Our campus is home to what now numbers in the millions of collected, created, donated, and unearthed objects from all over the world that are part of the university’s permanent collection. These treasures have been amassed through the hard work and generous philanthropy of countless students, researchers, professors, alumni, and friends.

This occasional series uncovers and discovers the fascinating stories behind these curiosities—from items that reflect our natural and cultural history to art collections that represent all eras and mediums to the endless bounty of riches found in our library alone, including rare manuscripts, maps, and books.

These materials (displayed in museums and glass cabinets, tucked safely in boxes and drawers) are used by researchers as well as by instructors in classrooms and they do nothing less than tell the story of our collective humanity.

In this installment of Curiosities, we examine our connections to three films regarded by many to be landmark contributions not only to their genre, but to the entire filmmaking canon. As Roger Ebert (MEDIA ’64), our movie-critic alum used to say, “we’ll see you at the movies.”

Storyboarding GOAT

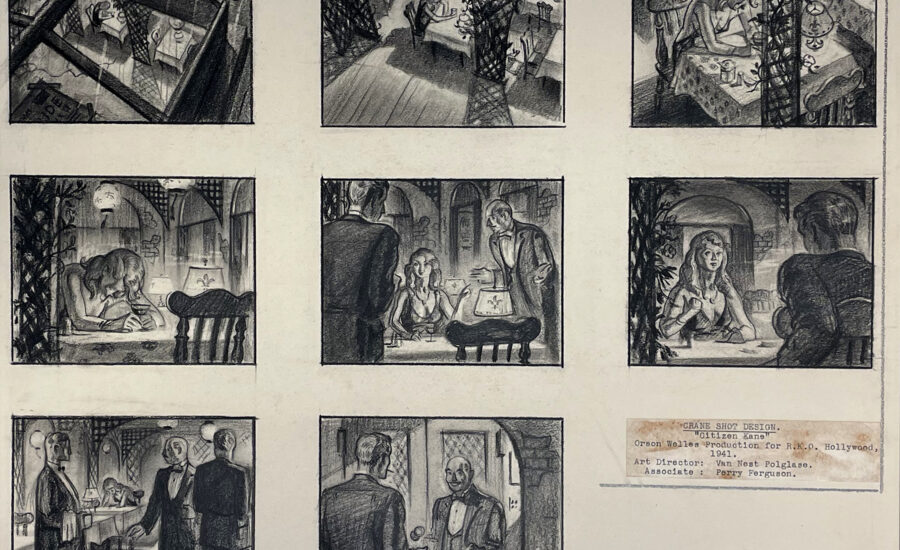

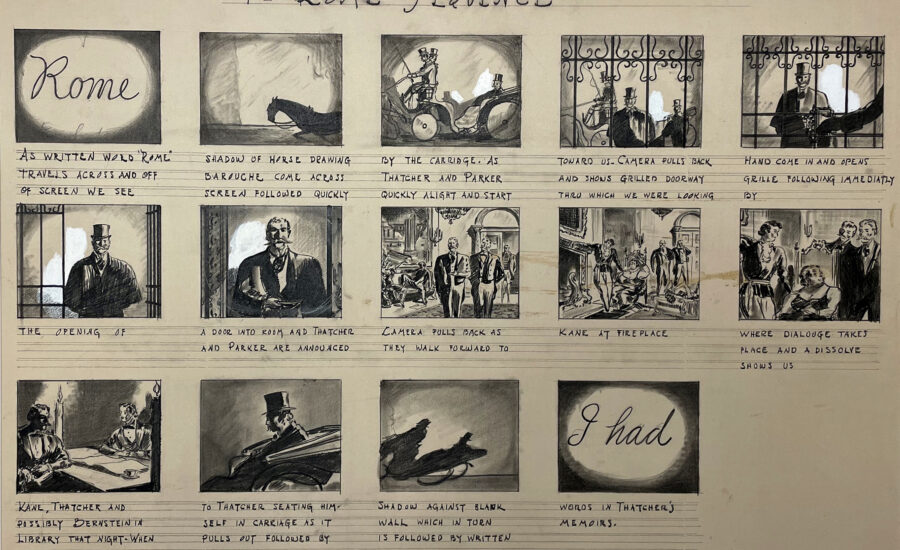

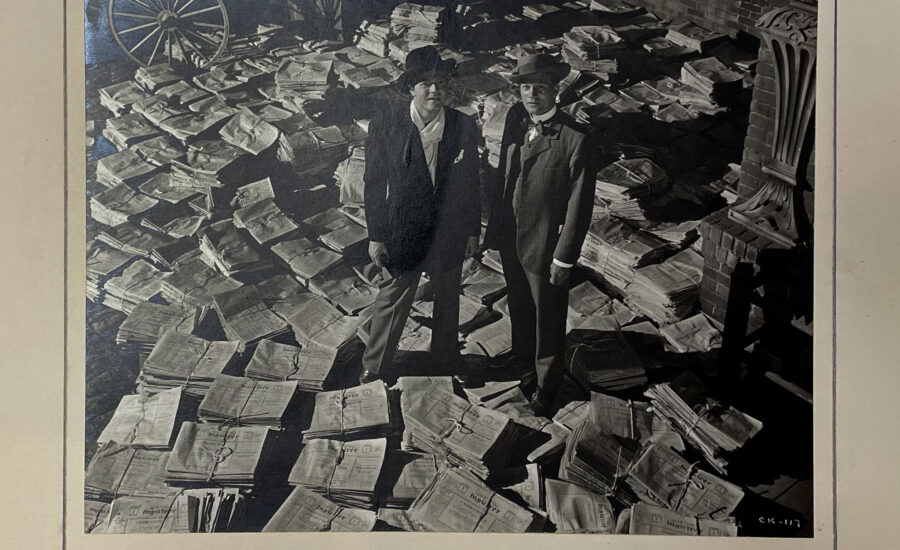

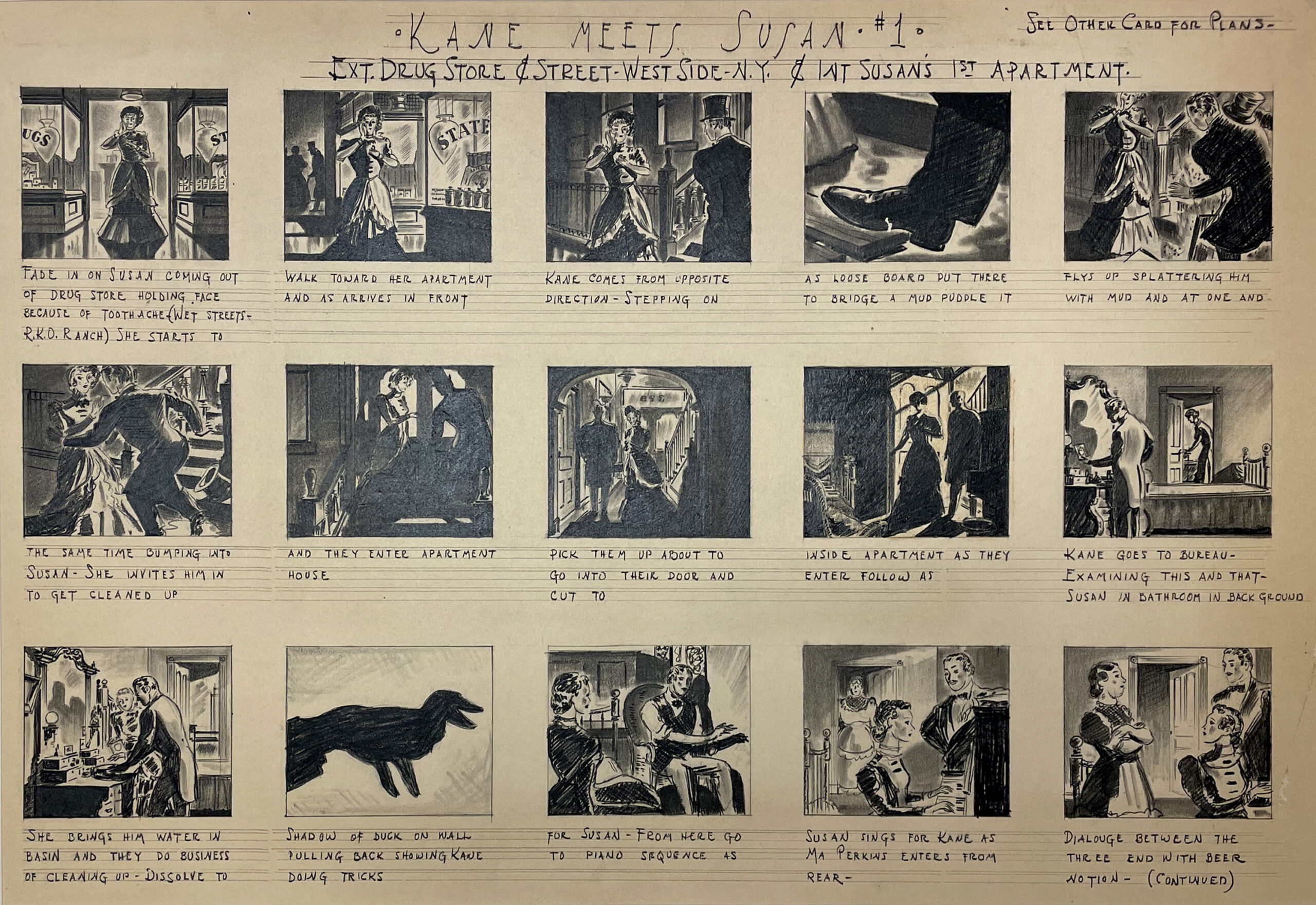

As I examined the Citizen Kane storyboards in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I kept thinking about the recent documentary, The Beatles: Get Back, about making the Let It Be album in 1970. Watching the Fab Four struggle to create classic songs we all know so well was not unlike reviewing the visual drafts of a Citizen Kane that wasn’t yet made.

The movie produced, co-written, directed, and starring Orson Welles was released in 1941 and has long been considered one of—if not—the greatest films ever made.

Storyboarding a film in the early 1940s was still a relatively recent addition to the movie-making process in the very young film industry. Many historians agree that Gone with the Wind, which came out in 1939, just two years earlier, was the first live-action film to be storyboarded.

Unfortunately, we don’t have 150 hours of behind-the-scenes footage from the making of Citizen Kane like we do for The Beatles, but we do have these beautifully charcoal-rendered frames to give us a glimpse into the creation of what many consider a cinematic masterpiece.

