Additional reporting by Kim Schmidt

Illustrations and design by Katie Miller

In many ways, the culture of Green Street has been a reflection of the latest trends and fads, which are, by their very nature, fleeting and transient. The frequency that stores changed owners and inventory over the years, makes it difficult to truly identify a “culture of Green Street.”

Yet, what all the businesses in the photos below have in common is their intentional appeal to the students for whom they exist. When students wore tweed, they shopped at Lou Overgard; when they wanted an album, they hit up Record Service; when they wanted live music, they crammed into Mabel’s. There are a few exceptions, like Murphy’s Pub, Busey Bank, and McDonald’s, which have had a presence on Green Street for decades. But, by in large, most businesses have closed and others have replaced them with what the newest customer wants.

Green Street’s culture in Campustown will never grow old. It has been and always will be eternally youthful.

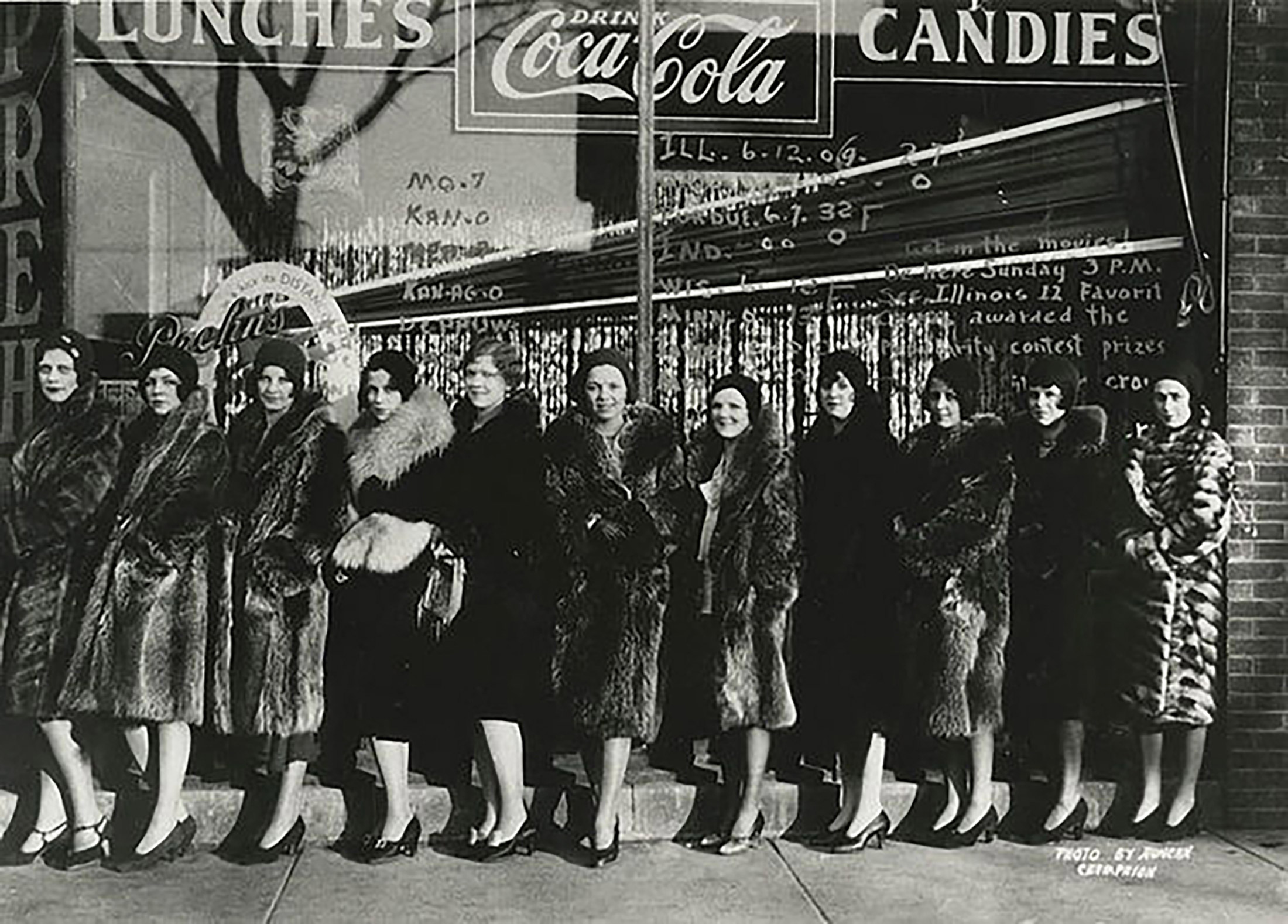

Eleven women stand outside Prehn’s Confectionary on Green Street, a popular hangout that served sodas and ice cream as well as featured a piano bar. Prehn’s also hosted dances held on the street itself, in front of the shop. Owner Paul Prehn started his career as Illinois’ wrestling coach in 1920. In his eight years in that role, Prehn won four Big Ten Team Championships. Later in his career, he became the commissioner for the Illinois State Athletic Commission. That role earned him a death threat from none other than Al Capone, who was upset at Prehn’s choice of referee for the Tunney vs. Dempsey fight held at Soldier Field in 1927.

