Our campus is home to what now numbers in the millions of collected, created, donated, and unearthed objects from all over the world that are part of the university’s permanent collection. These treasures have been amassed through the hard work and generous philanthropy of countless students, researchers, professors, alumni, and friends.

This occasional series uncovers and discovers the fascinating stories behind these curiosities—from items that reflect our natural and cultural history to art collections that represent all eras and mediums to the endless bounty of riches found in our library alone, including rare manuscripts, maps, and books.

These materials (displayed in museums and glass cabinets, tucked safely in boxes and drawers) are used by researchers as well as by instructors in classrooms and they do nothing less than tell the story of our collective humanity.

In this installment of Curiosities, we pulled from three significant literary collections at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. We dove deep into the papers of Gwendolyn Brooks, Marcel Proust, and Carl Sandburg and found some items that provided our authors with not only sustenance but also celebration.

Hosting in Bronzeville

Hosting in Bronzeville

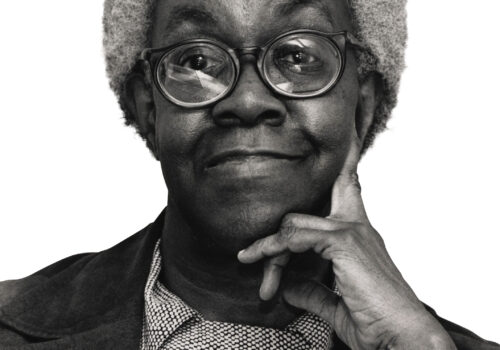

Gwendolyn Brooks was among the most important writers of the twentieth century and spent most her life living on the south side of Chicago. After being the first Black writer to win the Pulitzer Prize (in 1950), she served as Poet Laureate of Illinois from 1968 until her death in 2000.

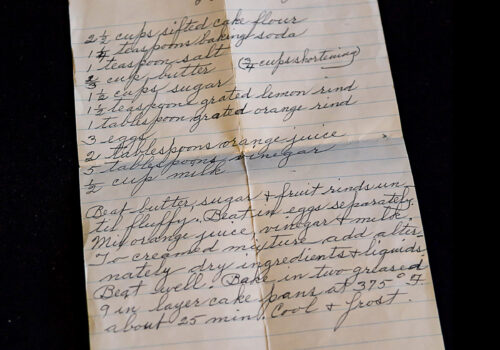

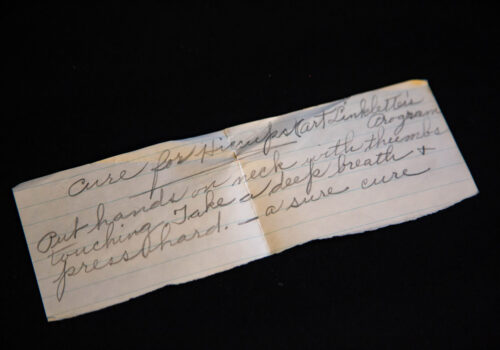

Our Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML) acquired Brooks’ papers in 2013. Part of the collection included a small wooden box marked “recipes.” It is a mid-century version of a Pinterest board, stuffed with recipes and household tips, some clipped from magazines, some handwritten in her careful, flowing script. This recipe for orange cake was tucked inside.

In 2017, in honor of what would have been her 100th birthday, the RBML hosted a party and had a local bakery recreate her orange cake. Everyone loved this perfect party cake, and the library fielded tons of requests for the recipe.

Parties played a large role in Brooks’ life, connecting her with an active circle of writers in Chicago. They met often, throwing large and joyful gatherings. In her memoir, she remembers she hosted her “best parties” in a two-room kitchenette at 63rd and Champlain. One was in honor of Langston Hughes, where “we squeezed perhaps a hundred people into our…party. Langston was the merriest and most colloquial of them all. ‘Best party I’ve ever been given!’ He enjoyed everyone; he enjoyed all the talk, all the phonograph blues, all the festivity in the crowded air.”

The view from this small apartment above a real estate agent and next to the El tracks was fodder for her writing. “If you wanted a poem, you had only to look out of a window. There was material always, walking or running, fighting or screaming or singing,” she wrote.

Savoring a memory

Savoring a memory

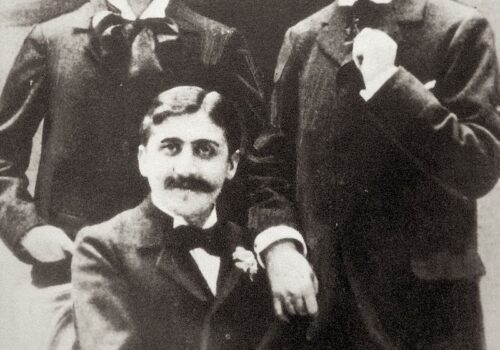

Those who are familiar with the work of Marcel Proust perhaps have always known he had a sweet tooth, literally and existentially. He devoted thousands of words in his most revered work, Remembrance of Things Past, to the madeleine, a scalloped shaped sponge-cake about the size of a walnut. The pastry served as a portal into a journey of involuntary and voluntary recollection of the narrator’s memory. “The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it,” Proust wrote.

