Our campus is home to what now numbers in the millions of collected, created, donated, and unearthed objects from all over the world that are part of the university’s permanent collection. These treasures have been amassed through the hard work and generous philanthropy of countless students, researchers, professors, alumni, and friends.

This occasional series uncovers and discovers the fascinating stories behind these curiosities—from items that reflect our natural and cultural history to art collections that represent all eras and mediums to the endless bounty of riches found in our library alone, including rare manuscripts, maps, and books.

These materials (displayed in museums and glass cabinets, tucked safely in boxes and drawers) are used by researchers as well as by instructors in classrooms and they do nothing less than tell the story of our collective humanity.

In this installment of Curiosities, we are focusing on three special spots on our campus that feature glass.

Shaping science

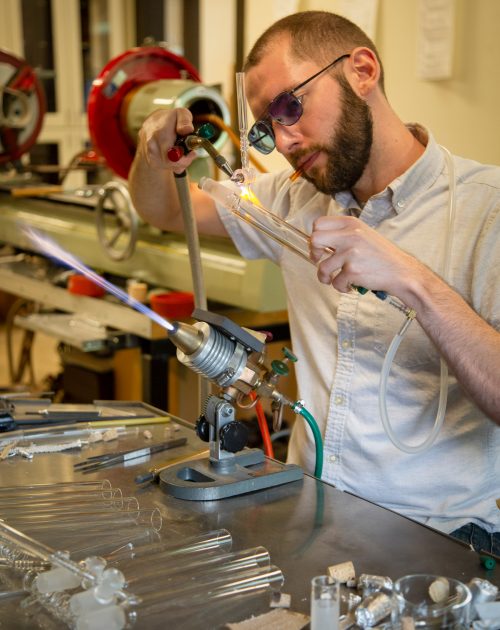

It is refreshing to know that in the era of the supply catalog and the purchase order, there are still pockets of industry where materials are handcrafted. Scientific glassblowing is one of those industries, and Andy Gibbs is one of those artisans.

The School of Chemical Sciences glass shop is located in Noyes Lab, and when I enter, Gibbs warns me not to put my bag down on the ground. “There’s a lot of broken glass around here,” he says. In truth, his shop is tidy and the only broken glass I can see is lined up on counters, waiting to be repaired.

In addition to repairs, Gibbs also creates custom scientific glassware. He draws on his love of science and his engineering background when he meets with researchers to work through their needs and design the right vessel for their experiments. “I really love scientific work because there is a lot of problem solving involved,” he said.

On one end of Gibbs’ shop, rows of drawers line the wall, filled with the glass components he uses in his work—standard glass tubes, stoppers, valves, and joints. Two torches sit on his stainless-steel desk, the flames dancing between white and blue and orange, depending on the temperature. One is secured to the desk; the other torch is hand-held. “From a glassblower’s perspective, anything under 1,000 degrees is dangerously cold,” he explains. “My goal is to keep the entire work area of the glass at least above 1,000 degrees and as high as 2,300. That is the temperature the glass is at when it has the consistency of honey.”

Using the heat, Gibbs can change the tube’s shape, attach two pieces together, and repair cracks in the glass. He blows air into the glass through a thin plastic tube, similar to medical tubing, that he holds in the side of his mouth. By creating small bubbles in the liquifying glass, he can create holes and then connect additional tubing or valves as needed.

Illinois has employed glassblowers for decades, but today Gibbs is the only one at Illinois. In fact, only two universities in the state employ scientific glassblowers: here and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“Having somebody on campus who knows about the material properties—what is easy, what is difficult, or what is not really possible—makes it easier for the researchers. Not everyone comes to me knowing what they are looking for, and part of the service I offer is helping them decide what the most practical solution is,” he says. “People are often surprised to find out how much of this has to be done by hand.”

Gibbs first got into glassblowing as an art, and finds that his day job informs his artistic creations. “Whether I’m here or at a private studio doing personal work, I like knowing that the things I make are going to be used by a person,” he says. “Cups are my big thing right now. I always encourage people, don’t put it on display. Use it. And if you break it I’ll make you another one!”