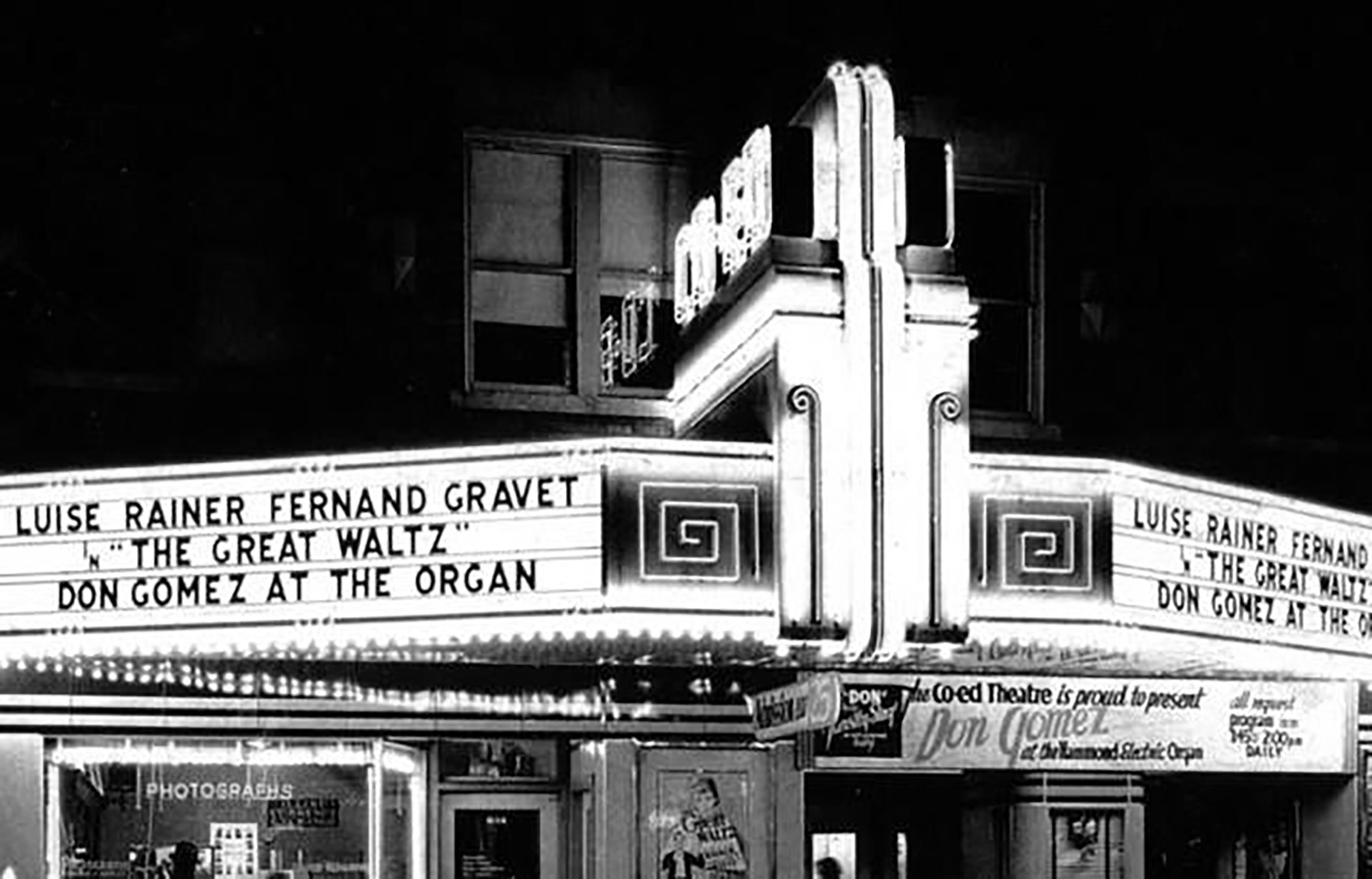

“Construction of the new Co-ed theater marks another step in the development of a campus business district that has become almost self-sufficient in 38 years of growth,” wrote the Daily Illini on September 9, 1938. Business growth on Green Street between Wright and Sixth streets grew rapidly, and the “state-of-the-art” theater fulfilled a need. Several area businesses welcomed the theater with ads in that day’s paper. Men’s clothing store, Schumacher & Kaufman, went so far as to write: “You are a welcome and needed addition to our Illinois campus. This fine, modern theater helps the rest of us is our endeavor to give the ILLINI a shopping and amusement district they can be quite proud of.”

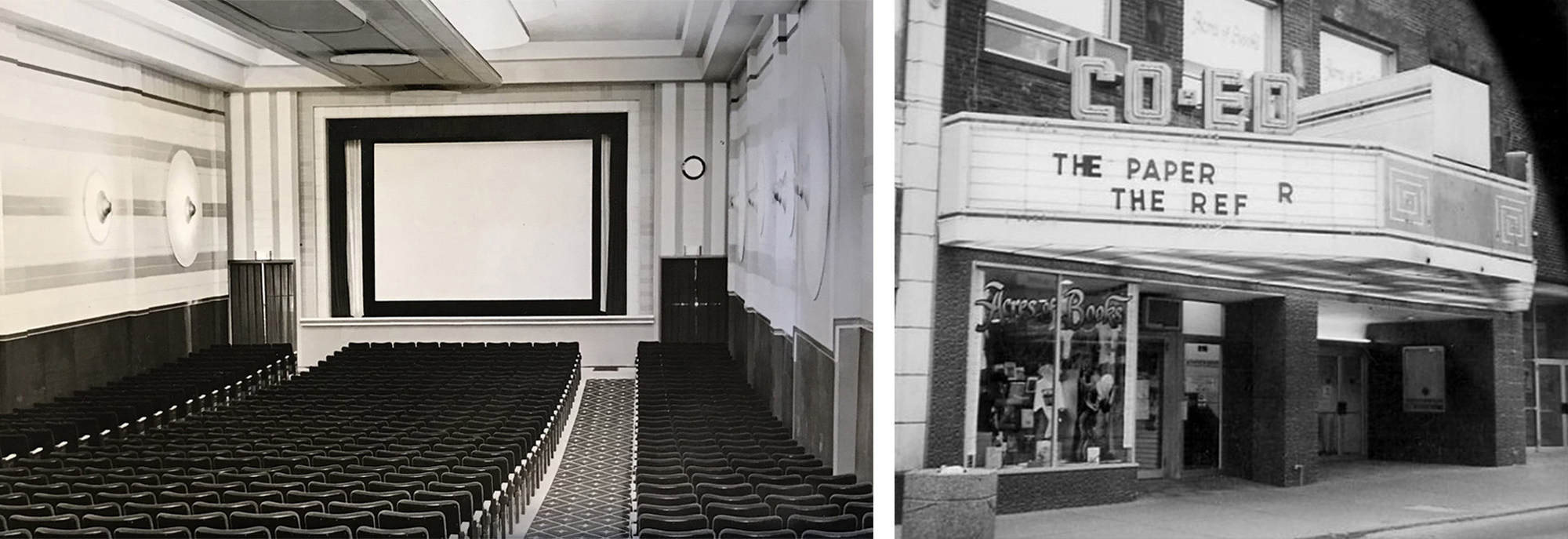

When the Co-Ed opened in 1938, the auditorium could seat 900 people and boasted modern air conditioning. The marquee was a marvel as well. “The huge marquee at the Co-ed Theater weighs more than five tons,” wrote the Daily Illini in the month it opened. “The brilliantly lighted marquee is expected to make the theater front a Twin City showplace.” The theater was a mainstay on Green Street until it was closed in the summer of 1999 and demolished in 2000. According to the Champaign County History Museum, the last movies shown were The Matrix, Notting Hill, Election, Cookie’s Fortune, and The Mummy.

