In the early 1960s, sixteen-year-old music lover Alan Artner worked at Chicago’s legendary Orchestra Hall. His duties changed often. Sometimes he would take tickets. Other times he would wear a dark blue overcoat with mini-cape and cap and open car doors for patrons as they pulled up to the curb. By then, Chicago Tribune arts critic Claudia Cassidy (MEDIA ’21) had already earned her prickly reputation. Eventually Artner became head usher of the main floor, where he would watch Cassidy walk down the center aisle and take her usual seat on the left-hand side, just about ten rows back from the stage. There she sat in the maroon velvet seats, wearing white gloves and an elegant dress, as she waited for the orchestra to begin.

“We were all told that if critics turned up late, we should let them in,” Artner recalls. “She was never late.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Cassidy was often described as formal, sophisticated, and perfectly put together. She was raised with the Victorian sensibilities of her parents, and she carried that set of manners and that sense of decorum throughout her life. She was born in 1899 in what is now known as Old Shawneetown, Illinois, on the northwest bank of the Ohio River. Roughly 1,700 people lived in this small river town where her father was a local physician. Her first taste of the theater came on the showboats that floated down the river.

Her father’s untimely death when she was only four years old prompted the family to move to Urbana, where she eventually graduated from Illinois with a degree in journalism.

But it was in Chicago where Cassidy set down roots and where her legacy would be cemented.

✦ ✦ ✦

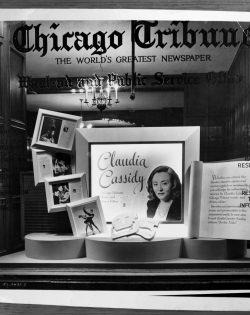

Shortly after her graduation from Illinois, Cassidy moved to the city, launching her newspaper career as the drama and music critic for The Journal of Commerce. Her break came when she filled in for the regular critic, who became ill. Sixteen years later, she was hired on by the Chicago Sun. Within a year of that move, she was hired by Tribune owner and publisher Robert “Colonel” McCormick, who greatly admired her work.

When Cassidy first came to the Chicago Tribune in the 1940s, her “On the Aisle” column quickly developed an even larger and more loyal audience. It wasn’t long before she became, arguably, the most powerful critic in the city. This was due in part to the reputation of the Tribune — it had a wide reach and was economically powerful. But Cassidy was also prolific, providing a constant flow of artfully written content that entertained her readers. People also flocked to her reviews because of her dramatic style. As Artner puts it, “They liked to read her because of her bitchiness.”

Of course, there were other papers competing with the Tribune at the time, and often Cassidy would find herself attending concerts, shows, and performances with the other critics. But, as Artner recalls, he would often come across the male critics chatting congenially in the lobby at intermission while Cassidy remained in her seat, taking notes or visiting with audience members. He observed her remaining “apart from the others. No conversation, barely a nod if she ran into them in the lobby.”

Her readership gave her a power that nobody could deny. When she published a particularly negative review, attendance could be reduced by nearly a third. This made leadership from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), Lyric Opera, and theaters across town pay attention to her. They wanted her on their side.

“If you are writing from the outside as a critic, there is a certain kind of satisfaction that comes from that. But if you are on the inside, and you are not just writing but you are getting organizations to follow your suggestions or commands, that’s another kind of power,” says Artner. “Claudia wanted that power.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Cassidy had many loyal fans among her readers, but her reputation was a little more complicated behind the scenes. She was a polarizing figure, beloved by some and villainized by others. Unafraid to speak her mind, she ran three CSO conductors out of town and scared producers away from opening shows in Chicago. Her reviews became more vicious as the years passed, with many raising the concern that she was publishing personal vendettas rather than artistic criticism.

Chris Jones is a current critic for the Chicago Tribune and the author of a book that looks back at more than one hundred years of the paper’s criticism. He notes just how hard her blows fell on the actors, directors, conductors, and others for whom she had harsh words. For example, Robert Emmett Keane, who played Captain George Brackett in a 1950 touring performance of South Pacific, fired back at Cassidy following her negative review of the show. “The reason there are so few plays running in Chicago now … is due entirely to one vitriolic woman,” he said in a speech to the Chicago Drama League. “She pours sulfuric acid over every new show which is brought to Chicago, and she scares away from the city management of every decent show which is produced in New York each season.”

For those whom she praised, Cassidy was cast as a fairy godmother, waving her pen and granting them levels of success they had always dreamed about. When Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie opened in December 1944, Jones writes that Cassidy “had to fight her way through ice and snow to get to the theater. She was surrounded by empty seats — various contemporary accounts recall a howling wind.”

Williams was lucky she made it that night. Legend holds that her glowing review changed the course of his career. Williams himself wrote: “It was an event which terminated one part of my life and began another about as different in all external circumstances as could well be imagined. I was snatched out of virtual oblivion and thrust into prominence.”

Cassidy wrote a column nearly every day — even on vacation. She carried a small portable typewriter with her on her travels and continued to file her reviews. That typewriter was sold at auction following her death in 1996, and has found its way to Alan Artner, the young usher who watched her hold court on the main floor and who went on to his own decades-long career as a critic for the Tribune.

In her later years, Cassidy retreated to her apartment in the Drake Hotel, no longer jetting off to performances in Paris or opening nights downtown. Not much is publicly known about her final years, though it is told she kept a small circle of friends close at hand.

In her later years, Cassidy retreated to her apartment in the Drake Hotel, no longer jetting off to performances in Paris or opening nights downtown. Not much is publicly known about her final years, though it is told she kept a small circle of friends close at hand.

Richard Christensen, a fellow critic and friend who ultimately wrote Cassidy’s obituary for the Tribune, recently remembered her in an interview for STORIED. “She carried herself like a queen, which she was. She knew what her standing was: she was the top-ranking theater critic of the top-rated newspaper in Chicago. And besides that, she was damn good.”

Thank you to Alan Artner, Chicago Tribune art critic and a classical music critic from 1973 to 2009 and a freelance critic from 2010 to 2018, as well as to Chuck Osgood, Chicago Tribune photographer, for assistance with this story.

This story was published .