It sounds like the familiar plotline from many a science fiction novel: intrepid explorers travel to the center of the earth and discover an entirely different ecosystem, determined to map the unknown.

It is an old story that harkens back to mythologies and folklore from around the world and made its way into scientific thought from the late seventeenth century into the mid-nineteenth century. The Hollow Earth theory, as it is known, had some recognizable and vocal proponents, including Edgar Allen Poe, who believed that one entered the interior world through access points at the extreme North and South Poles.

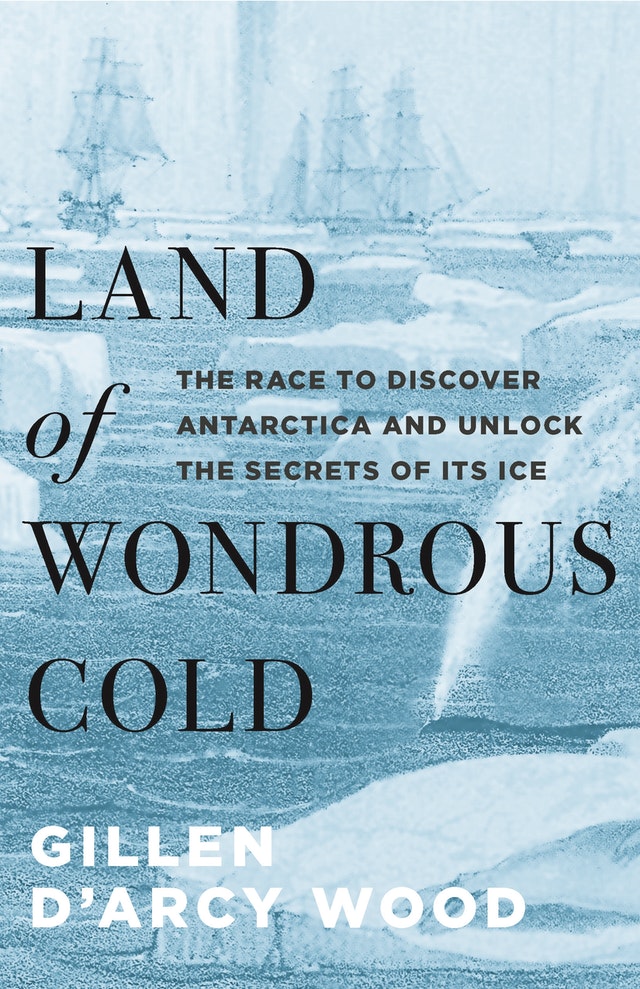

In his newest book, Land of Wondrous Cold, English Professor Gillen D’Arcy Wood brings us an environmental history of the Antarctic continent, one of the supposed entry points to the inner earth and one of the last mysteries for nineteenth-century explorers. Wood believes Antarctica is fundamental to our understanding of climate change and what threats lie ahead of us. He weaves together dramatic tales of nineteenth-century arctic exploration with modern-day efforts to understand how the destruction of the Antarctic ice cap threatens, once again, to dramatically change our planet.

In his newest book, Land of Wondrous Cold, English Professor Gillen D’Arcy Wood brings us an environmental history of the Antarctic continent, one of the supposed entry points to the inner earth and one of the last mysteries for nineteenth-century explorers. Wood believes Antarctica is fundamental to our understanding of climate change and what threats lie ahead of us. He weaves together dramatic tales of nineteenth-century arctic exploration with modern-day efforts to understand how the destruction of the Antarctic ice cap threatens, once again, to dramatically change our planet.

“The history of Antarctica, its initial glaciation thirty-four million years ago, really set the global thermostat. In a sense, it set the conditions on earth for the evolution of human beings,” Wood said. “We think of it as remote, but it is just so central to the evolution of the global climate. In a way, it is like coming full circle. Our very being was determined by Antarctic ice and so will our future, in the very near term, be determined by it.”

Wood is trained in nineteenth century historiography and literature, but his career shifted a little over a decade ago when he began looking for ways to integrate his interest in climate change into his research. “I was looking for ways to contribute to the greater cause of environmental preservation,” he said. “I thought, how can I put my training to use? For me, these books are the answer.”

The university awarded Wood a fellowship to pursue studies in a second discipline and so he took courses in atmospheric science and geology. He then published his book Tambora: The Eruption that Changed the World, which brought to life the immense cultural and physical impact the eruption of one volcano had on the planet in the early 1800s.

Wood relies on archives—both natural and historical—to create what he calls an ecological portrait of a moment in time. In Land of Wondrous Cold, he weaves together the explorers’ narratives—their diaries and their letters—with scientific data such as ocean sedimentary records and fossil records.

“This type of writing is a kind of synthesis, weaving the two languages of science and history into one story,” he said. Wood established and oversees the Certificate in Environmental Writing on campus, which attracts students from both the sciences and humanities who want to bring clear, data-rich science writing to the public.