Walking on glass

“The stack floors in Altgeld Hall upstaged the books on that very first visit, for the floors are made of glass,” wrote Henry Petroski in a 1999 article for American Scientist.

Petroski (GRAINGER ’64, ’68), currently a professor of civil engineering at Duke University, is far from alone in his admiration of Altgeld Hall’s Mathematics Library’s glass panel floors. The floors are a popular stop during campus tours of Altgeld.

“People like to come in, and they like to walk on the glass floors,” Becky Burner, senior library specialist said smiling. “The stacks are open to anyone.”

The floors were part of the original construction when Altgeld Hall—originally dedicated as Library Hall—was built in 1897. The light cast from the gas lamps and large windows reflected off the transparent ceilings and floors provided much needed light in a pre-electrified era.

The glass panels’ strength and endurance through the decades owes quite a bit to the overall design of the Altgeld stacks themselves.

“Rather than the bookcases being supported by the floors, as I had previously assumed was the way all stacks were constructed,” wrote Petroski, “the floors in Altgeld Hall are clearly supported by the bookcases.”

The library was expanded in 1914 and additional glass floors were added. Yet, even though more than one hundred years of scuffs and scratches are etched into their surfaces, only a few panels have had to be replaced—unfortunately by plywood, as the price of the glass proved to be too costly.

Reflecting history

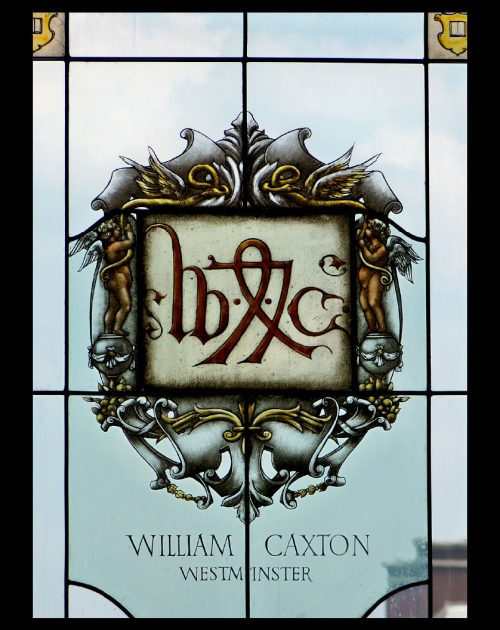

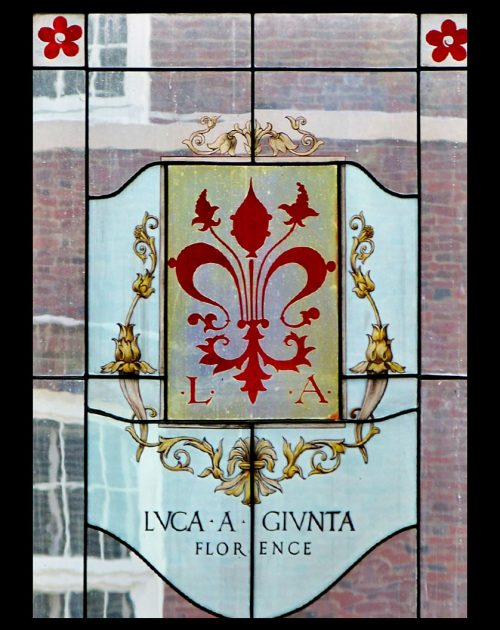

There are countless beautiful spots on our campus, and the Main Library’s second-floor reading room ranks among the grandest. The ceiling rises to an impressive twenty-eight feet, and a sea of solid wood tables and chairs fill the room.

This portion of the library was built in the 1920s, and during its construction, then-librarian Phineas L. Windsor commissioned twenty-seven stained glass windows to line the perimeter of the room. Each window measures eight-by-sixteen feet, and depicts a different printer’s mark dating back to the Renaissance.

Shortly after the introduction of the printing press during the 1400s, European printers created identifying marks as a kind of trademark. These ornate marks were often printed on the title page of books to distinguish printer’s works from one another.

The windows in the Reading Room represent printers from across Europe whose early forays into book publishing helped expand the reach of knowledge. The Rare Book and Manuscript Library holds copies of early works printed by each printers’ mark represented.

This story was published .