Doris Derby (LAS ’75, ’80) stands in the bright sun at the foot of a wooden porch in rural Mississippi in 1968. Her lens is trained on a woman in a short-sleeved dress and saddle shoes as she hangs laundry. A striped child’s t-shirt dangles from wooden clothespins. White sheets catch the wind, and a Barq’s root beer sign peeks through a broken window.

The woman’s face, partially obscured by shadow, reveals no emotion. She appears neither happy nor sad, just a solitary figure performing a routine, domestic task. Even the clothing pinned to the line offers only a few clues. Where is the little boy who wears that shirt? Who lives in the household with her?

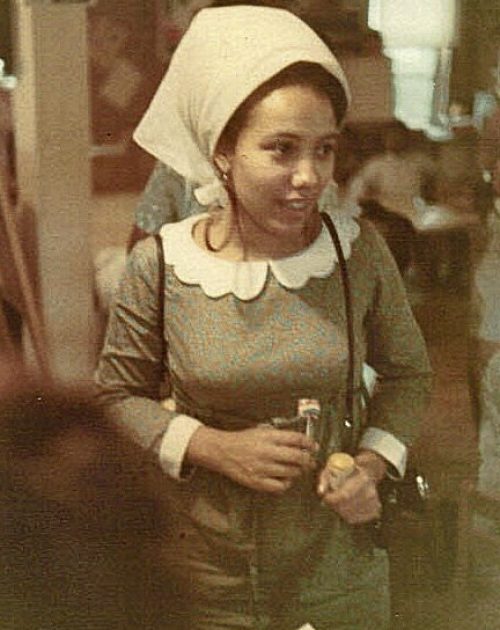

By the time Derby takes this photo, she has been in Mississippi for five years. She’s an adult literacy programmed instruction teacher for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Bob Moses, SNCC’s Mississippi leader, recruited her shortly after she graduated college in 1963 when she was teaching elementary school in Yonkers, New York. This photograph is one of thousands that Derby took in the 1960s and early 1970s when she worked in the South with SNCC and Southern Media, Inc., an organization committed to documenting the Civil Rights Movement.

When she stands at the foot of this porch with her camera, it has been just five years since Derby attended the funeral of four girls murdered in Birmingham, Alabama. Although Derby grew up in New York, she is compelled to be here—at this place, at this time—to bear witness to the Civil Rights Movement.

Derby’s photographs capture small, private moments but carry the weight of the momentous groundswell of change for a people who wanted and deserved better. These two women, on either side of the camera, represent facets of the struggle: one whose life is shaped by segregation in the South, and one whose mission it is to humanize the movement.

During her time in the South, Derby hones her craft, drawing inspiration from another black artist, Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava, famous for his images of everyday black culture in New York City.

Each image Derby creates depicting life for blacks in the segregated South contributes to the narrative that propels the Civil Rights Movement. Her desire to record history as it unfolds has roots that reach far into Derby’s family line, where art and activism are valued.

✦ ✦ ✦

Derby stands in the basement of her family’s home in the 800 block of 224th Street in Williamsbridge, a neighboorhood in the Bronx. Sawdust covers the floor, and leftover wood cuttings sit in a pile near her father’s woodworking bench. She is a little girl in a country recovering from World War II. A country that fought oppression overseas, but still prevents her father Hubert Derby, a civil engineering graduate from the University of Pennsylvania, from getting a decent job in his field because he is black.

Hubert goes beyond just making do. He works for the New York State Employment Service and is one of two urban farmers on the block. To earn extra money, he has a cabinet-making business on the side.

This racially and culturally diverse neighborhood in the Bronx is a place that envelopes Derby with art, poetry, dancing, and music. When Derby and her older sister, Pauline, are in elementary school, Hubert gives them each a Brownie camera to record their journeys. She remembers her father attending every family event with his camera in hand. He passes along that passion for preserving moments in time to his two daughters.

She is encouraged to create in other ways too. At first, scrap wood in the basement becomes her canvas, filled with painted images. Then her mother, Lucille, teaches her to sew, which leads her to make her own clothes, especially for the holidays. Lucille also enrolls Derby to ballet and tap dance classes, a passion that stays with Derby her whole life.

“I think that the painting, from a visual perspective, and the photographs, went hand-in-hand. I developed my painting by studying people, particularly black people and families, especially women and children. I later translated that into photography,” Derby says.

This creative outlet is paired with her drive to help. As the granddaughter of the woman who, with her eldest son, who became the chapter’s vice president, and a small group of African Americans, founded the NAACP chapter in Bangor, Maine in 1920, Derby grows up with a profound appreciation of what black Americans still face and the ways that change is possible.