Dreaming Big

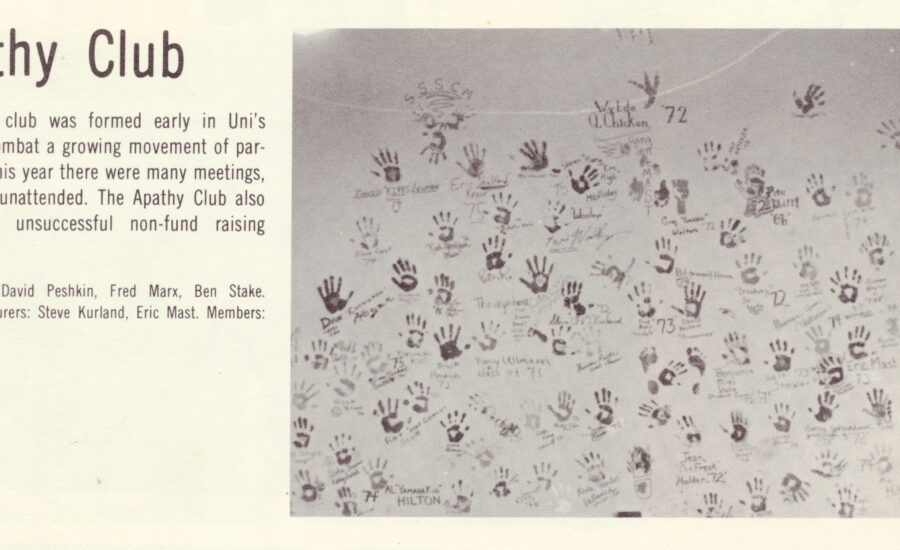

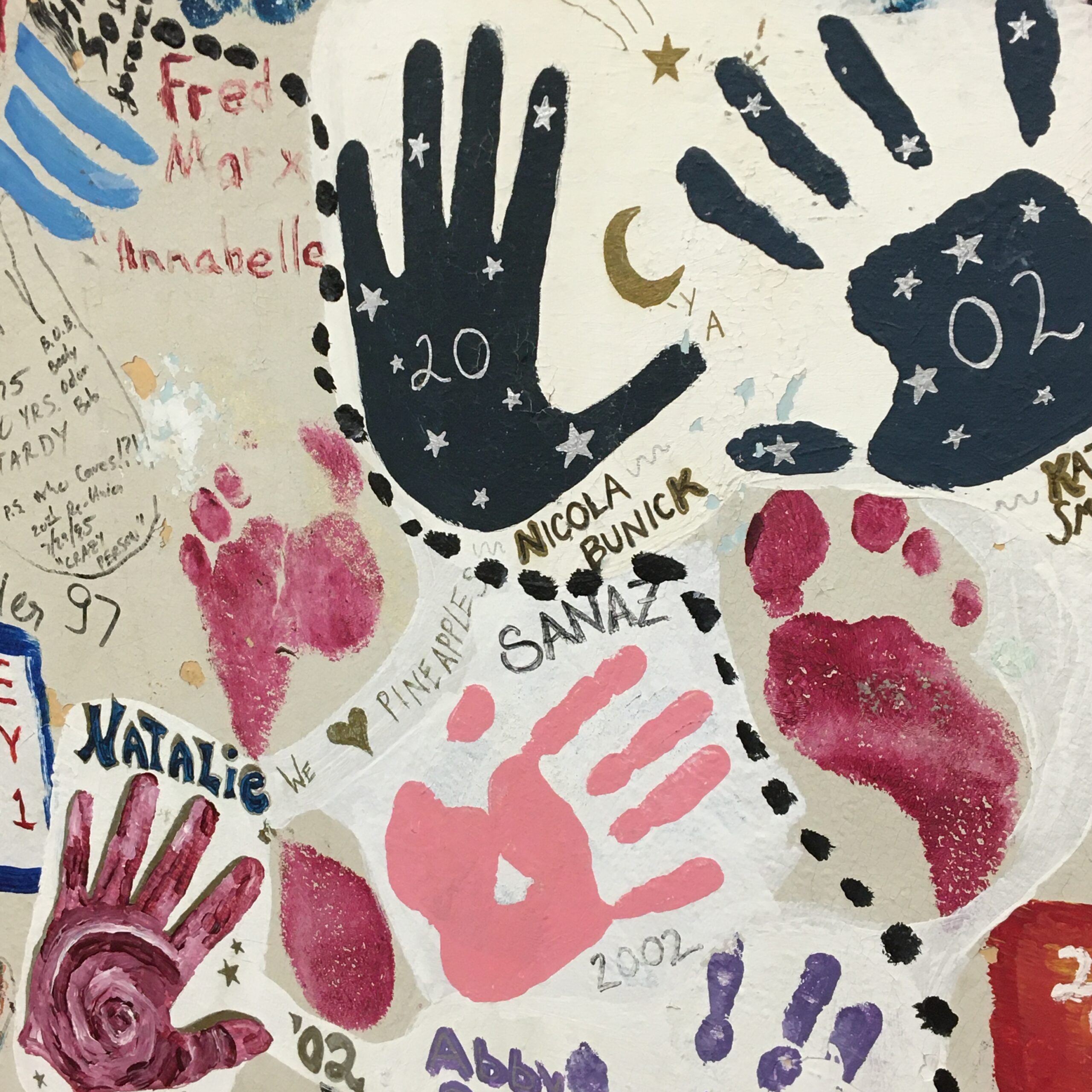

Perhaps inspired by the prehistoric cave paintings in Cuevas de las Manos in Argentina, University Laboratory High School students began adorning their own “cave,” also known as the student lounge, with handprints fifty years ago.