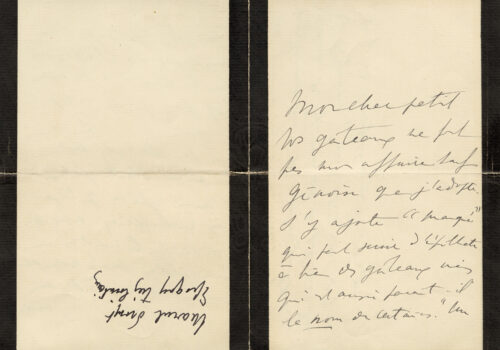

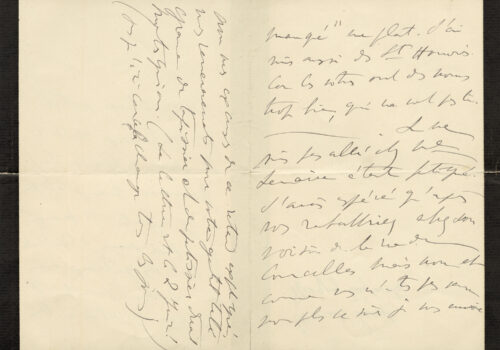

That book was actually composed of seven volumes, published between 1913 and 1927. Yet, almost ten years earlier, he wrote to a good friend inquiring about a different pastry in a letter preserved in the RBML, which is home to one of the largest existing collections of original Proust letters.

“My dearest boy, your cakes don’t do the trick,” Proust began. What followed was a critical evaluation of which cake would accurately capture the reader’s imagination in his forthcoming 1905 essay, Days of Reading.

Caroline Szylowicz, Kolb-Proust Librarian and Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, sees the connection between this essay to Proust’s masterpiece.

“That’s the starting point for reminiscences and evoking back these childhood vacations in the countryside,” Szylowicz explained. “And this is the same setting that you will find again a few years later, in the first part of Remembrance, where the narrator as an adult, drinks a cup of tea, in which he keeps a little piece of madeleine.”

Ultimately, the back and forth between Proust and his friend resulted in just one but very memorable sentence in his essay.

“Some of those cakes in the shape of towers, protected from the sun by a shade—‘manqué,’ and ‘Saint-Honorés,’ and ‘gênoises,’ — whose lazy and sugary fragrance has remained mingled for me with the tolling of the bells for high mass and the gaiety of Sundays.”

Crumbling Past

Crumbling Past

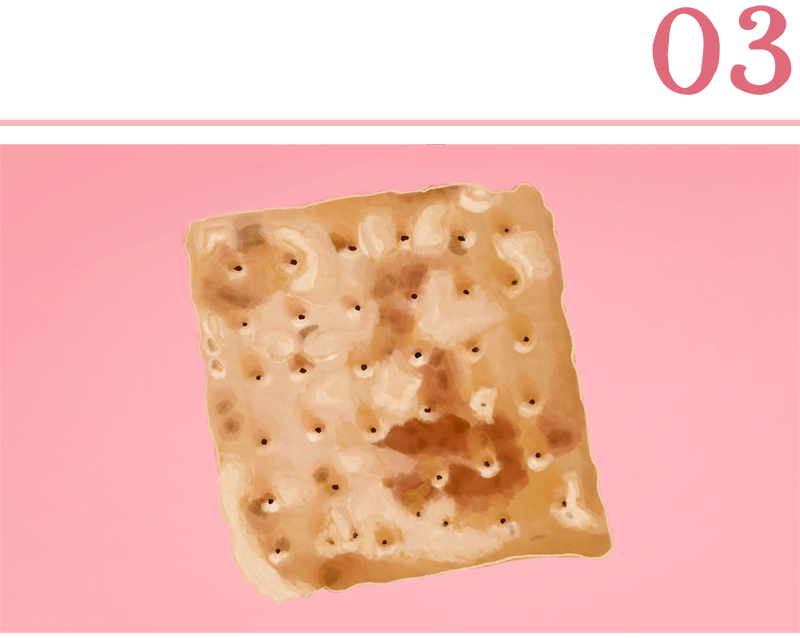

Crumbs, sealed in a small plastic bag, share an archival box with a black visor, a broken pocket watch, and buckeye nut, having nothing more in common than their onetime owner, three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Carl Sandburg. The Rare Book and Manuscript Library recently acquired these random contents to add to its already comprehensive Carl Sandburg collection.

Ruthann Miller, visiting curator at RBML, examined the yellowed crumbs, once catalogued as “three dried bread cubes,” and drew a connection to Sandburg’s longtime fascination with Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. Miller believes the crumbs are the remnants of hardtack, a hard, non-perishable, cracker-like food made of flour, water, and salt that was rationed to soldiers in the Civil War.

“He was a huge Civil War buff,” Miller said. “It would have been something he would have collected and kept.”

Sandburg would likely have been issued hardtack when he served in the Spanish-American War in 1898—just like the Civil War soldiers he wrote about later in life. Hardtack is so durable that the Army kept stores of it for years. In fact, some of the hardtack Sandburg’s fellow soldiers were served could have even been left over from the Civil War that had ended thirty-three years before.