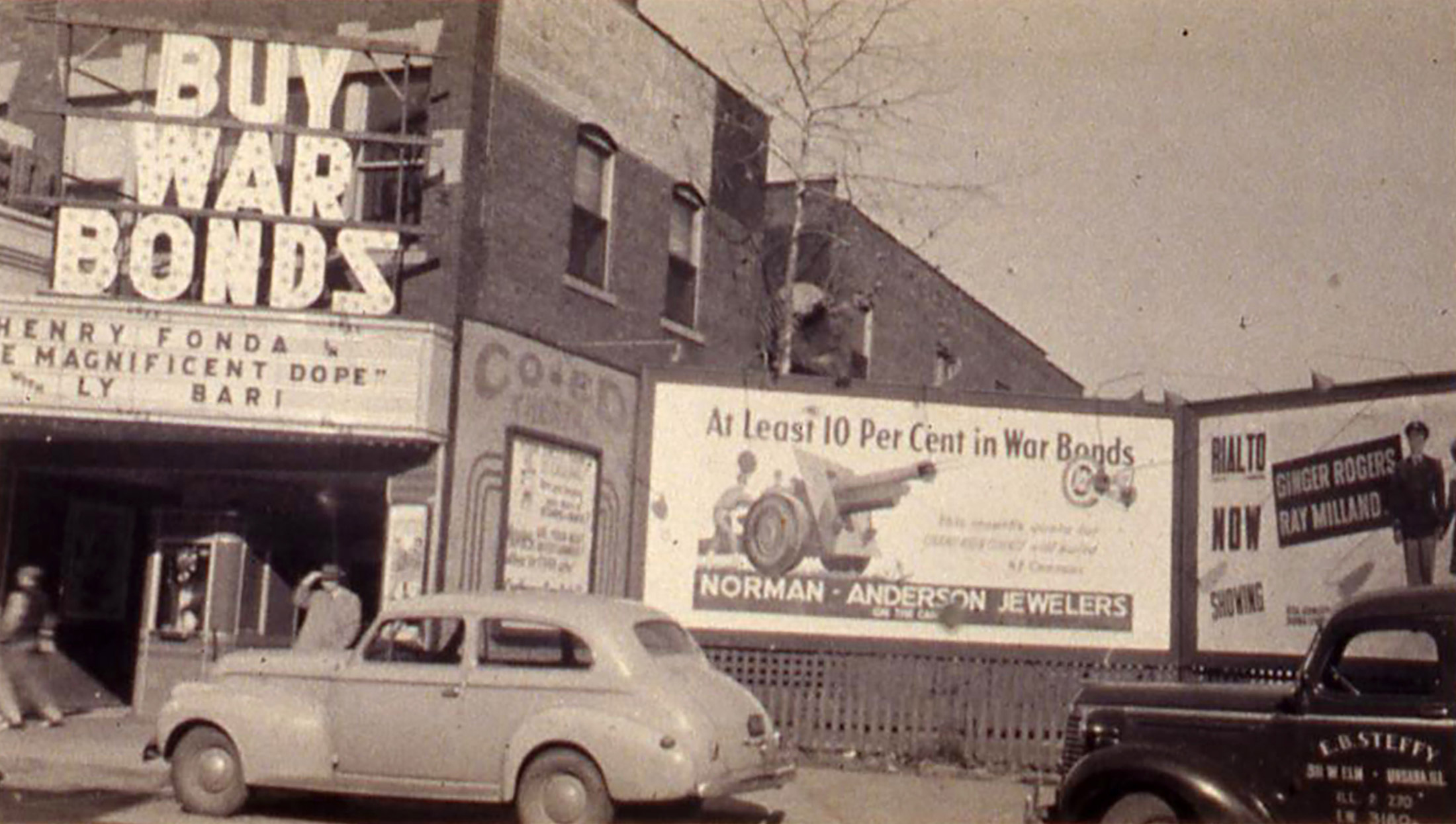

The effects of WWII were felt everywhere—including campus. The brand-new Illini Union, which was dedicated by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1942, created a Department of War Service through which students could support the war effort. A Red Cross committee prepared “kit bags” and rolled bandages, another group wrote letters to those enlisted and made sure that every Illini serving overseas received a package from home, and the local U.S.O. hosted dinners and dances for soldiers. War bonds were sold nearly everywhere, including theaters like the Co-Ed seen here.

The Marching Illini pose under the Co-Ed marquee, which displayed a mock show, “G E Smith Presents Big White Spats,” as part a photoshoot for their 1997 CD cover. “I laughed so hard because it was so creative! It was not only flattering, it was just so hilarious,” recalled Gary E. Smith, who was the band director at the time. “It was a surprise. I knew nothing about it.”

Even though Gary hasn’t led the band since 1998, he wasn’t about to divulge the significance of “Big White Spats,” the album’s title. “It’s a chant that the band does whenever we march in a parade, to one of the cadences, and it has a kind of a hidden, secret meaning. Only kids in the band know what it means. It has a story behind it that’s been handed down through the years to the new kids in the band. It’s a tradition.”

“At Overgard’s, it’s a man’s world in a man’s store,” the clothing shop boasted in a 1939 ad after it had undergone a $20,000 renovation. The owner, Lou Overgard, had just returned from a two-week trip to the East coast and was inspired to recreate a “typical Ivy League university motif,” the Daily Illini wrote in an article. Greeting customers with this “more conservative styling,” featuring bleached British oak, red furniture, and murals depicting sports. However, Overgard did include women in this redesign, with a section called the “Tweed Shop,” that carried tailored sports clothes.

A neon sign illuminates a man leaning against a column of what was once commonly referred to as the Insurance Exchange Building. Based on the locations of Follett’s Bookstore and the University of Illinois Drug store located within the building—as well as the era of the car—we think this photo was taken in the 1940s.

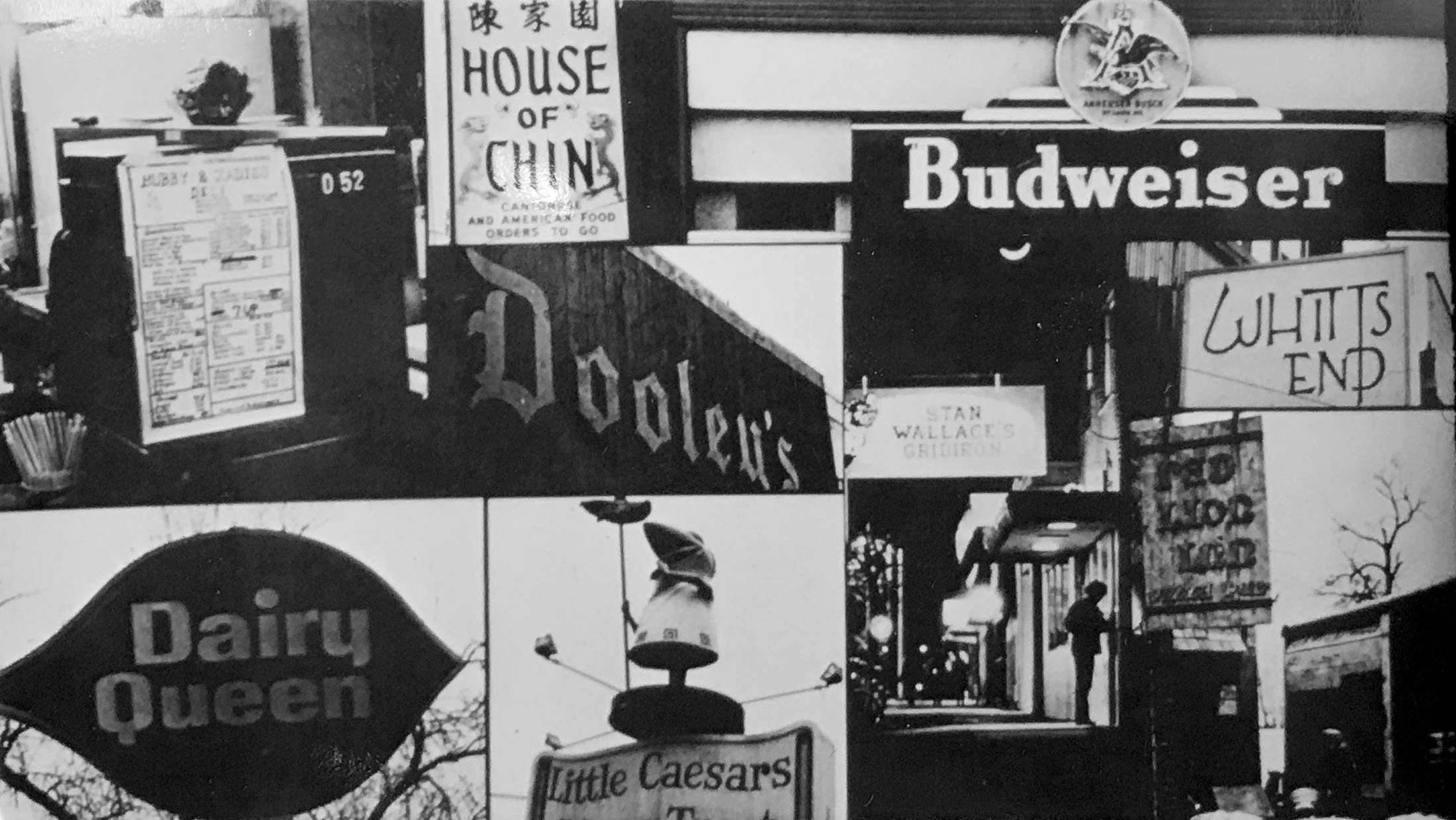

In the 1970s, Campustown was brimming with bars and restaurants—and students looking for a good time. From left, clockwise, ¬Bubby & Zaddies Deli, House of Chin, Dooley’s, Stan Wallace’s Gridiron, Whitts End, Red Lion Inn, Little Caesars, and Dairy Queen.