I floated that idea by Frederick Marx (UNI ’73, LAS ’77), but he recalled the project’s genesis very differently.

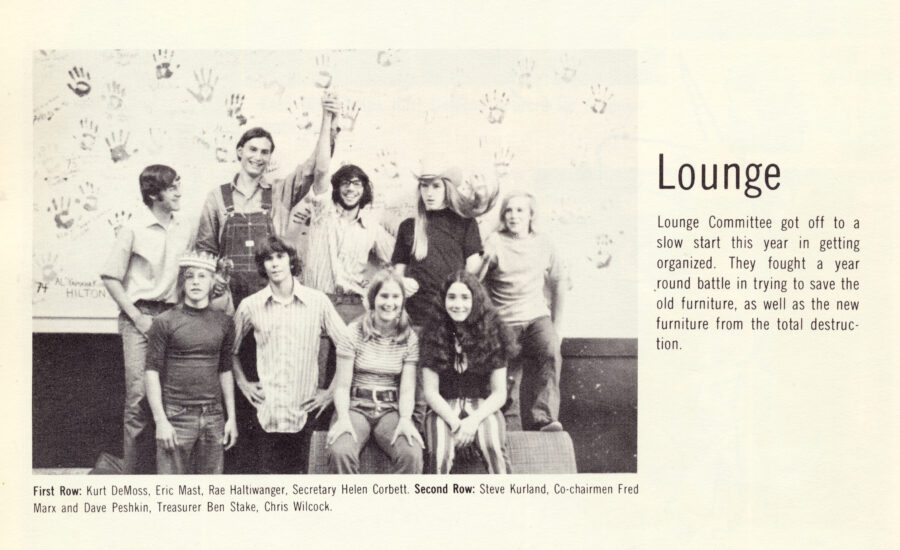

“I was on the ‘lounge committee’ in 1972—yes, I had, at the tender age of 16, already achieved my life’s greatest aspiration of being on a lounge committee—when we decided on this plan,” Marx wrote when I reached out to him recently.

“I could easily be wrong, but I think the idea of doing these wall prints was mine. Everyone did hands, but I wanted to do my feet [in red, above], because of the absurdity and ridiculousness of it.”

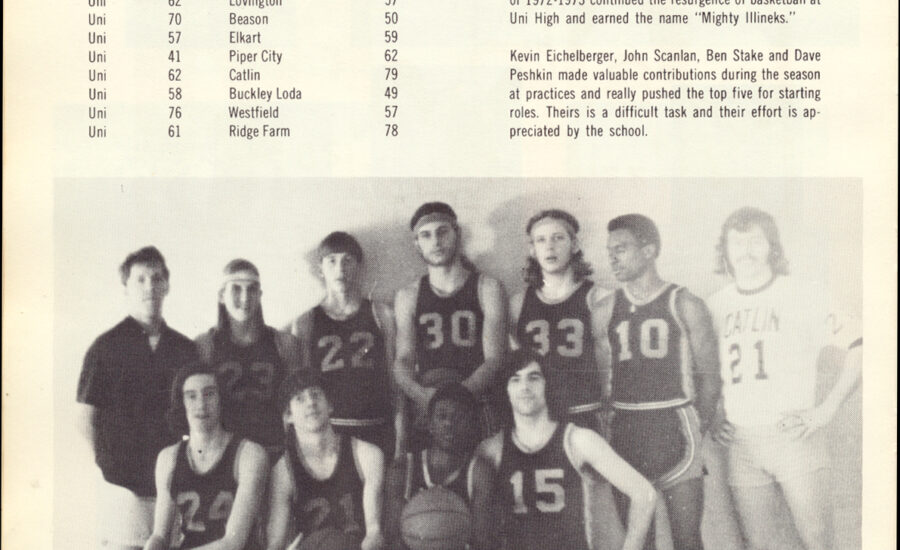

In addition to his lounge committee obligations, he was co-president of the Apathy Club and went by the chosen nickname Annabelle. Standing six foot five inches, he was a star player on the basketball team.

