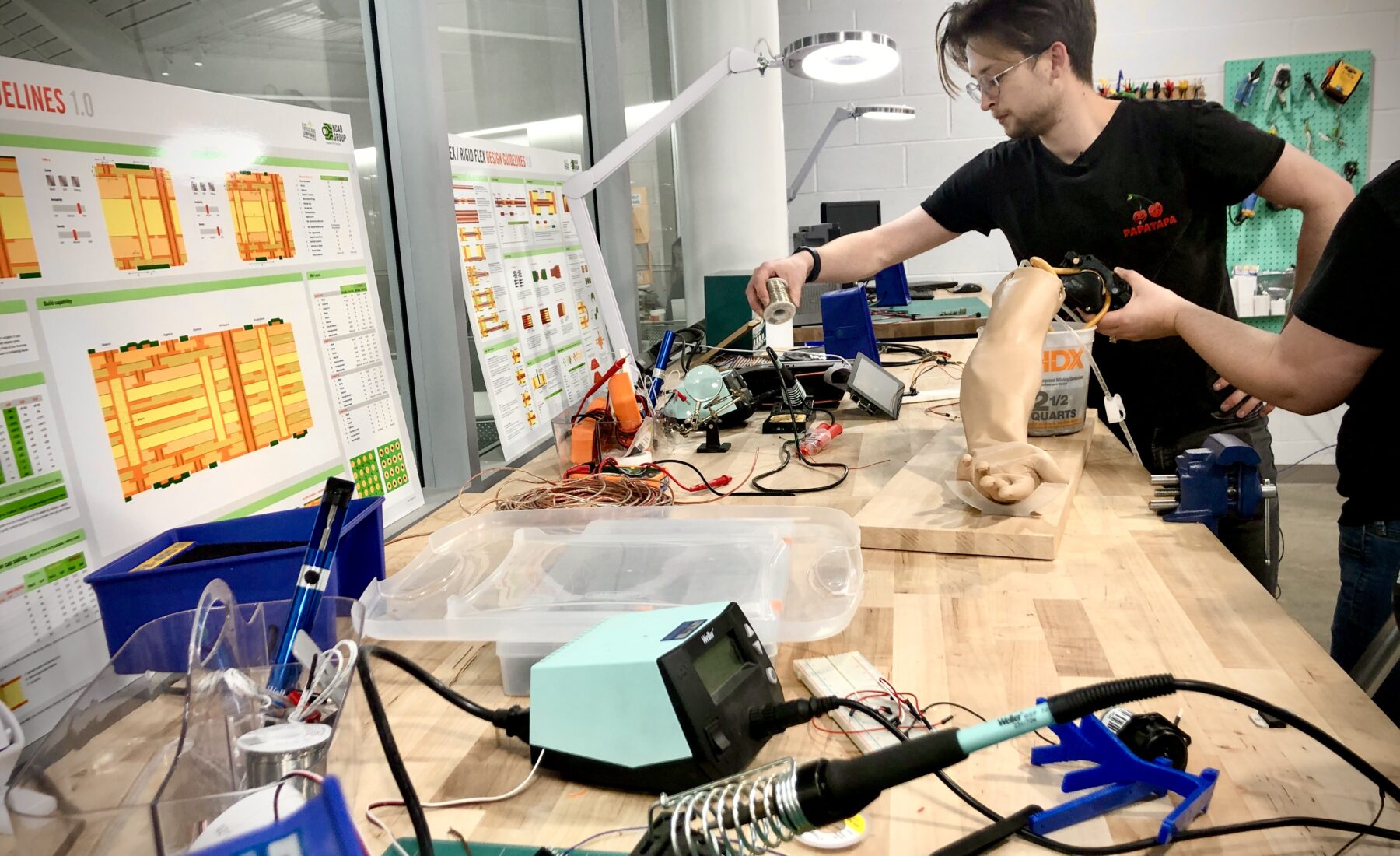

Dr. Jen Langan (VETMED ’94, ’96) holds a weeks-old Humboldt penguin chick, the blue of her latex gloves bright against the penguin’s downy black feathers. The chick has splayed legs, making it very hard for him to walk. His caregivers noticed it early and brought him to Dr. Langan, who applied bandages to hold his legs in position. Today, Dr. Langan is checking on his progress.

