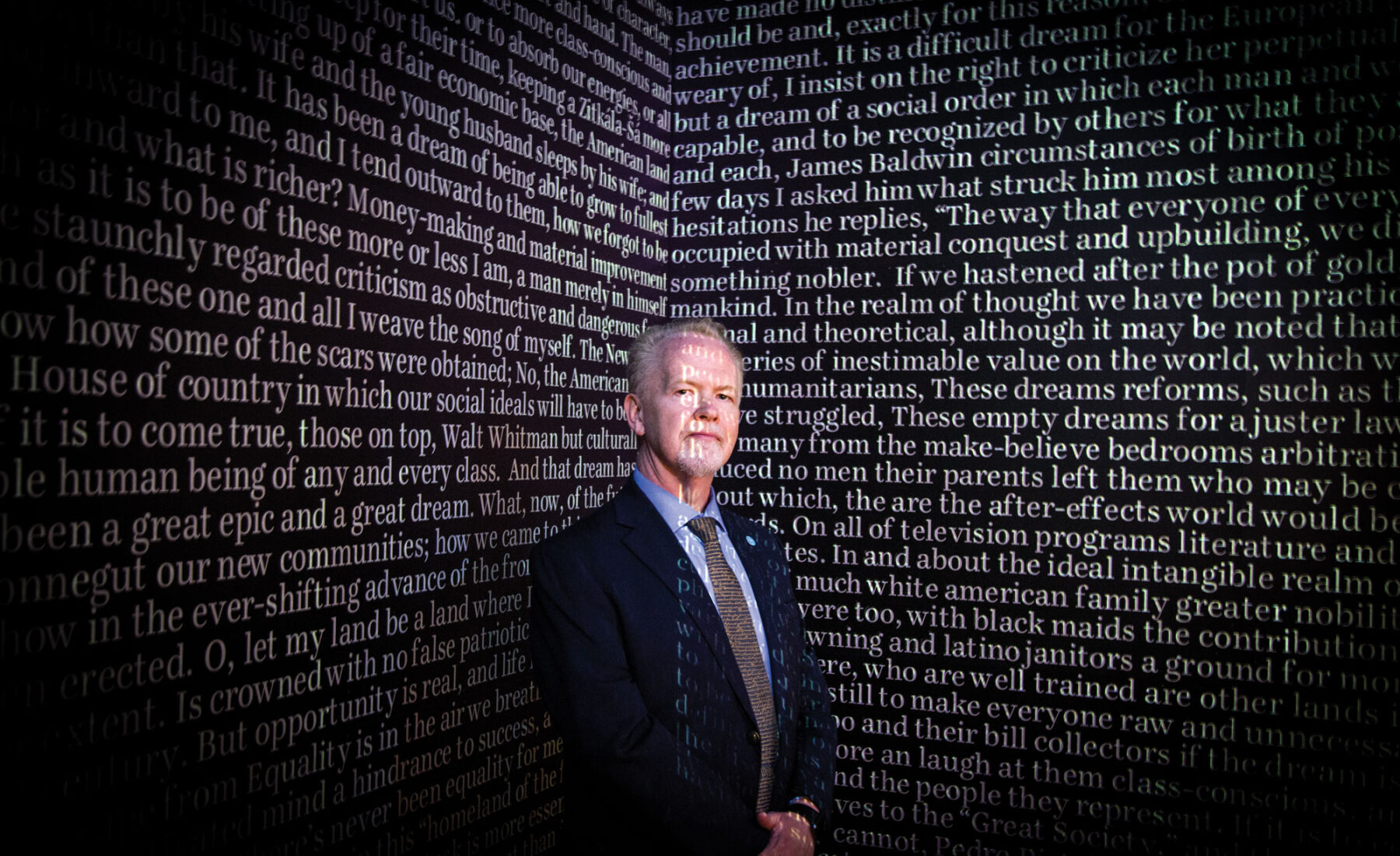

In the very back of the American Writers Museum there is a corner where two walls meet, each filled from top to bottom with words, seemingly random. The light is low, and people gather as a projector illuminates these words to highlight quotes from famous authors and create shapes such as rolling waves and the distinct torch of the Statue of Liberty. Every eight minutes it refreshes itself and is mesmerizing to watch. It creates meaning out of disorder, ever-changing both in perspective and content.