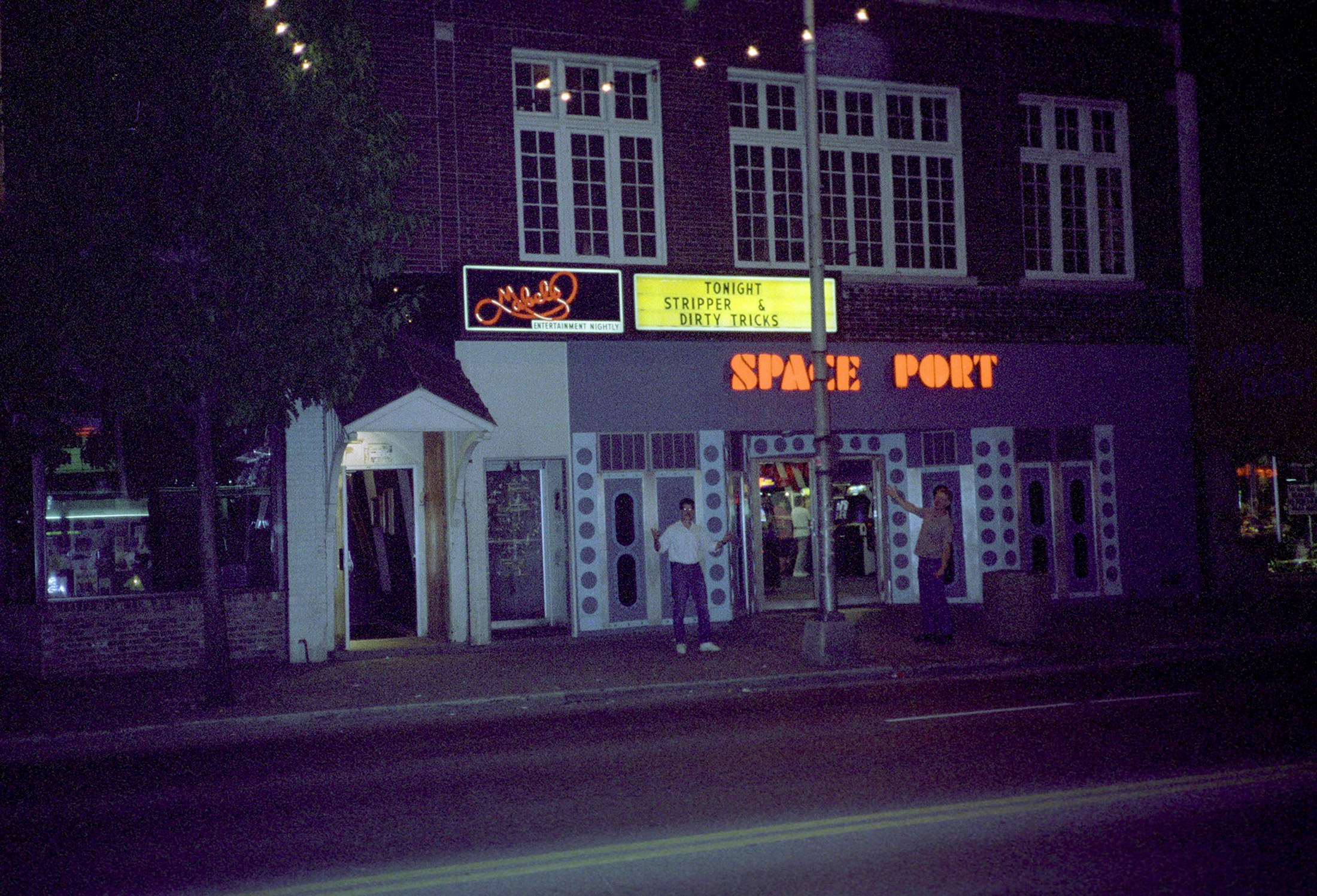

At Mabel’s peak, in the late ’70s and ’80s, hundreds of national and local bands filled the small club seven nights a week. Legally 303 people could fit in the club, although long-time owner Paul Faber admits they “surpassed that many, many times.” A full stage in the back with an oak ceiling, provided the show-stopping acoustics for acts as varied as reggae, soul, country, rock, jazz, and even comedy.“It was real happening, I mean just unbelievably happening. There were even maybe 200 local bands that could fill the place. Every night you could see a band and the place would be packed. People were really hungry for live, original music back then.” Paul recalled. “It was just amazing that we could get that quality of acts for that small of a club.”

Pioneering musician Bo Diddley, who influenced countless artists like The Beatles, Elvis Presley, and the Rolling Stones, played Mabel’s three times. Paul remembers picking Bo up at the airport, showing him around, and putting a band together for him for each visit. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon for other big-name performers like Joan Jett, Frank Zappa, Iggy Pop, Ice Cube, who had just played at Assembly Hall, to pay Mabel’s a visit.

Originally, Mabel’s, was envisioned as a wine and jazz club by first owner Eugene Pitcher (LAS ’95) in 1977. The next incarnation, cultivated by its new owners in 1980, is what became, to many, the musical Mecca of Green Street that has spawned reunions and fan pages.

Although Mabel’s closed in 1999 after struggling with changes in the musical landscape, the music and memories live on. “For a small club in a small town, how rare was it that Mabel’s could draw that many bands,” Paul mused, “It was a miracle.”

Photographer Della Perrone covered dozens of shows in Campustown during the 1980s. She recently donated her work to the university’s Sousa Archives and Center for American Music and has generously allowed us to use a few photos for this story. Below Della recalls the Green Street scene for those of us not around at the time:

What was it like to go to Campustown at night for a show? Could you hear the music out in the street?

Yes, you could hear the music in the streets and, if they opened the windows on a warm evening, you could hear it really well. For a big show (someone local and popular or one of the bigger acts) the line to get in would be down the street to the end of the block. Sometimes, they would have to turn people away because the club was at capacity. People were always out on the sidewalks in Campustown back then, especially on a weekend night. It was a party atmosphere.

Can you create the scene of a typical night out (if there was one) in Campustown for us?

First, find a place to park—a challenge even back then. Often, people would meet for dinner somewhere first—maybe Eddies, which was a fun place with great food. Ten p.m. was time to get to the club—maybe 9:30 if you wanted to see the first band. Most bands played two to three forty-five-minute sets with a fifteen-minute break between. On a great night, the crowd would be solid from the stage to the back of the house. Sometimes, we’d find a place to eat after the show or go to someone’s house for an after-hours party.

Can you describe what it was like to be at Mabel’s? What about Panama Reds?

