WHEN MATHEMATICS TEACHER Maudelle Brown Bousfield told the Chicago Board of Education that she was going to sit for the principal’s exam in 1926, she recalls that they “laughed in her face.” But Maudelle came from a family that prized education as much as they did tenacity, so that didn’t deter her one bit.

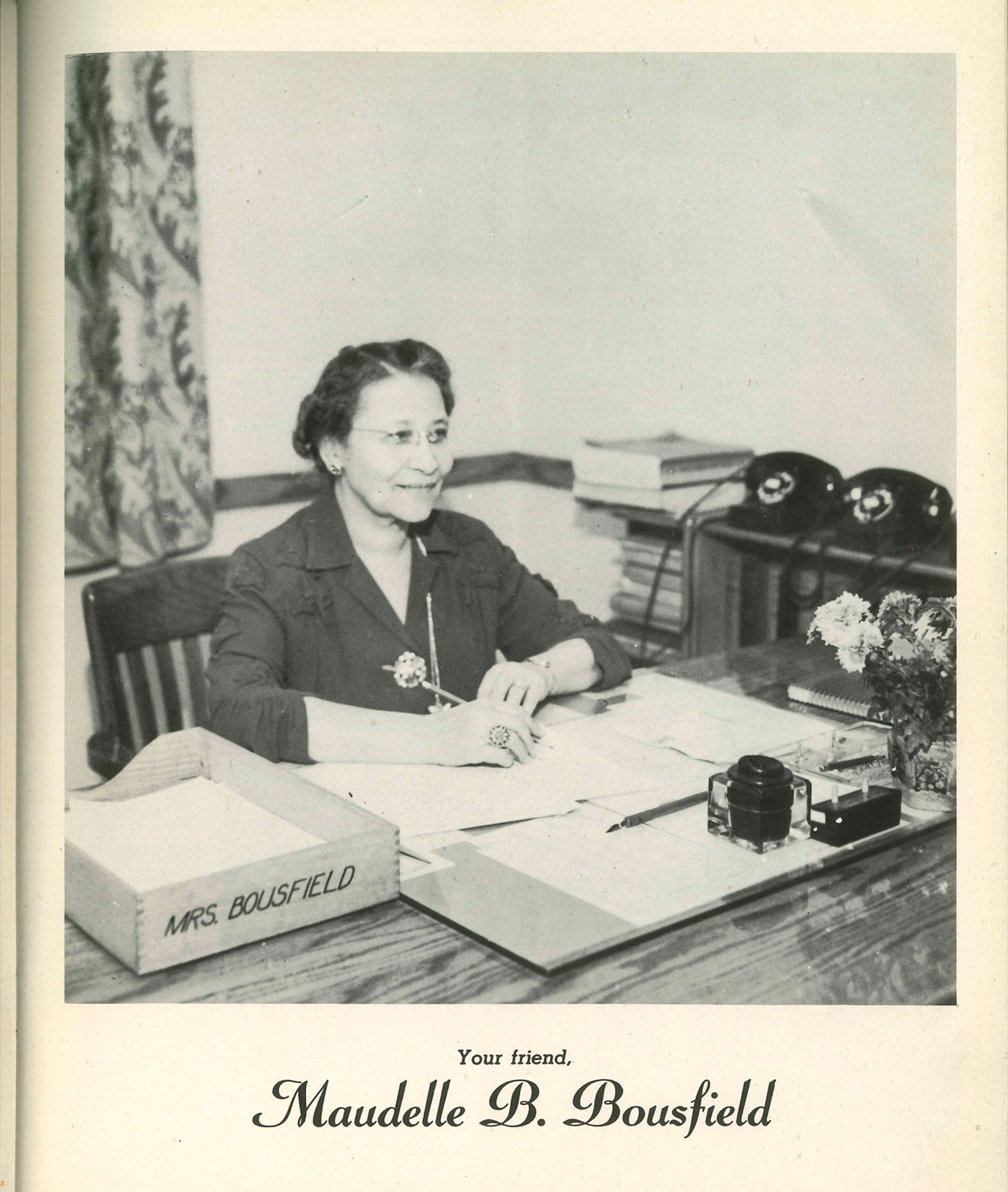

She sat for the exam and received one of the top scores, and with her appointment at Keith Elementary School in 1927, she became the first African American principal in the Chicago Public School System. She went on to become the first African American principal of a Chicago high school, Wendell Phillips in the South Side’s Bronzeville neighborhood, and served there until her retirement in 1950.

These pioneering steps were not Maudelle’s first. She was also the first African American woman to attend Illinois, arriving on campus in 1903 and graduating with honors just three years later with degrees in astronomy and mathematics. And she was the first African American Dean of Girls named in the Chicago Public School System, a position she took on in 1920, seven years before she became principal.

She felt a deep dedication to the children of Chicago, and her service to the city’s children extended beyond the classroom. She published many articles that challenged misperceptions of African American students, exposed flaws in testing, and addressed the effects of racism on the schools and the community. In a 1936 article that points out increasing racism in the North, she wrote, “The Mason and Dixon line has either vanished entirely or has moved much nearer [to] Canada.”

As an active and prominent Chicagoan, she served on many boards and committees. In fact, from 1946 to 1950, she served as an examiner on the Chicago Board of Education—the very board that laughed at her twenty years earlier.

In 2013, Illinois honored Maudelle by naming its newest residence hall after her. Speaking to a reporter at the dedication of Bousfield Hall, one of Maudelle’s grandsons, Leonard Evans, said, “She focused on something and wouldn’t accept less than succeeding in it. She wouldn’t let you say you can’t do it. Her response would be something like, ‘Well, you’re saying you can’t do it and I’m saying you simply haven’t done it yet.’”

This story appears in our latest print edition of STORIED.

This story was published .