✦ ✦ ✦

Derby spends her first years with SNCC teaching and continuing to create art in an open studio space at nearby Tougaloo College. It is not until 1966 that Derby begins taking photographs in earnest, when two men she becomes acquainted with form Southern Media, Inc.

They invite her to participate in documenting everything she can that is happening in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. Derby is especially interested in the experiences of women and children and the grassroots initiatives of the local communities.

At this point, she feels her training in photography truly begins.

Her images are powerful. Derby’s intimate photographs provide contrast to the images of protests, demonstrations, funerals, and murders that dominate the front pages as the Civil Rights Movement unfolded. Her photographs serve a different purpose. They appear on posters, brochures, and leaflets and communicate directly to black communities the ways in which the Civil Rights Movement is working toward creating change and instilling black agency.

“I wanted to show who the people are, where they lived, and what they were doing. They were the basis of the success of the Civil Rights Movement,” Derby says. “Many activities and initiatives, including forming cooperatives, were a part of that whole movement. Anything you did to challenge the status quo was considered political.”

“Outsiders often see those who are out there protesting, meeting with officials, or scenes from a tragedy—which all are very important. But not everybody was involved outwardly in that part. My focus was to document black people who were engaged in the struggle for equality and justice for all. To depict the life-giving force of the black community keeping on. Even though they face poverty and injustice, they’re surviving, they’re living.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Bundled in a long black coat, Derby shuffles through Krannert Art Museum in mid-October. She looks around eagerly and marvels as she tours the new installation devoted to art created after 1948.

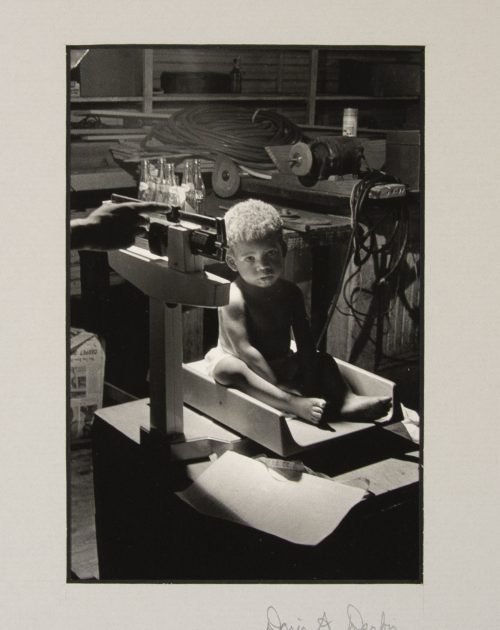

“Oh, here it is,” she says, approaching the photograph to her left as if she were meeting up with an old friend. She smiles and stares at the image of a young boy sitting on a scale in a cluttered, dusty barn.

The child stares back at Derby, his head illuminated by sunlight as a caretaker’s hand adjusts the scale. Empty glass Coke bottles and power chords lay on top of machinery behind him in this makeshift examining room in segregated 1965 Mississippi.

“This picture right here,” Derby explains, “was a child being checked out before attending the Head Start Program at a time when so many children had never had medical exams before nor the opportunity to have a Head Start center in their community.”

The image is a portrait of hope and progress and speaks to the work of organizations like SNCC, the Child Development Group of Mississippi and Mississippi Action for Progress, two initiators of Head Start in the state.

It’s been forty-seven years since she left Mississippi for Illinois to pursue a master’s and Ph.D. in anthropology. When she arrives in 1972, she joins her friend Kay Prickett, an employee of the university, who, with her brother Charles O. Prickett (’70, ’72), worked in the Southern Freedom Movement with Derby. Once here, Derby carves out a life filled with the pursuits she has always sought. Max Roach concerts, dances, dinners at with her African and Afro-Caribbean friends. She becomes a member of campus organizations and frequents the African American Cultural Center. Even during her years at Illinois, she still has “some pieces of my past up here.”

And while she has since made her home in Georgia, with husband Bob Banks, she has never lost her connection to Illinois. Her work is exhibited in galleries throughout the world, and now Krannert Art Museum is the permanent home of four of her images. Also, she has donated her extensive basket collection from Charleston, South Carolina and West Africa to the Spurlock Museum, where Derby was an assistant curator/graduate assistant back in the day.

“When I came here, the University of Illinois embraced me in terms of my interests and my values,” she explains. “I see this as the home for the kind of things I value.”

From an early age, Derby learns the significance of documenting lives through photography and the importance of shared struggle and resilience.

These experiences contribute to her lasting imprint on the Civil Rights Movement, and ultimately, the movement’s imprint on her.

“I knew I was making historic photographs,” Derby says. “I knew I was building this for the future.”