On the day we meet Dan Fisher, he pulls up in a cherry red, all-electric Ford Mustang. A bold color and a bold choice in Gillespie, a former coal-mining town about forty-five minutes south of Springfield.

His friends aren’t shy about giving him a good-natured hard time about his purchase.

“You need some gas for that car,” one insists. Dan’s used to it.

His large solar array electrifies his house that sits just a hundred yards from a reclaimed coal mine where healthy grass covers a problematic past.

The paradox is evident to him and everybody else in this small town of a little over three thousand—a town that keeps getting smaller.

Many of those who still live in Gillespie remember when the coal mines were the main engine of the local economy. But as the years have gone by, the importance of the industry’s impact on the community grows fainter. There used to be thousands of coal jobs in Gillespie and the surrounding towns in Macoupin County, but now that number has dwindled to less than a couple hundred.

Despite the closing of so many mines, coal is still part of the town’s identity. They celebrate Annual Black Diamond Days, a yearly festival that includes a carnival, parades, and a mine rescue demonstration. On Friday nights, the town cheers on the Gillespie High School Miners, the local football team. A profile silhouette of a miner with a pick hoisted over one shoulder hangs above the entrance of the school. The Illinois Coal Museum on Historic Route 66 displays artifacts from a bygone era.

These reminders of what Gillespie once was are still around. But the mines and the miners are not.

Yet, Gillespie is hardly alone. Coal communities throughout the state are grappling with a shrinking industry, and University of Illinois Extension is working with these areas to help them plan, imagine, even embrace a post-coal future.

Mining’s Mystique

Coal was discovered in Illinois in 1810, but was not mined in earnest until the 1850s. By 1870, as coal companies set up operations throughout the state, towns were established to support them. Place names throughout Illinois like Coal City, Carbondale, Diamond, Carbon Hill, Carbon Cliff, Glen Carbon, are obvious nods to the town’s original purpose. Others like Freeman Spur and South Wilmington were named after the coal companies’ owners.

To date, coal has been mined in 76 of the 102 counties in Illinois, and more than 7,400 coal mines have operated since commercial mining began. Even today, Illinois still has the largest reserve of recoverable bituminous thermal coal (used in power plants) east of the Mississippi.

Dan’s background is not unlike many other long-timers in Gillespie. His grandfather emigrated from Scotland in the early 1900s and brought with him his wife and their daughter. He chose Gillespie for the same reason many others from throughout Europe did—to work in the coal mines.

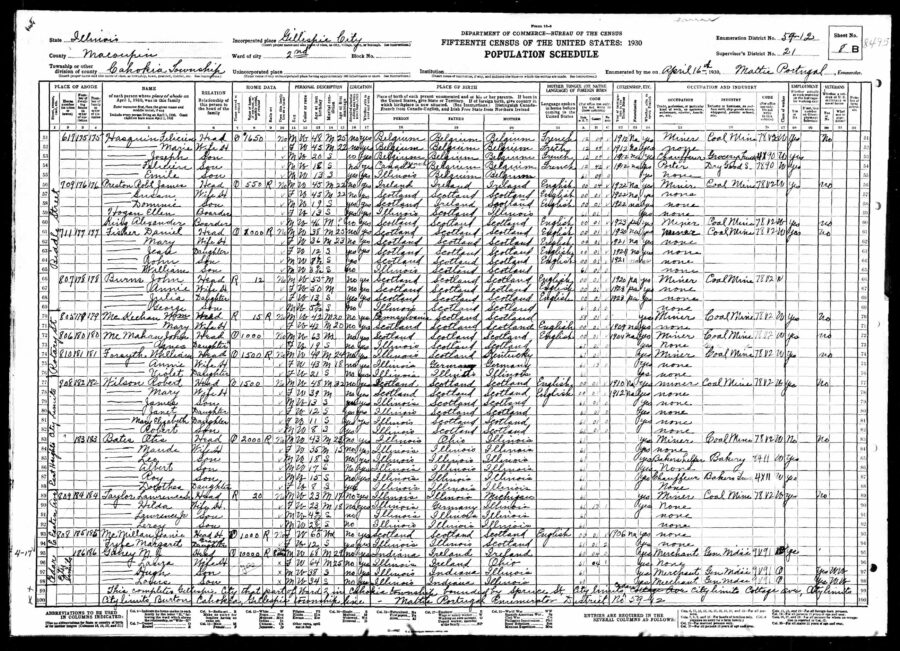

On the page of the 1930 census that listed Dan’s grandfather, eleven of the eighteen heads of households were miners. His next-door neighbors on Biddle Street and their sons worked in the mines too. Families like his left behind their homelands for a chance at a better life, even if that meant long hours, in the dusty, combustible, damp underground mines in the Illinois coal fields.

Dan’s father, William who was born in Gillespie, went on to be a miner as did the father of the woman Dan would marry.

None of the men lived to see seventy. As the saying goes, Dan shared, “If the big rocks don’t kill you, the little ones will.”

While Dan was born into a coal mining legacy, he chose not to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. The closest he ever came was as a kid in the 1950s playing on abandoned coal mines or climbing up mountains of hard-packed, rocky slag. He likened scaling the dusty elevation to being on the moon.

When we met Dan, who attended Illinois in the early 1970s, he offered to drive us around the greater-Gillespie area. He had something to say about every stretch of land, sounding like the mayor he once was from 2000 to 2004.