Mabel’s got to the point where the carpeted parts might as well have been waxed – they were so soaked with booze and goop. Of course, people still smoked in bars back then, and they’d just put their cigarettes out on the floor—carpet or not—on a crowded night. Even if management tried, they couldn’t keep up. In the summer, none of those bars’ HVAC systems could keep up if the house was packed. It would get sweltering hot. So sweltering hot, smoky, smelly, sticky floors, and so packed you couldn’t move.

For those who wanted to protest injustice, celebrate a victory, or just carve out a space to perform, Green Street provided the perfect platform. It has reliably served as one of the most public stages to deliver important messages and exact change. We have included a selection of photos that represent the variety of ways Green Street has always supported us.

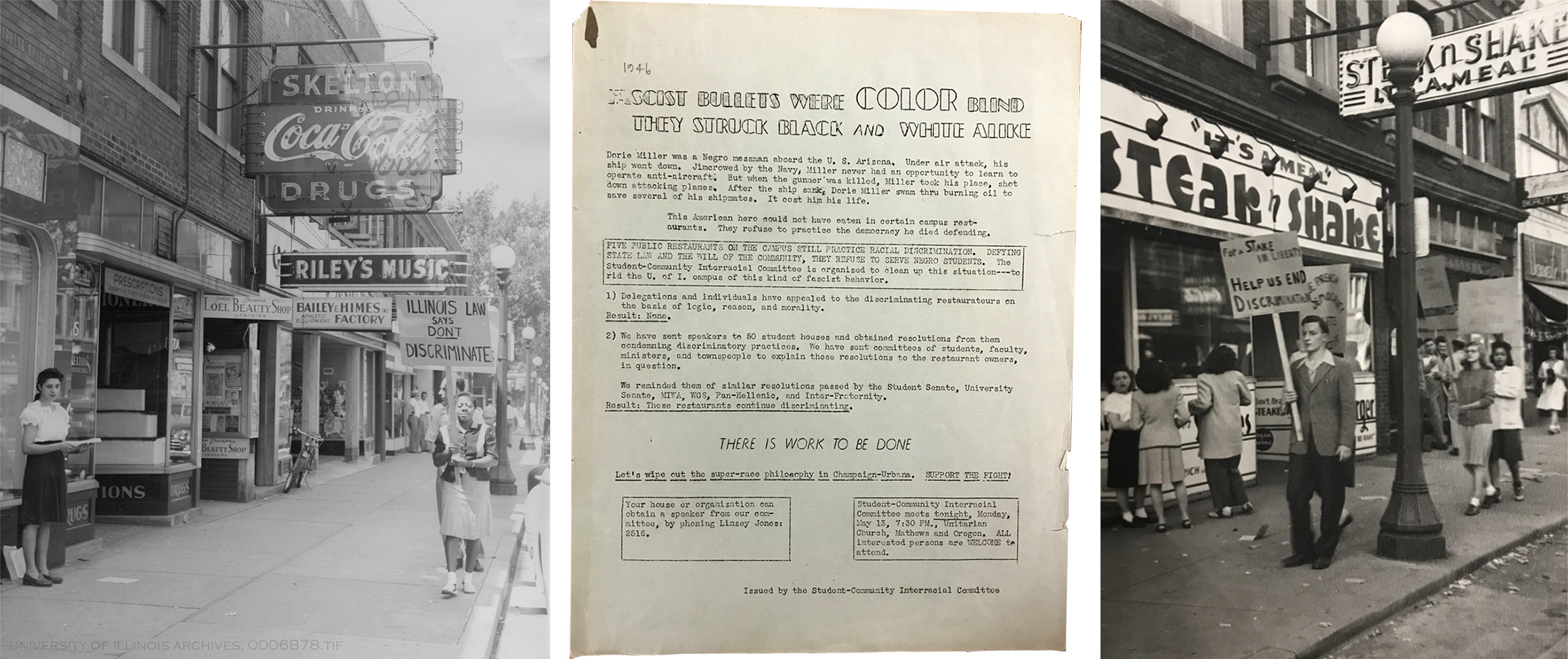

These photographs of students protesting racial discrimination were taken a year after WWII had come to an end. Black and white soldiers had fought the enemy together, but returned to different and unequal American realities. Disregarding Illinois law, some restaurants in Campustown refused to seat black customers. In July of 1946, members of the Student-Community Interracial Committee, frustrated with the injustice, demonstrated in front of places like Steak ’n Shake and Skelton’s Drugstore on the 600 block of Green Street.

You can find out more in Deirdre Lynn Cobb’s 1990 master’s thesis, “Jim Crow Room & Board: The experience of African American Students at UIUC from 1945 to 1955.”