“Our undergraduates need to be comfortable moving between the worlds of data and the worlds of narrative, the worlds of science and the worlds of culture,” he said. “In twenty years, they’ll be making large-scale life and death decisions. Our immediate situation with climate change is critical, and we need buy in from the general public. We have to push back against the credibility deficit that we’re seeing across the culture.”

“Our destiny is intimately tied to Antarctica’s destiny. There is a deep symbiosis that is reaching a critical point.”

Excerpt from Land of Wondrous Cold: The Race to Discover Antarctica and Unlock the Secrets of its Ice

by Gillen D’Arcy Wood

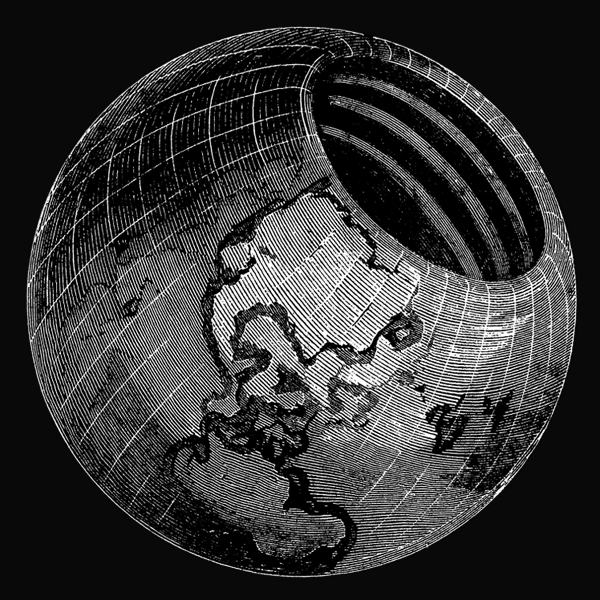

As 1838 dawned, no one knew what the three exploring expeditions would find beyond the Antarctic Circle. But one bold speculation on polar geology would prove remarkably persistent, even after their discoveries, and still may be found in rogue corners of the Internet today: the Hollow Earth theory.

Hollow Earth was a touchstone of Victorian popular imagination. In the humorous poem that opens Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll remembers taking his colleague’s daughter Alice and her two sisters out in a rowboat on a summer’s day in Oxford in 1861. As usual, the girls demanded that their father’s amusing friend tell them a story “with nonsense in it.” For Carroll (whose real name was Dodgson), satisfying the Liddell sisters’ appetite for stories was both a pleasure and a burden. In Alice in Wonderland, he imagines himself as the narcoleptic dormouse at the Mad Hatter’s tear party: he would sometimes fake sleepiness, like the dormouse, to avoid having to entertain the relentless threesome anymore.

But in the rowboat that day, there was no escape. So Carroll ransacked his memory for snatches of fun to cobble together a story. Fortunately, a lifetime’s consumption of word games, math puzzles, and pantomime shows was at his disposal. From this rich mental archive of Victorian popular culture, an oddity from childhood popped into his head: back in the 1830s, a faddish idea circulated that Earth was hollow, with openings at the North and South Poles and exotic peoples living inside. What if he shifted the northern entrance of this hollow world to a place the girls knew—say, in the nearby woods at Gosford—and told a story about Alice falling down a rabbit hole through to the center of the planet? Alice could talk to herself while she fell, and prepare to greet the strange people of the Antipodes—Alice would call it “The Antipathies”—in New Zealand, Australia, and beyond. What adventures Alice could have among the “upside down” people of an alternative southern hemisphere! From that moment’s desperation in the rowboat, the White Rabbit, Cheshire Cat, and Tweedledum and Tweedledee were born.

Lewis Carroll’s inspired notion that day was to make little Alice Liddell into a full-fledged polar explorer, and send her through a tubular Earth to a “Wonderland,” the terra incognita of the South. Alice’s first wish, as she is falling down the rabbit hole, is to become a telescope—an explorer’s signature accessory. Later, Carroll will have her neck stretch until she looks just like one. Alice’s elongated neck is the storyteller’s metaphor for time and space in Wonderland/Antarctica: a rubbery, telescopic world of perpetual mirages, where Alice is alternately miniature and giant, the White Rabbit is always running late, and the native fauna are truly “frabjous,” like cartoon relics of the Mesozoic.

Popular science fiction, like Alice in Wonderland, originates with the Hollow Earth theory, which blossomed in America with the Jackson-era mania for Antarctic exploration. A war veteran from Ohio named John Symmes launched a national campaign to explore the “holes at the poles” with a pamphlet published in Saint Louis in 1818, which he circulated to newspapers and legislators across the nation:

I declare that the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles….I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow Earth, if the world will support me and aid me in my undertaking….I engage we [will] find a warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals, if not men.