She handles him gently, listening to his heart, feeling his hips; the chick’s chirps echo off the sterile surfaces of the examination room. He is progressing just as Dr. Langan had hoped. Done with his exam, his caregiver takes him home to The Living Coast exhibit, where he joins the twenty-nine other Humboldt penguins that live at the zoo.

Although penguin chicks can grow to be up to thirteen pounds, they are among Dr. Langan’s smaller patients. This examination room is wide and the tables are large to accommodate just about all of the over three thousand animals at the zoo—from the tiny turquoise dwarf gecko to some of the zoo’s biggest residents, such as the polar bears or big cats.

Dr. Langan is a senior staff veterinarian at the zoo as well as a clinical professor with Illinois’ College of Veterinary Medicine. In fact, she was the first zoological faculty specialist to be hired at Illinois, and she has helped expand the zoological offerings in the college over the last fifteen years.

There was never any question she would make a career of caring for animals. “One of my first memories is watching wildlife programs with my dad,” Dr. Langan says. “My parents appreciate wild places and wild things. They taught my sister and me to respect those special places, keeping them protected for all things on earth.”

Her work at the zoo has allowed her to push into those wild spaces. Over her career, she’s been involved in a number of animal conservation projects, including work with Goeldi’s marmosets, dolphins—and the Humboldt penguins of Peru.

JOINING THE EFFORT

Behind his measured and professional voice, one can also hear the ebullient passion and intense focus of the once eight-year-old Mike Adkesson, who as a boy launched his zoological career as a youth volunteer at Decatur’s Scovill Zoo. Now Dr. Mike Adkesson (VETMED ’02, ’04) is vice president of clinical medicine for the Chicago Zoological Society, which runs Brookfield Zoo. Like Dr. Langan, his passion for animals is a lifetime in the making.

“My connection to zoos has always been an incredibly strong part of my life,” Dr. Adkesson says. “I’m so thrilled to be able to do what I do today—not only working with animals in a zoo setting, but to be able to expand that and work with these animals in the wild.”

Dr. Adkesson is one of the original veterinarians to become involved in this conservation project with Humboldt penguins, an undertaking he began during his veterinary residency at the Saint Louis Zoo, when he was still a graduate student at Illinois. Veterinarians there asked if he would be interested in doing fieldwork in Punta San Juan, Peru.

Originally, the plan was to capture a one-time snapshot of the Humboldt penguins’ health. Having been a student of Dr. Langan’s, he asked if she would be interested in collaborating. Both Brookfield and the St. Louis zoos had been doing general conservation work in Punta San Juan for several years by the time Dr. Adkesson and Dr. Langan took their first trip.

“It was a site and a project that I fell in love with,” says Dr. Adkesson. “I became really passionate about it and have been able to add to the project year after year.”

That was 2007, and since that time, Dr. Adkesson, Dr. Langan, and the other veterinarians and biologists that have worked onsite have expanded their work to include annual census counts and health assessments, as well as research into disease markers and exposure to envi- ronmental toxins. Their ability to collect long-term data in the wild as well as at the zoo has given them a greater understanding of the challenges the Peruvian penguins face and more information with which to save them.

EVOLVING CHALLENGES

Located on the Pacific coastline of Peru, the Punta San Juan Marine Reserve is a critical breeding ground for Humboldt penguins. Upwards of fifty percent of the total breeding population resides in that 150-acre site.

The area was designated a marine reserve in 2009, two years after Dr. Adkesson and Dr. Langan’s first trip. This allowed for further government-supported protections to be put in place, including stronger enforcement of regulations on guano harvesting, access to the reserve, and fishing operations in the coastal waters.

The reserve is adjacent to the town of San Juan de Marcona, a town that has grown up around the Marcona iron mine. Chinese steelmaker Shougang Group owns the mine and is in the middle of a $1.3 billion expansion. While the marine reserve is currently a monitored, safe place for wildlife, both the mine and the local increase in human population pose risks to the animals.

