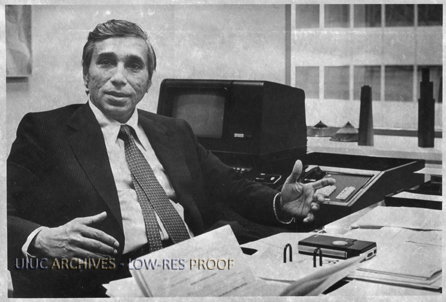

THE CHICAGO SKYLINE would hardly be recognizable without the towering contributions of Fazlur Khan (ENGINEERING ’53, ’55), the structural engineer and Illinois alumnus whose innovative engineering is behind two of the city’s most recognizable buildings.

He was born in East Bengal in British India, now Bangladesh, in 1929, to a mathematics instructor father. He came to Illinois on a Fulbright Scholarship and graduated in three years with a master’s degree in theoretical and applied mechanics, a master’s degree in structural engineering, and a Ph.D. in structural engineering.

His engineering triumph came in the form of stacked tubes that reduced the overall steel required to build his and Chicago’s two signature buildings: The Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower), built in 1973, and 875 North Michigan Avenue (formerly John Hancock Center), built in 1968. To this day, most skyscrapers built after the 1960s employ Fazlur’s structural techniques.

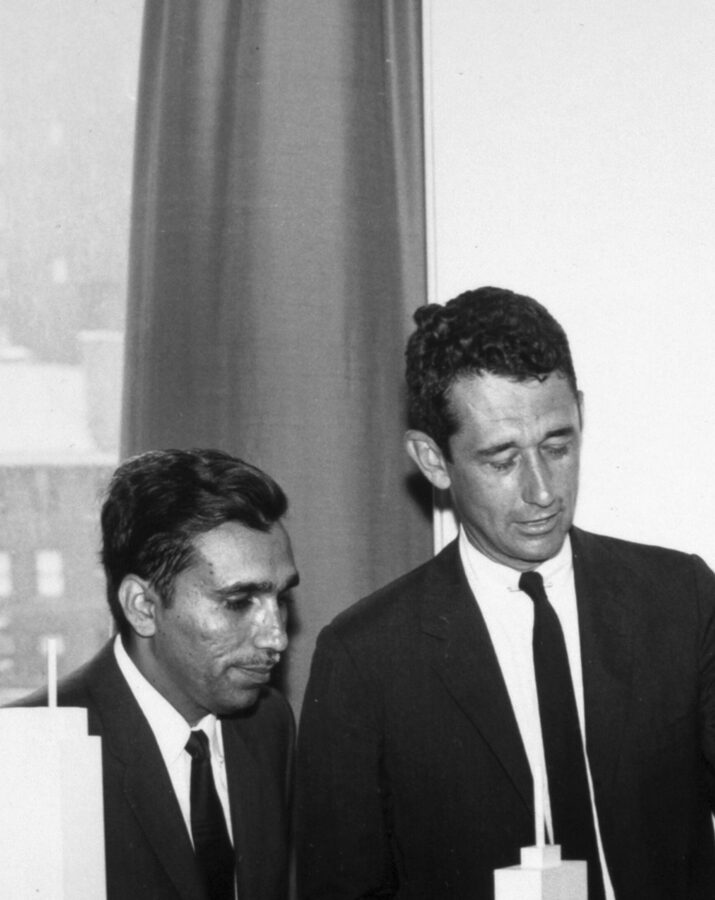

To realize his skyscrapers, he developed a close relationship with architect Bruce J. Graham, a partner at Chicago’s Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the firm at which Fazlur would spend his entire career. At the time, the reciprocal collaboration between engineer and architect was unusual, but it was very much in keeping with Fazlur’s unique philosophy.

He appreciated the intersection of aesthetics, structure, and humanity and was quoted in Structure Magazine as saying, “The technical man must not be lost in his own technology; he must be able to appreciate life, and life is art, drama, music, and most importantly, people.”

In a 2002 interview, Bruce recalled the time when “we wanted to put the columns for the Inland Steel Building on the outside in order to have a clear space inside. (Another engineer) said, ‘I can’t do it. But there’s a young engineer at the University of Illinois.’ So Faz came over, and we did it. From then on, Faz and I were buddies.”

This story appears in our latest print edition of STORIED.

This story was published .