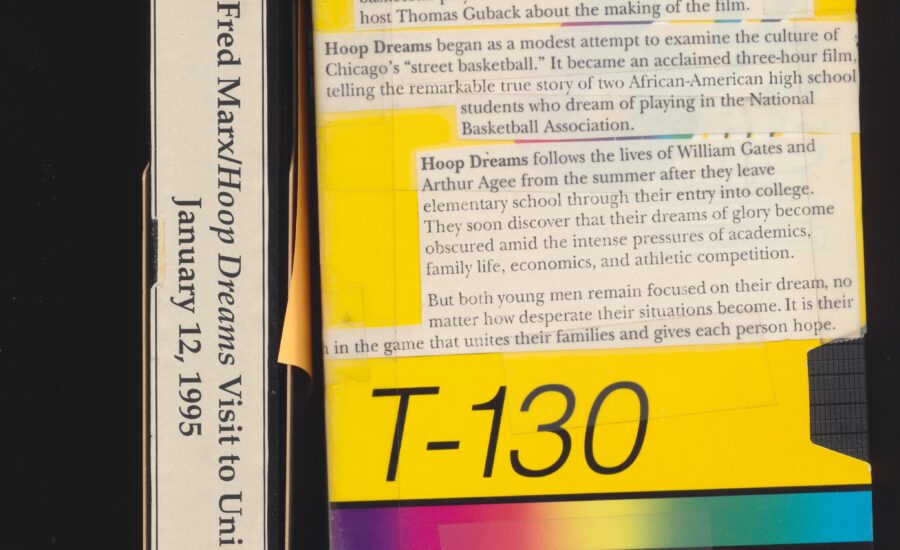

In all seriousness, it was his basketball days that led him to become one of the creators of the sports documentary game-changer Hoop Dreams.

The Oscar-nominated 1994 documentary centered on two Black Chicago high school students hoping to make it to the NBA while navigating complicated home lives. In his review, family friend Roger Ebert wrote, “A film like Hoop Dreams is what the movies are for. It takes us, shakes us, and make us think in new ways about the world around us. It gives us the impression of having touched life itself.”

Marx never stopped creating. The Emmy- and Oscar-nominated producer, writer, and director went on to create dozens of films and author two books.

