In 1946, the Nat King Cole Trio hit the Billboard charts with their song, “Get Your Kicks on Route 66.” Cole’s smooth voice transported us down the iconic road from Chicago to Los Angeles. It became the anthem of the American road trip, where vacationers sent kitschy postcards home and spent nights in roadside motels with flickering neon signs beckoning weary travelers.

But if Nat King Cole wanted to stay at one of these motels along the road for a good night’s rest, he would likely be turned away.

If he was hungry and stopped for a meal at a café, he would likely be turned away.

In mid-twentieth century America, it was one thing for white Americans to sing along when they heard Cole’s song on the radio. It was another to offer him—or any Black traveler— an available bed or a warm meal.

Black Americans had a different and often difficult relationship with Route 66. The nation’s Mother Road—so named by author John Steinbeck in his 1939 novel Grapes of Wrath—could be unwelcoming and even dangerous, mirroring the reality of travel across the country for Black Americans at the time.

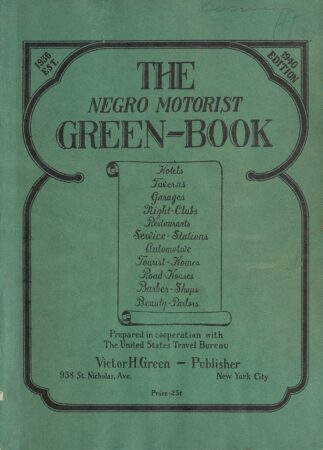

Out of this struggle, in 1936, Victor Green, a postal worker in Harlem, created the Green Book, a slim, paperback with a green-tinted cover. It listed businesses that welcomed Black patrons. By consulting the Green Book, travelers could find a safe room for the night as well as other needs—gas stations and entertainment, barber shops and beauty parlors. Along the Mother Road, the Green Book was a trusted companion for Black travelers.

Out of this struggle, in 1936, Victor Green, a postal worker in Harlem, created the Green Book, a slim, paperback with a green-tinted cover. It listed businesses that welcomed Black patrons. By consulting the Green Book, travelers could find a safe room for the night as well as other needs—gas stations and entertainment, barber shops and beauty parlors. Along the Mother Road, the Green Book was a trusted companion for Black travelers.

Route 66 cuts through downtown Springfield, Illinois on the way to St. Louis. Between 1936 and 1966, the Green Book listed twenty-two private homes, restaurants, and businesses that catered to Black travelers in this capital city—a city with a complex past.

Almost eighty years after the launch of the Green Book, Illinois alumnae Gina Lathan (AHS ’20) and Stacy Grundy (ACES ’10) opened Route History, located just one block east of Route 66. This addition to the tourist destinations in Springfield offers visitors a different perspective on the Mother Road as well as a look into the history of Black struggle—and excellence—in the state’s capital.

✦ ✦ ✦

The other side of Route 66

An unassuming brown road sign in the middle of downtown Chicago marks the start of historic Route 66. From there, the road winds through America’s heartland on its way west to California, crossing eight states over 2,400 miles. Established in 1926, Route 66 was one of the earliest public highways, unique in its east-west course that connected rural towns with big cities.

Lathan grew up in Springfield and remembers learning about Route 66, but absent from these lessons were ones about the reality of traveling during Jim Crow, the power of the Green Book, and their own city’s role in that history. Route History is their answer to amplifying those stories.

“People from all walks of life, especially our children, need to see the great contributions Black people have made to this country,” said Lathan.

After leaving Chicago, Springfield was the first stop along the route to offer services to Black travelers. With nowhere safe to stop, families had to plan ahead for those long stretches on the road by packing food and water and making sure the gas tank was full.

In the mid-twentieth century, the east side of Springfield was home to the Levee, a bustling neighborhood of Black-owned establishments. The Green Book listed a number of private homes in the city where travelers could rent a room, but the only hotel that welcomed Black patrons was the Dudley Hotel, a stately brick building on the corner of 11th and Adams. Cansler’s Lounge, which appeared in the Green Book from 1952 to 1961, was host to numerous jazz icons passing through Illinois including Ella Fitzgerald, Hank Jones, and Ray Brown.