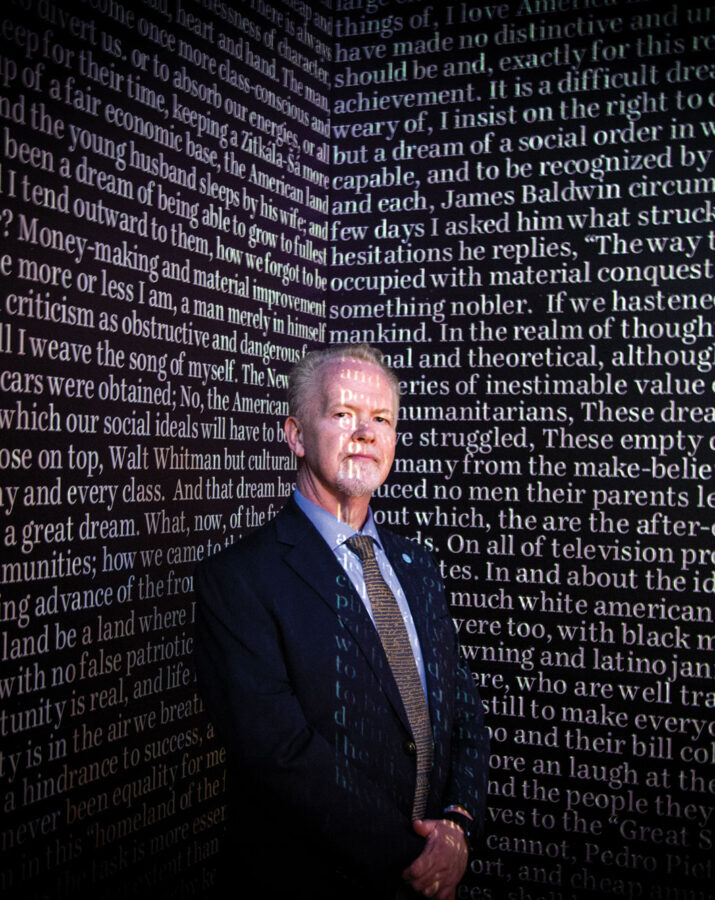

It is often said that as we further advance our culture we stand on the shoulders of giants. Carey Cranston (iSCHOOL ’05), president of the museum, might argue that it is not their shoulders we stand on, but their words.

“The written word is what this country was founded on,” said Cranston. “It is a unique part of our culture and our history. From the Declaration of Independence on, the written word has moved this country.”

It seems only fitting that writing, then, so powerful a force in our culture, has a museum dedicated to celebrating it. After nearly a decade of planning, the American Writers Museum opened on Michigan Avenue in 2017.

The museum includes permanent exhibits that trace how, over time, an American voice has developed. All types of writing are represented — from novels to sportswriting, comedy to poetry. Interactive exhibits feature video from experts discussing common threads that tie this multitude of voices together, such as the exploration of identity, the notion of independence, and the promise of being American.

There are also two temporary exhibit spaces where visitors can dive more deeply into an artist or genre. The curators have created immersive exhibits such as the one dedicated to the words of W.S. Merwin, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who also cultivated one of the world’s largest and most diverse collections of palm trees on his land in Hawaii. The museum filled the space with palm trees and the ambient sound of rainfall, while visitors listened to Merwin’s poetry.

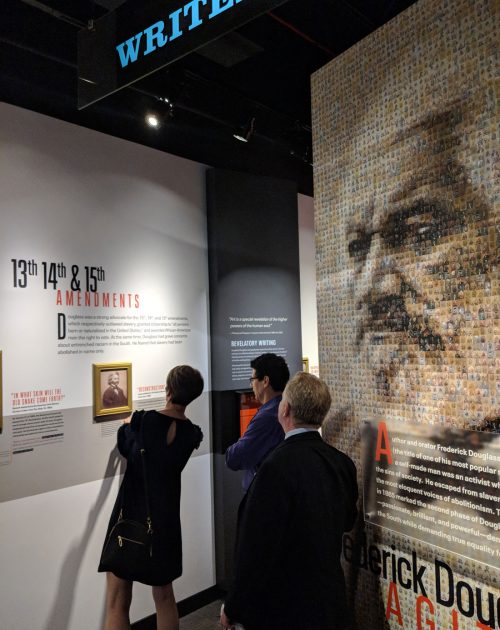

Recently the museum also featured the powerful activism of Frederick Douglass, a man who escaped slavery to become one of the abolitionist movement’s most important leaders. He is best known for his enduring autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, as well as the hundreds of speeches he wrote and delivered advocating for equality.

“One of the things [Douglass’] story tells us is that being able to read — and sometimes more importantly, being able to write — gives people power. Authorship leads to authority,” said Cranston. “If you can read, you can learn; if you can write, you can tell your story. And, if you can shape your own story, you can ultimately make decisions about who you want to be and what you want to do.”

The next exhibit being planned will feature — and is curated by — modern immigrant and refugee writers. Cranston points out that it is important to have multiple curators for an exhibit in order to avoid having a singular voice. “These authors are writing the words that shape the narrative, like Frederick Douglass did, of who we are as a nation,” said Cranston.

Cranston grew up in Homewood in a family that loved reading — dad read history, mom read mystery, and Cranston and his brother passed tattered comics back and forth between them. Cranston spent years working as a bookseller at Kroch’s and Brentano’s on Wabash before earning undergraduate and master’s degrees in literature from DePaul and the University of Illinois at Chicago and a master’s in library and information science from Illinois. He spent much of his career in higher education administration before returning to his original muse and taking the position at the museum.

“We have exhibits that celebrate the past and its influence on us,” said Cranston. “We have programs that help promote the present. Those two things are really meant to help us inspire the future. I want people to leave the museum wanting to write, wanting to read — but most of all, I want them to think about how engaging with the written word is fundamental to our collective identity.”

This story was published .