Scripting a galaxy far, far, away

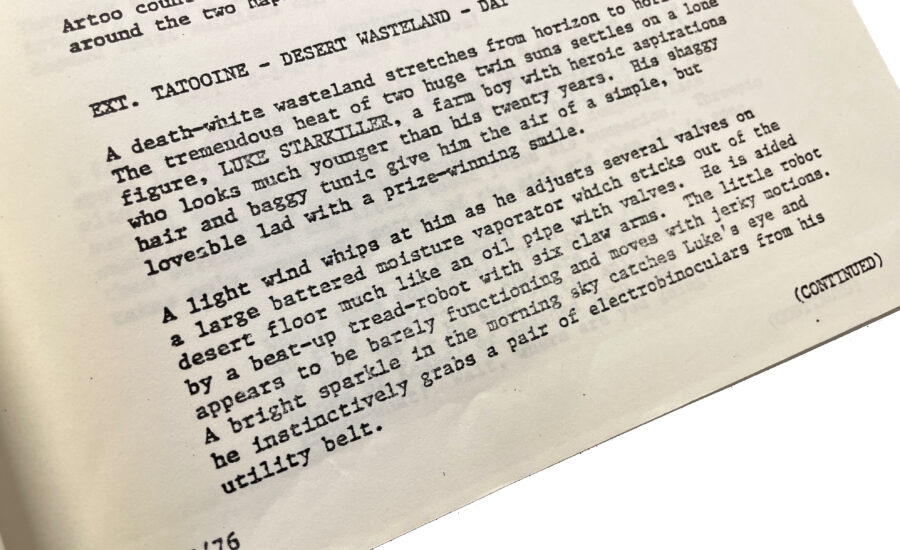

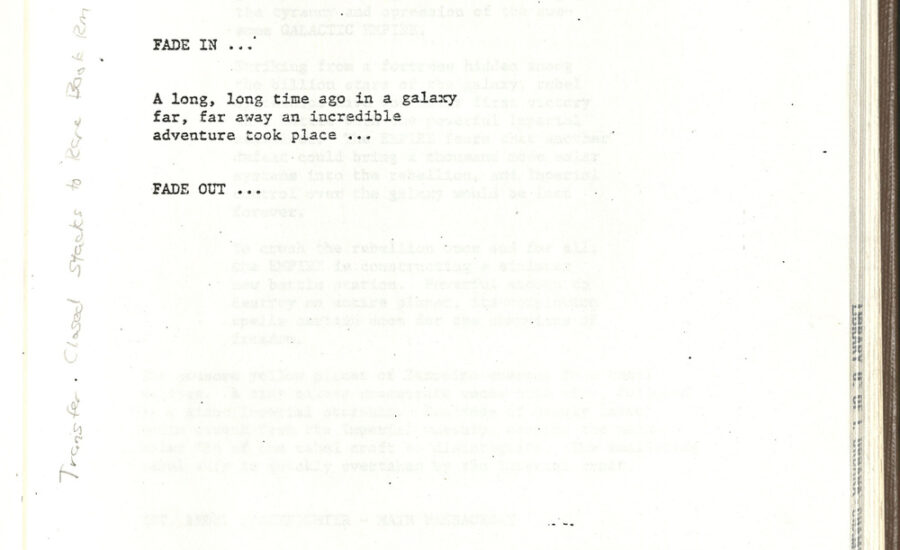

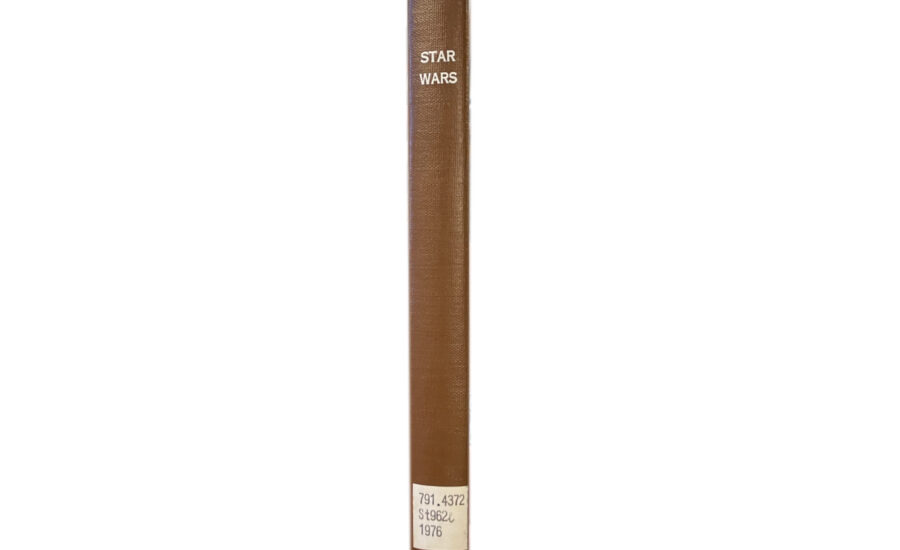

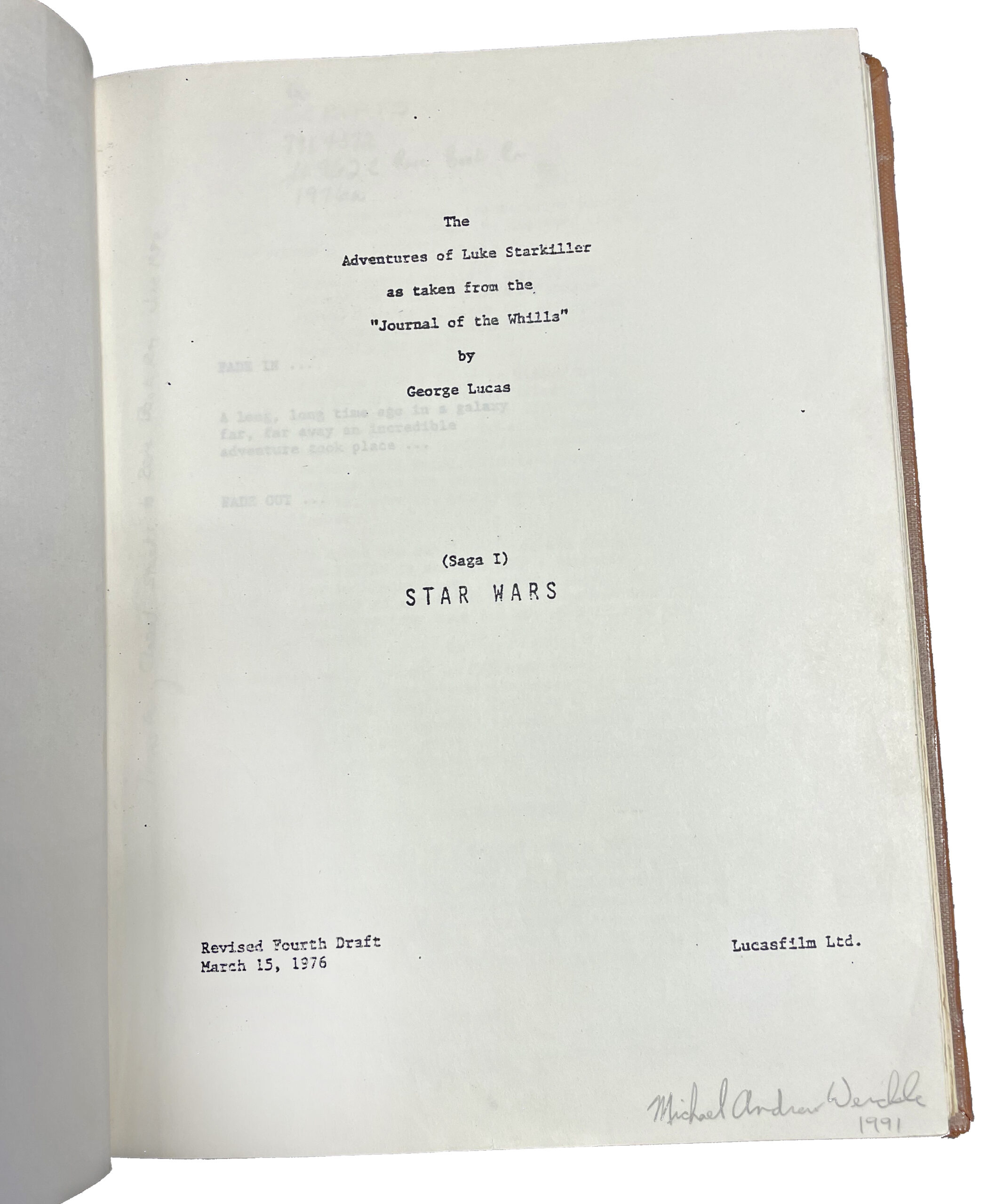

Remember when you first saw The Adventures of Starkiller taken from “The Journal of the Whills”? Doesn’t ring a bell? That’s because by 1977, when George Lucas released the film, it became better known as Star Wars. You can find a revised fourth daft of the script form March 15, 1976 at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML). You can also see Cait Coker, RBML associate professor and curator, page through the script in this From the Vault presentation.

The script is a photocopy bound in the library’s standard issue brown hardcover to protect the pages from deteriorating. All of the familiar characters occupy the pages like we remember, with the exception of one Luke Starkiller, who didn’t become Luke Skywalker until a few months into filming. According to George Lucas in the book, The Making of Star Wars, the use of Starkiller so soon after the Charles Manson murders wasn’t working. “I felt a lot of people were confusing him with someone like Charles Manson,” Lucas said. “It had very unpleasant connotations.”

Mark Hamill, who has played the part for 45 years, remembered his brief stint as Starkiller in this tweet.

Luke Starkiller.My name in Tunisia & London, months into prod. Filmed the “I’m LS here 2 rescue U!” scene w/ it. sad https://t.co/XPYaWjtbRG

— Mark Hamill (@HamillHimself) October 26, 2015