Businesses like these provided respite for travelers but were also vital to the health of the city. “Our roads and highways played a significant part in the development of Black business and economics in Springfield. Black businesses were economic engines, but they also were a stabilizer for communities. They were a way to recycle dollars within the community and scale businesses to provide meaningful wages and opportunities for people,” said Grundy.

✦ ✦ ✦

Don’t let the sun set on you

Of course, over its history, Route 66 was much more than just a vacation route. It was critical to moving goods across the country, allowing more small towns to be linked to the distribution chain.

Like so many Black families leaving the South, Grundy’s family traveled on parts of Route 66. They journeyed from Mississippi to Chicago as part of the Great Migration, a period between 1916 to 1970, during which over six million Black American left the South in search of a better life in the North.

“Many people of color may not connect with the road because they don’t see their story in the road,” Grundy said. “But the Great Migration along Route 66 is part of my family’s story. It was a road of opportunity, but traveling that road looked very different.”

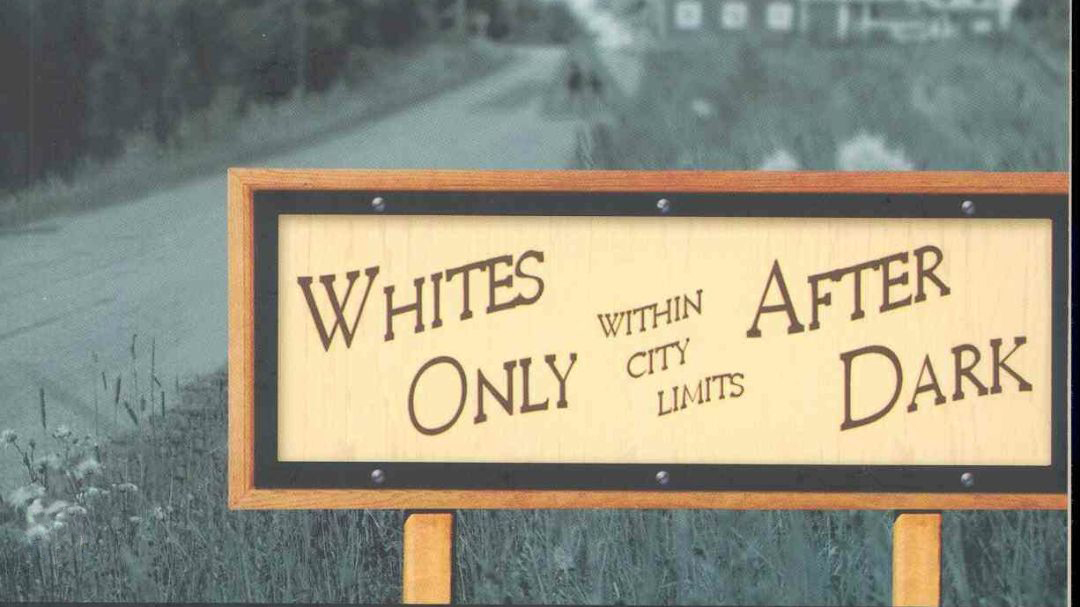

It looked different in Illinois specifically because the state was home to hundreds of sundown towns, a term used to describe communities in which Black people were explicitly not welcome after dark. It was extremely dangerous to travel through these towns.

Author James Loewen grew up in Decatur, Illinois, and went on to become a sociologist and historian focusing largely on race in America. He was best known for his book, Lies My Teacher Told Me which critiqued the omissions and revisions rife in history courses across the country. He was also the first academic to extensively research and publish about the existence of sundown towns, places the Black community had been all too aware of. His book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism sought to expose the history of these towns that he called “all-white on purpose.”

In doing his research, he expected he would find only a handful of these towns in his home state, thinking the majority of these towns would be found south of the Mason-Dixon Line. He thought he’d find maybe ten sundown towns in Illinois and perhaps fifty across the country.