Armed with a wooden model of a hollow Earth, Symmes took to the lecture circuit where, in town after town, he earned a loyal, admiring audience, including the educated.

One convert, James McBride, took it upon himself to legitimize Symmes’s cause through publication of a serious-minded Hollow Earth manifesto. Published in 1826 in Cincinnati, McBride’s book—titled Symmes’s Theory of Concentric Spheres; Demonstrating that the Earth is Hollow, Habitable Within, and Widely Open about the Poles—is a classic of American pseudoscientific literature, bursting with data, excited syllogisms, and epigraphs from Shakespeare and Milton.

After seven chapters describing the physics and geology of the Hollow Earth, McBride makes the key connection between Symmes’s theory and the necessity for a national polar expedition to verify its truth: “for, should it hereafter be found correct,” writes McBride, “the habitable superfices of our sphere would not only be doubled; but the different spheres of which our earth is probably constituted, might increase the habitable surface ten-fold.” For a patriotic American readership, the Hollow Earth theory offered fetching visions of colonial expansion and a planet-sized virgin interior awaiting its destined embassy from the New World American metropole.

The Arctic had been crawling with British and Russian heroes of late—reducing the potential dividend of an American mission to the north—so McBride turned his attention toward the unexplored Antarctic region: “the most practicable, the most expeditious, and the best mode of exploring the interior regions would be by sea, and by way of the south polar opening, crossing the verge at the low side, in the Indian ocean, where it is presumed the sea is always open, and nearly free of ice.”

Enter Jeremiah Reynolds, a charismatic, would-be polar adventurer who provided a necessary link between the backwoods show circuit and East Coast officialdom. A gifted promoter, Reynolds first joined Symmes on his tour of the byways of Ohio and Pennsylvania, where he served as a frontman for the Hollow Earth cavalcade. To spellbound audiences, Reynolds proclaimed the Symmes gospel that Earth contained huge openings at both poles—was, in fact, a kind of cylinder—and that an American exploring fleet should be sent to claim the second New World.

When “Symmes’s Hole” became a national joke, Reynolds dropped him, but not his monomania for a South Pole expedition. He lobbied senators and Navy bureaucrats with relentless energy. In a remarkable coup, he addressed a full house of Congress with a fervent pitch for America’s destiny to rival, through oceangoing exploration, the great scientific empires of Europe. And because Reynolds’s friends in the frontier west had seen his efforts a test of their own power, they rallied the House around a bill to authorize the US Exploring Expedition, passed on May 9, 1836.

Among Reynolds’s admirers was Edgar Allen Poe, whose susceptible brain was touched with the fantastical possibilities of a vacant planetary interior. Poe, like all Hollow Earthers of his day, desperately wanted Symmes to be right. Even when Reynolds abandoned Symmes, Poe took up the polar cause of his new hero in the Baltimore newspapers. In his debut novel, published as Wilkes embarked, Poe sends his eponymous hero, Arthur Pym, on the same southward course as the American explorers. Murder, kidnap, mutiny, and shipwreck ensue—a Poe-like litany of horror on the high seas.

But the true mark of Poe’s Hollow Earthism lies in his 1838 novel’s bizarre denouement. His hero Pym’s ship sails southward beyond James Weddell’s record southing and icepack, and into an open sea. There, the accidental explorers come upon a new Earth bejeweled with tropical lands, then to the verge of the Symmesian polar opening where the concavity of the planet beckons. For Poe, geographical discovery in Antarctica was never the principal lure. Rather, the thrill of extreme polar exploration lay in the opportunity to be sucked from the surface of the ocean, via a hectic maelstrom, into the existential gloom of a tubular planet. In the last lines of the novel, Pym’s ship tumbles into a giant vortex via “a limitless cataract, rolling silently into the sea from some immense and far-distant rampart into heaven…where a chasm threw itself open to receive us.” With the hero’s ecstatic fall into a parallel inner world, science fiction, the signature popular genre of modernity, is born—via the tropic canal of Hollow Earth.

The postscript to Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym tantalizingly refers to lost chapters “relative to the Pole itself,” that “may shortly be verified or contradicted by means of the governmental expedition now preparing for the Southern Ocean.” The very month of the novel’s publication in 1838, as Wilkes’s squadron prepared to sail south, the poverty-stricken writer wrote to the secretary of the navy pleading for “the most unimportant clerkship in your gift—anything by sea or land.” Edgar Allan Poe in Antarctica? But it was not meant to be—Poe’s fantasy of cruising the hollow verge at the South Pole remained in the literary domain, in a vanguard text of the new science fiction that Jules Verne and his successors would later bring to an insatiable worldwide audience.

From Land of Wondrous Cold: The Race to Discover Antarctica and Unlock the Secrets of its Ice by Gillen D’Arcy Wood, copyright © 2020. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.