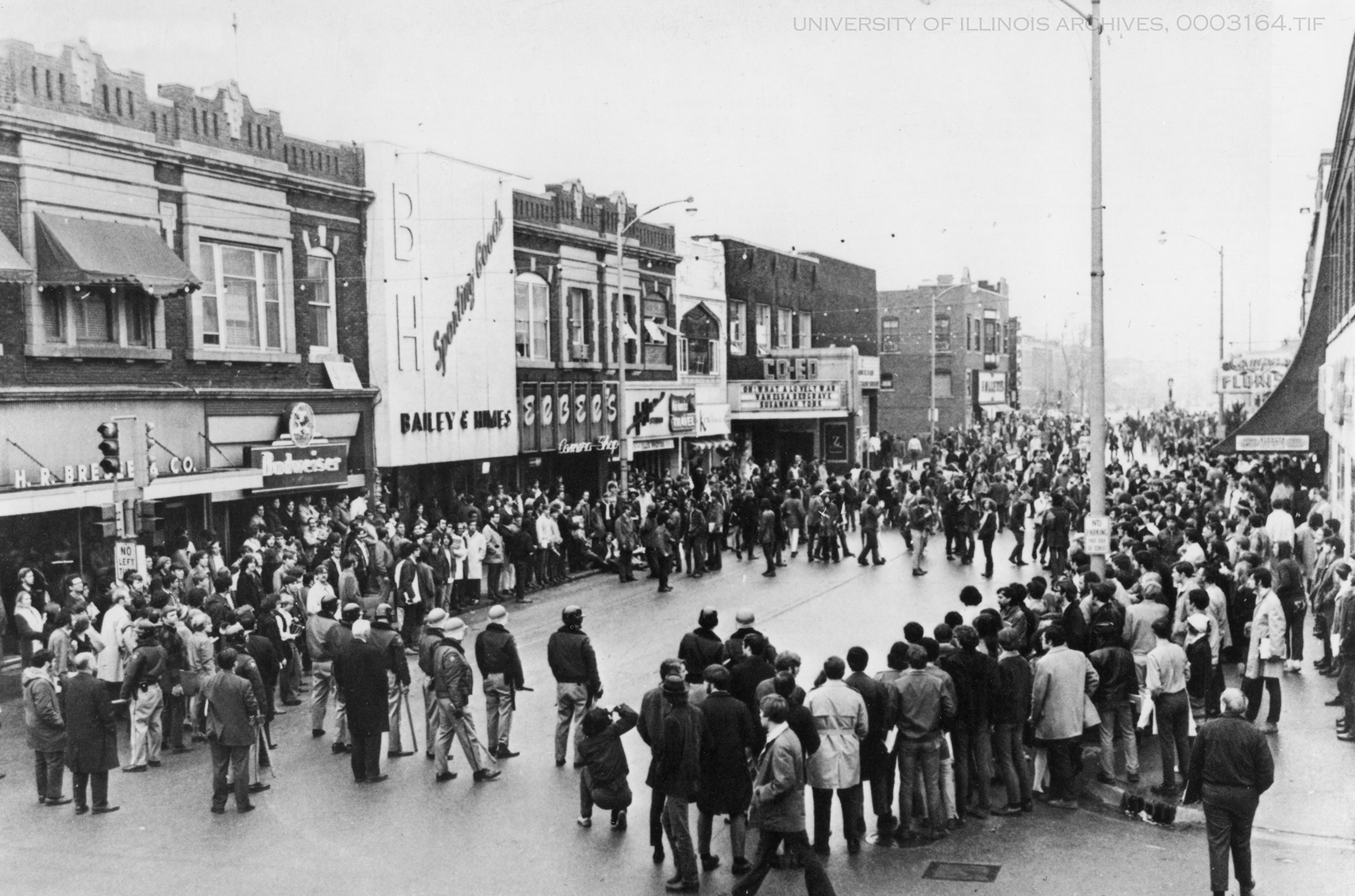

In this photo, which originally appeared in the Daily Illini, students confront the police on Sixth and Green Streets on March 2, 1970. They gathered to protest the campus recruiting by General Electric, a company that was profiting from contracts with the Defense Department during the Vietnam War. Windows were broken and two fire bombs were found in Altgeld Hall. According to the Daily Illini, eight were injured and twenty-one were arrested.

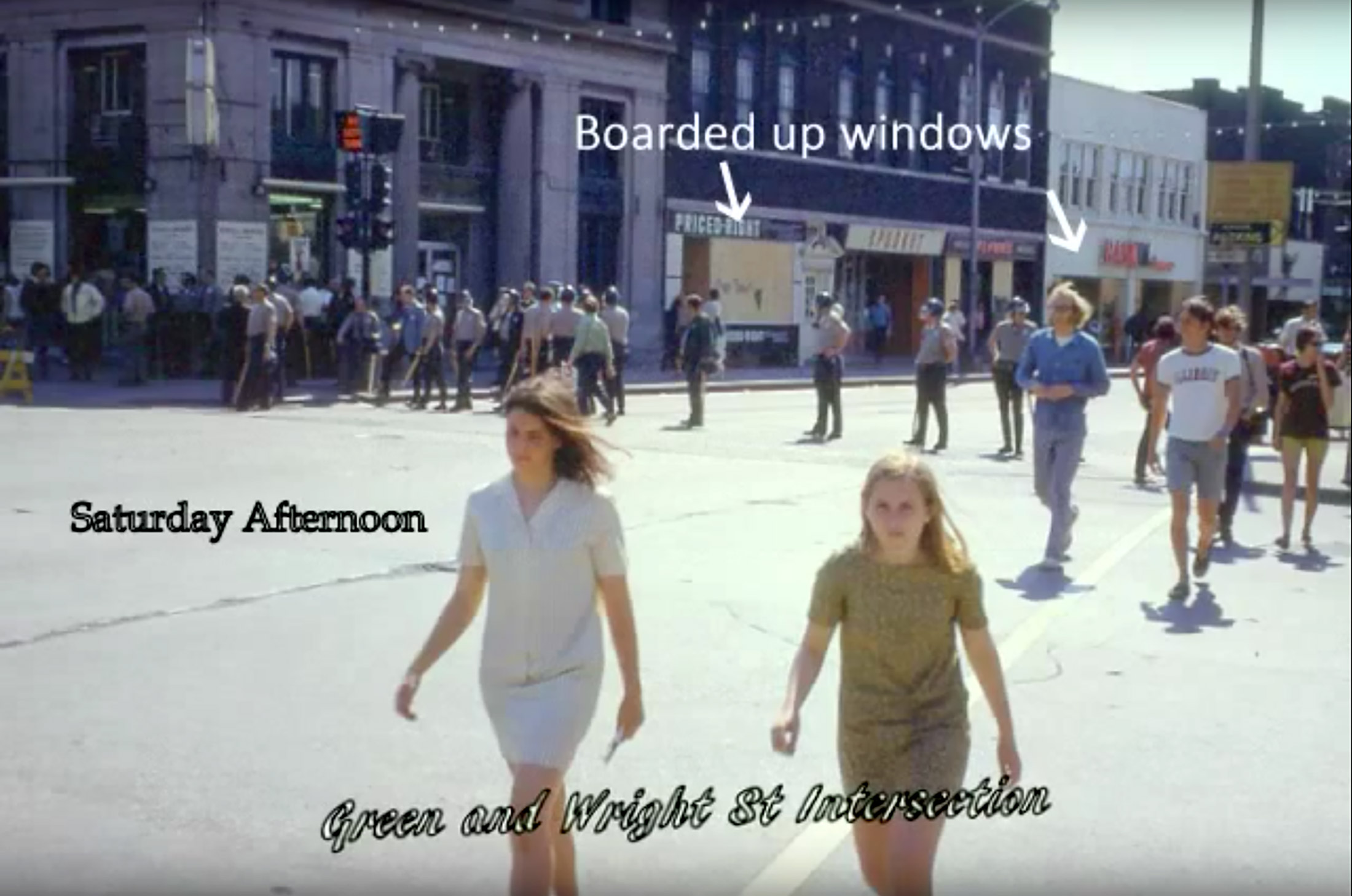

On Saturday, May 9, 1970, Jeff Monroe (ENG ’70), an aerospace engineering senior, grabbed his Argus C4 35mm loaded with Kodachrome, headed to campus, and captured this image at the intersection of Green and Wright streets.

Just a few days before, Illinois, along with universities throughout the country, participated in a nationwide strike to protest the United States’ invasion of Cambodia as well as reaction to the killing of four Kent State University students on May 4. The striking Illinois students charged through campus breaking windows in the Armory, the president’s house, and several businesses on Green Street.

Jeff, who now lives in Cincinnati, remembers the tension of that period and sensed that something big was going to happen. “I guess I thought enough to think it was historical. In this case, I was lucky enough to be in the right place in the right time,” he recalled during a recent phone call. “It was not a good time there.” Almost all of the classes were canceled, and the University called in the National Guard to patrol the campus.

Watch Jeff’s entire video.