What he found was that over 70 percent of towns in Illinois with a population over a thousand people—424 total—could be deemed sundown towns. He also found that the existence of sundown towns was not relegated to the distant past. Many sundown towns held on with a firm grip during the twentieth century.

One of Illinois’ most written-about sundown towns is Anna, but Loewen shares many examples in his book including Villa Grove, a town twenty miles from our campus. Shortly after the city water tower was erected in 1914, residents mounted a siren on the tower. The siren sounded at 6 p.m. to warn Black people to leave town. That sound was woven into daily life in Villa Grove for the next eight decades: the siren only went quiet in 1998.

Springfield, while not a sundown town, was surrounded by them, and so its role as a safe haven for Black travelers became an important part of its history.

✦ ✦ ✦

Rebuilding businesses, restoring a community

Route History chronicles the Black experience on the road and the Black businesses who provided respite along it. It also magnifies the stories of other historical milestones in Springfield, illustrating how the community has endured and prospered even through tragedy.

“Often we learn about Black history in terms of enslavement and that doesn’t always leave space to talk about the ways we have been able to persevere,” Lathan said. “Route History is very proud to be able to celebrate the resiliency and excellence of Black people.”

At Route History, Grundy and Lathan devote space to the 1908 Springfield race massacre, a pivotal event not only for Springfield, but ultimately for the nation.

In the middle of August 1908, the city erupted in violence after a white woman accused a black man of rape. This accusation was later proven false and withdrawn by the woman, but not before a mob of thousands of white men destroyed Black neighborhoods, setting homes alight and looting Black businesses. Members of the Illinois National Guard camped out by the state capital, and it took days to restore order in the city. By that time, sixteen people had died, thousands of Black families left Springfield altogether, and two of the city’s prominent Black residents were publicly lynched.

The nation was shocked by the violence in Springfield, and as a result, dozens of activists came together to form the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The NAACP is now the oldest civil rights organization in the country and remains a powerful voice for advocacy.

“In 1908, there were black businesses, there were black professionals, there was a thriving black community,” said Lathan. “Unfortunately, this was not a part of the history curriculum—even within the city of Springfield—until recently. That piece of history is something that needs to be shared, and it needs to be examined in such a way that we can model and replicate the greatness and move forward.”

Black businesses sustained $150,000 of damage or $4.4 million in today’s dollars. When they began to rebuild, they were compensated only a fraction of that value. With determination, Black residents rebuilt the business district in the Levee by the mid-twentieth century.

“Springfield is definitely an untapped jewel,” said Lathan. “When we stroll through history, and then reflect on what the world looks like now, we can see that Springfield’s past can teach us many lessons.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Not the end of the road

Route 66 was officially decommissioned in 1985, but its decline began years before with the expanse of interstate highways. Sections of the route were diverted, traffic flow began to favor the speed of interstate travel, and new bypasses completely sidestepped many towns that once relied on visitors for their business. Today, it is no longer possible to drive the route uninterrupted.

Black businesses suffered in Springfield, and by 1966 local government had demolished buildings along multiple blocks in the Levee, effectively erasing the neighborhood. In its place, a convention center and a large office building for the headquarters of Horace Mann, an insurance company, were built.

Grundy serves on the board of Landmarks Illinois, a non-profit organization that is dedicated to historic preservation. The two groups recently announced their partnership on a project to document every Green Book site in the state. They believe that it is essential to document and share these stories.

“As a country we have not been good at preserving cultural history, partly due to systemic racism. I think now we are realizing how much American history has been lost,” Grundy said. “This project will try to rectify that.”

Of course, many years have passed, and few Green Book sites survive. This fact doesn’t make the project less important. In fact, it makes it that much more vital.

“If we can’t preserve the buildings, we can at least preserve the stories of the people who visited them so we can have that legacy to pass down to our children,” said Grundy. “We want to make sure everyone can find their story in the road.”