“One big concern is what is coming out in the effluent [or liquid waste] that is dumped into the ocean off of that mine,” says Dr. Adkesson. “Also, because the community has continued to grow over the past couple of decades, there is an increasing amount of garbage and waste that is all being dumped into the ocean in this area. We are trying to characterize and get a better handle on what impact that may be having on the wildlife and their reproduction.”

Another threat to stabilizing the penguin population is the expanding poultry farming that is taking place on the beaches along the coastline. While the penguins and the chickens are physically separated, the nearly five hundred thousand sea birds that share the coastline travel freely between the two groups. This increases the possibility that a virulent virus will be introduced to the penguins, further weakening the population and possibly causing an increase in deaths. These human factors compounded with El Niño events contribute to the penguins’ unstable environment.

“This wildlife has adapted to having their population crash and rebuild, especially after El Niño events. That has been going on for hundreds of thousands of years,” says Dr. Adkesson. “What they are not accustomed to are all the additional pressures that humans are putting on to that system. If you have a weakened population because of disease, toxins, loss of nesting habitat, or encroachment by people and now you start having these crashes from El Niño—that can be devastating on the wildlife and their recovery can take even longer.”

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS

In order to manage the populations of animals that are threatened with extinction, the Association of Zoos & Aquariums created the Species Survival Plan (SSP) Program. Each survival plan brings together scientists and veterinarians in an effort to research, track, manage, and care for a specific animal. Nearly five hundred species currently have an SSP, including Humboldt penguins. These partnerships between zoo veterinarians and scientists provide benefits to animals in the wild as well as in the zoos.

“There are things we learn from the free-ranging animals that help us provide better care for the animals in a zoo or aquarium, and there are things we learn in a zoo or aquarium that we could never learn in the wild because we don’t have that contact or length of time with the free-ranging animals,” Dr. Langan says. “It is the combination of the two that really provides us with the greatest understanding of those species and how they best thrive.”

Brookfield Zoo is only one of the partners overseeing the penguins’ survival plan. They work closely with the St. Louis Zoo, Kansas City Zoo, and Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo, as well as with scientists, veterinarians, volunteers, and NGOs in Peru.

The team developed a post-mortem exam guide, so should the Peruvian scientists find die-offs of water fowl or penguins, they know how to collect samples in order to begin a forensic investigation. This will help them learn what may have contributed to the deaths so they can try to mitigate the problem.

Being able to share expertise in other countries builds local capacity while simultaneously advancing the science. “It is an opportunity for us to do scientific work safely, but it is also a chance for us to teach local veterinarians and scientists to be an asset to other conservation projects,” says Dr. Adkesson.

✦ ✦ ✦

There are no quick and easy answers to protect a species that faces multiple threats, both natural and human-made. But these efforts on behalf of the Humboldt penguin and their sea mammal neighbors have made an impact. The initial data scientists collected about population decline was influential in the government’s decision to create the marine reserve, protecting the coastal wildlife.

Dr. Adkesson notes that they are now seeing growth in the population of penguins and that it is becoming a fairly healthy and robust group. The scientific work is continuing, however, and they are exploring questions about the relationship between environmental impact and reproduction as well as whether or not Humboldt penguins in other parts of Peru are migrating to the reserve.

The relationship between zoos and conservation work around the world is strengthening. Both Dr. Langan and Dr. Adkesson hope visiting zoo animals help people better understand our world’s wild places and wildlife—and inspire them to consider how they can support conservation efforts.

“I remember during my first trip to Peru when I had the opportunity to look down from one of the cliffs and watch a group of penguins on the beach right next to the water. It is a memory that I don’t think I’ll ever lose,” says Dr. Adkesson. “You work so hard in a zoo to care for and protect these animals, and then to be there in their native habitat with them, working on a project you know can directly help in their conservation in the wild is really rewarding.”

This story appears in our latest print edition of STORIED.

This story was published .