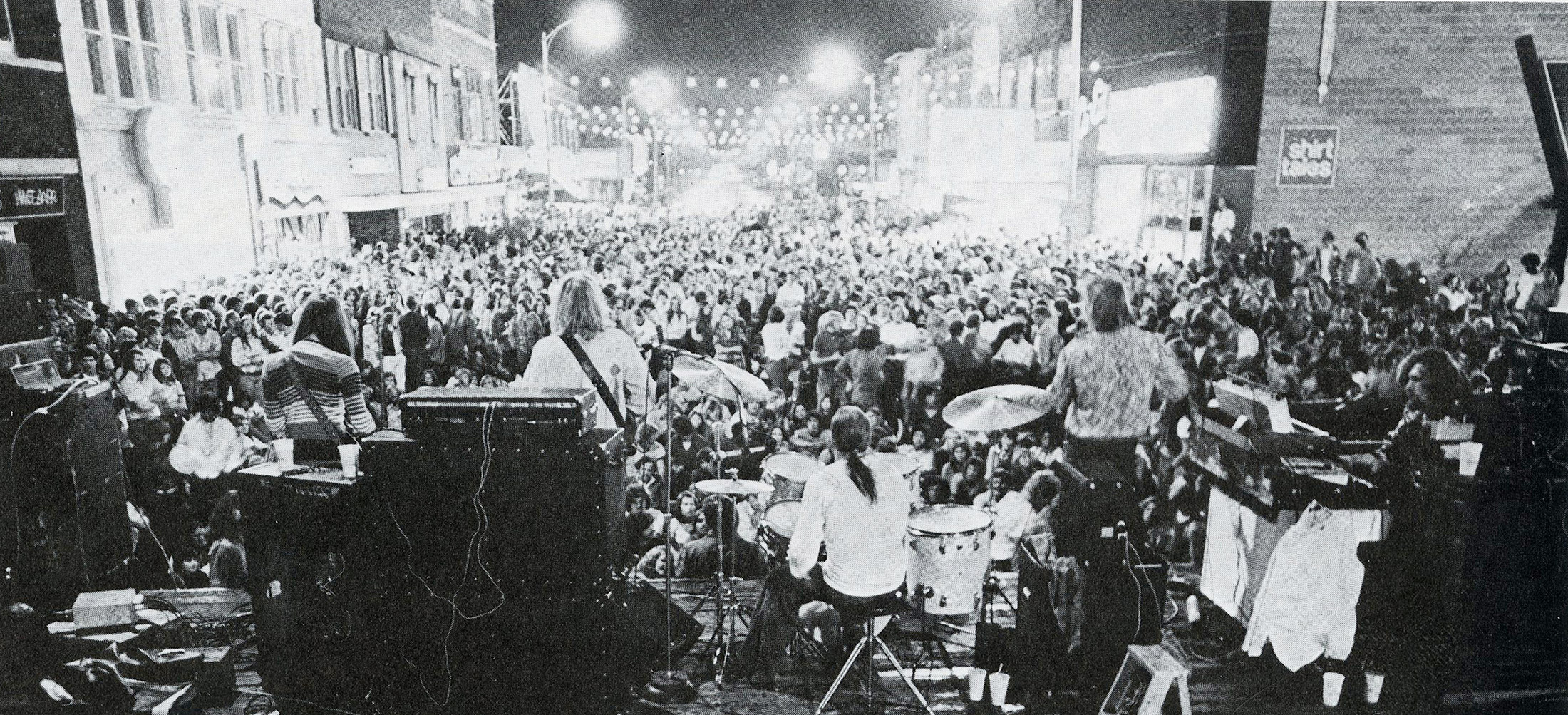

Music wasn’t confined to the clubs and bars that dotted Green Street in the 1970s. Sometimes the patrons flooded the street itself to watch bands perform at outdoor concerts. It was a tradition for bands to play during New Student Week at concerts sponsored by Campustown merchants. This photo was taken on August 22, 1975, when Appaloosa, a popular local country-rock band, took the stage.

“When the ‘walk’ signs turned on at the intersection of Wright and Green streets on Thursday evening, pedestrians flooded into the streets,” wrote the Daily Illini on September 21, 2007. “And then they dropped to the ground. Other protesters traced the outlines of their bodies with chalk as they chanted.”

Four years after the start of what would come to be referred to as the Iraq War, more than sixty demonstrators—which included university and high school students, alumni, and veterans—lay on the ground in protest. Patrick Schmitz (LAS ’06, ’11), took this photo of the demonstrators on Green Street between Wright and Sixth streets. You can see more of his photos of the protest here.

In this image taken on December 2, 2014, hundreds of students marched down Green Street in protest of the August killing of African American Michael Brown by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. Olabode Oladeinde (AHS ’15), president of the Central Black Student Union which organized the event, captured the feeling of many of the people there when he told the Daily Illini: “Police brutality is just something that we need to raise awareness about, because we feel like it’s been going on for way too long.”

The week following the Ferguson march, the Central Black Student Union, Champaign-Urbana Citizens for Peace and Justice, the Graduate Employee’s Organization, and the local NAACP chapter, along with other groups organized a die-in protesting the targeting of African Americans by the police. The demonstrators remained on the ground for more than four hours, the same amount of time Michael Brown’s body lay in the street. Protesters in this image chant and carry signs at the corner of Green and Wright streets.

“This is not an individual issue, those are not individual cases,” Ariana Taylor, a senior and vice president of the Central Black Student Union told the Daily Illini at the time. “This is something that affects all of us. This (demonstration) is a symbol that we are all united and we are in this together. It’s about time that people started shedding light on these types of incidents.”

Almost one hundred years after its heyday, swing dancing still has a spot on Green Street—at the Wright Street intersection, to be exact. In this 2017 photo, Illinois’ Newman Dance Society dashes to the intersection bringing their fancy footwork until the light changes. “We’ve used Green and Wright for the past few years because it is a corner that is very visible and has plenty of space for us to use,” Thomas, a member, said in a Facebook chat. “In addition, it is right in front of the Alma Mater, which is always a nice touch no matter what’s happening.”

It was the win that was felt around the world! You didn’t have to be in Chicago to celebrate the greatest Cubs victory in 108 years. On the night of November 2, 2016, Green Street erupted in celebration after the Cubs defeated the Cleveland Indians in seven games to win the World Series.

No one could have predicted at the turn of the twentieth century that by the turn of the twenty-first century, once quaint Green Street in Campustown would be home to towering apartment buildings visible from the interstate and cater to almost 50,000 undergraduate and graduate students.

Today, there’s little the students in 1919 would recognize on Green Street, save for the cornices at the top of Busey Bank and Murphy’s Pub, visual markers we used as we put this story together.

So, if it helps to digest this selection of photographs—which is in no way meant to be definitive—think of Green Street as if it were a stage that has hosted countless productions and whose scenery has been struck each time a new cast and crew descended.

Some reviews of the changes have been scathing, other laudatory. Yet, for each generation, this is the Green Street on which they shopped, danced, drank, worked, lived, and marched. The one they will remember.

Ray Dames (BS ’92, MCS ‘95, MBA ’95) was finishing up his MBA—and always with his video camera—when a friend asked him to film some footage of a fundraiser for Rwanda that was going on around campus. Through the cracked windshield of his 1989 Mazda, Ray Dames shot this footage of Green Street between Neil and Wright streets in the summer of 1994. We have edited the video to include just the Green Street portion paired with footage filmed in 2019. The twenty-five-year comparison is astonishing. If you’re interested in seeing more of the campus in 1994, you can see Ray’s full video here.

Horse-drawn carriages were still sharing the road with early automobiles shown in this image thought to be taken in the 1910s (there is even a bicycle resting against the curb in front of Mead’s Cafeteria). The early part of the twentieth century saw exponential growth in American auto. In 1910, Ford produced 32,000 vehicles; by the end of the decade over 820,000 Fords rolled off the production line. The Leseure Brothers Billiard Hall remained in this location for more than twenty years, when, in 1938, the Co-Ed Theatre was constructed in its place.

An abundance of trees shaded the intersection of Green and Wright in this photo, dated 1922, decades before Alma Mater ultimately anchored the corner in 1962. The Green Tea Pot was run by the women of Delta Gamma who opened the shop as a way to raise funds for a new sorority house. After the first year, they had raised enough for a down payment. Delta Gamma students still reside in the same Nevada Street home decades later. Several other businesses are visible, including Duncan Studio, Mosi-Over, and Twin City Cafe.

Like any small-town main drag, Campustown’s Green Street had a barber shop (Kandy’s), a drug store (U of I Drugstore) and the Five and Dime. In this photo taken in the 1950s, Follett’s Bookstore occupied the storefront later occupied by Zorba’s. It moved across the street to the northwest corner of Wright and Green in 1962.

While the block between Sixth and Wright remained largely retail over the years, looking west down Green Street, just beyond Prehn’s, you can see the street was lined with residential homes, including more than a dozen fraternities and sororities. Some of these are visible in this photo. Over the years, most of these homes were torn down to make way for new retail buildings and student apartments. In 2013, construction for a multi-million-dollar apartment complex revealed one of these houses, 509 ½ West Green Street, tucked behind a 1950s retail façade.

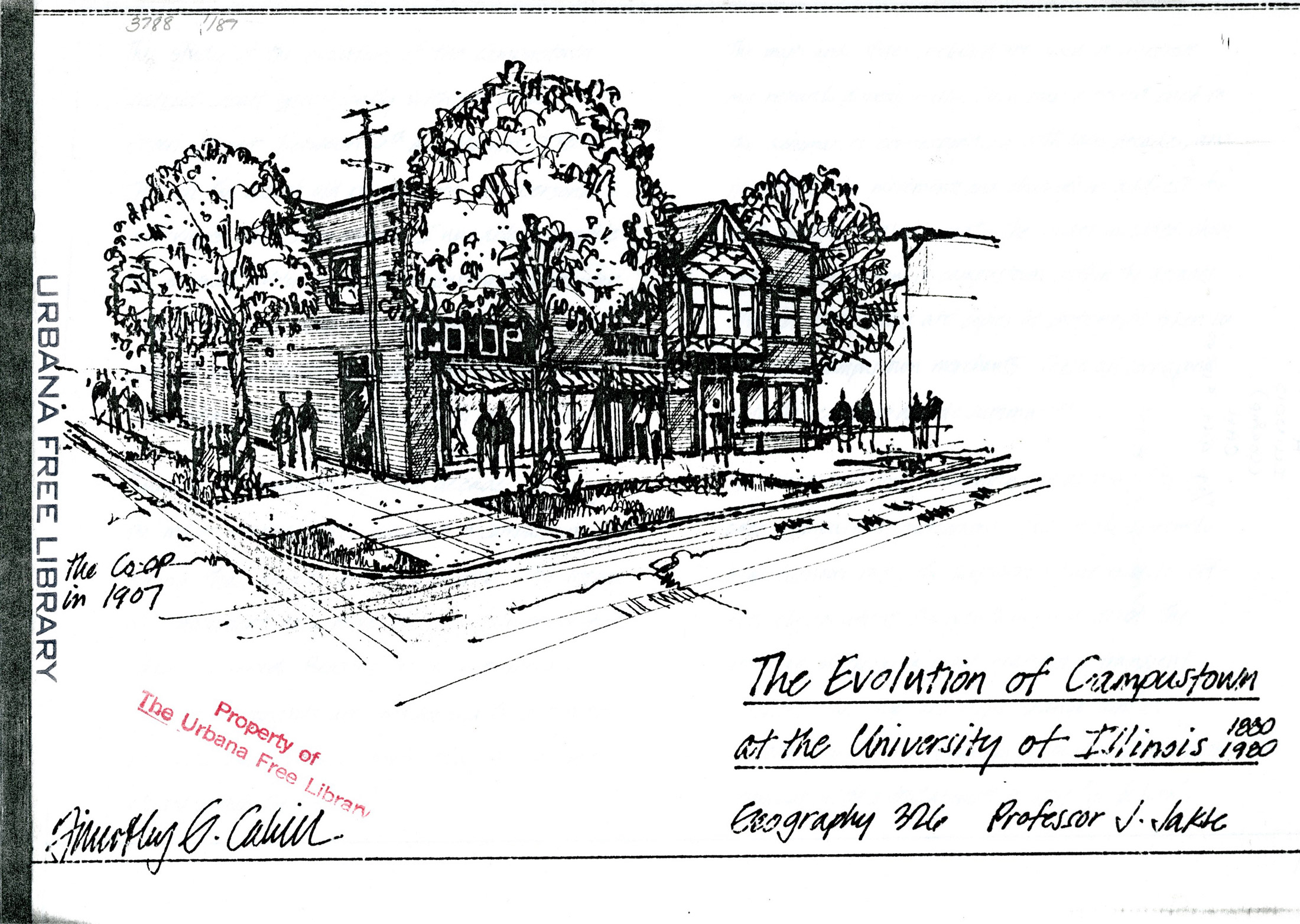

This is an image of the title page of a project Timothy Cahill (MA ’80) created when he was pursuing a master’s in architecture in 1980. Within the bound book—which was donated to the Champaign County Historical Archives—is a detailed examination of the development of Green Street between Wright and Sixth streets from 1860 to 1980. Even in 1980, he remarked on how frequently the businesses changed and the dearth of photographs. In many ways, his project from almost forty years ago, helped us assemble ours. He writes: “Due to the extremely high turnover rate, the shop owners have failed to effectively document the growth of this district. The attitude of this area is geared to a transient clientele, the shops and people change almost completely unnoticed. Changes in society reflect in the vernacular, as the district attempts to ‘stay in fashion’.”

We spoke to Timothy on the phone recently, and though he now lives in Missouri, he still has a number of reasons to come back to visit. He is the lead architect at HNTB, the firm that designed the new Henry Dale and Betty Smith Football Center, as well as previous additions to Memorial Stadium.

Long before online shopping became ubiquitous, independent bookstores and record stores thrived on Green Street. Students could wander the nooks and crannies of Babbitt’s and Acres of Books or discover hidden treasures at Record Service. In 1969, Record Service started out as a student organization, purchasing albums for students at discounted rates. In 1971, it moved into a Green Street storefront and was run as a collective. At one point, there were well over a dozen employee-owners. Phil Strang, one of the co-founders, remained and ran the store until it closed in 2003.

Green Street storefronts located on the first floor often contended with water overflowing from Boneyard Creek, which ran behind the many businesses that sprung up on the street. The creek’s flow had been manipulated over the years and these two images, taken in 1980, show just how bad the problem had become. It wasn’t until Champaign addressed Green Street’s flooding problem through a number of methods, that the high-rise developers in the 2000s would even consider such ambitious projects.

The owner of Campus Florist, Anne P. Johnston, saw neighboring businesses come and go and yet, for more than seventy-seven years, her business thrived. Anne, originally from Chicago, came to Champaign to attend the university to study floriculture. While still going to school, Anne snatched up the 609 Green Street location in the early 1940s from two men who were called to serve in World War II. Out went Westcott’s Men’s Furnishings and in its place, what was to become a veritable Campustown landmark. (She ultimately left school at the urging of the head of her department. He explained to Anne’s mother, who was in Champaign for a visit, that she was where his students would be ten years from now.)

In a recent phone call, she clearly remembered those days when there were very few cars on campus, breakfast at the Union was 25 cents, and dances were held every weekend. “At one time we had a lot of dances on campus and they all bought flowers for them,” Anne recalled. “Fellas always bought flowers for the girls. Now the girls buy their own or they buy flowers for the guys.”

In October of last year, Anne closed the shop lamenting the planned 17-story apartment building that is being built two doors down. The commotion and the construction in the shared alley proved to be too much. Yet, her fondest memories are of the people she met. “I met people from all over the world, all over Illinois. Even parents would come back in with their kids and tell them they worked there that’s how they got through school.” Anne paused. “That was quite memorable.”