He slowed down and stopped in front of a big, empty field of grass in Benld, a neighboring town.

“All of this is built on mines,” Dan said with a sweeping gesture. “All these homes are on mine shafts, and this, right ahead of us, is where a multi-million-dollar elementary school once stood. It sank because of mine subsidence and we had to tear it down.”

A vast labyrinth of underground mines winds its way under most homes and businesses in Gillespie and Benld. Mining companies often hastily closed decades ago, leaving poorly reinforced mines. Today, residents are dealing with sinking structures. Subsidence insurance is a must for folks that own properties.

Because most of the mines in Gillespie closed by the late 1960s, the town got an earlier start in transitioning away from coal than other towns in Illinois. Today, Macoupin County has only one operational mine. That said, coal remains a part of the region’s identity.

“I think there is a cultural attachment to mining among the people that are in that industry,” Dan said. “It becomes part of their identity kind of like farmers and farming. Coal mining has a mystique about it.”

When Coal was King

The relationship between miner and coal company was reciprocal, but it was hardly equal. Company towns were just that—miners and their families worked, lived, and shopped by the coal company’s rules. At times, money was issued in the form of scripts that could be used in stores owned by the coal companies.

As the Industrial Revolution gathered steam in the U.S. in the 1880s, exploitation of coal’s workforce was rampant. It was not uncommon for strikes to be organized by miners demanding better working conditions and wages.

In 1932, dissatisfied with how negotiations were handled by John L. Lewis, the president of the United Mine Workers (UMW), 274 miners’ delegates met in the Colonial Theater in Gillespie and formally broke from the UMW to form the Progressive Miners America union (PMW). By 1933, the union had more than ten thousand members, and overnight, Gillespie, this small town on Route 66, became a big player in the organized labor movement.

These were the times when coal was king. The use of coal was crucially important to the rapid growth of industry, which fueled the country’s rise as a global power. It also served as the economic backbone of many small towns.

However, as the U.S. moved away from coal to gas in the 1950s, coal became an increasingly smaller fraction of what generates Illinois’ energy—from 52 percent in 1990 to just shy of 20 percent today. This is in large part because natural gas is cheaper, nuclear power came online, and renewables, like solar and wind, are becoming more reliable and more efficient. In addition, as a result of technological advances, coal companies now employ only a fraction of the people it once needed to mine.

Today, what’s true for just one Illinois community that supplies, burns, and ships coal is also the case for many, if not all of them: an enduring reliance on a coal-based economy is not only shortsighted but no longer possible.

Shaping Policy

Illinois just passed the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act that plans to eliminate the use of fossil fuels, a.k.a. natural gas and coal, by 2050. It also includes funding for communities to provide training for workers displaced by these changes. Although, curiously, it does not contain provisions for coal mining, and according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Illinois exports about 80 percent of its coal.

Kathie Brown, a University of Illinois Extension community and economic development specialist, has spent her career working with communities to inform state policy. She remembers when she first stepped into her role in Fulton County in 1980 and saw the vast areas of degraded, barren land strip-mining companies had left behind. She began her job soon after the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, which required mining companies to restore the land to its previous state once they were done.

She, along with other Extension specialists in coal communities throughout the state, have facilitated conversations among community members and policy makers about the effects coal plants and mining closures have had.

The meetings are meant to strategize and prioritize steps to take when a local economy is so profoundly disrupted by continued and sometimes sudden lost jobs and tax revenue. Kathie likens it to “bringing the pain points forward from a community perspective.”

“Those conversations help to shape local thinking around how to respond to these coal plant closures and how to grapple with what was happening in their local community. We were asked to share those conversations with the governor’s office,” Kathie said. “It was great to observe how these facilitated discussions as well as the documentation around what’s happening in these communities, really help to shape policy.”

Dan has been working with Anne Silvis, an assistant dean in Extension for more than thirty years. In 1989, when he was the coordinator for economic development for Macoupin county, Anne was his county’s liaison for an economic development pilot study that Macoupin, along with six other counties, was invited to participate in. Over the years, they have kept in touch and more recently, Dan reached out to ask for help with new project to redesign Gillespie’s downtown.

Extension specialists, Layne Knoche (FAA ’18) and Zach Kennedy (LAS ’07, FAA ’09), who work with Anne, are collaborating with Dan’s Grow Gillespie team to put together a plan to revitalize business downtown. Plans include attracting business to occupy empty storefronts, retain existing businesses, and beautify the business district.

“When we work with small communities, we ask them what their goals are, what’s their vision, and how are they planning to get there,” Anne said. “They’re always working on that. They don’t need any kind of a crisis—there is always a crisis.”

Other projects aim to increase tourism in the area. The Mythic Mississippi Project, supported by a University of Illinois Presidential Initiative for the Celebrations of the Humanities and Arts grant, has been working in the coal towns of Macoupin County in what is being called “the coal triangle route.” The project donated two historical markers, one honoring the PMA and another at the Miners Cemetery in Mt. Olive, the town next to Gillespie. Anthropology Professor Helaine Silverman believes these deep ties to coal mining could be a focal point of heritage and historical tourism that could also give economic and social boosts to the area.

Visiting Mother Jones

On that scorching day in August, Dan agreed to show us around the Union Miners Cemetery.

The three-acre cemetery was established in 1899 shortly after the Battle of Virden on October 12, 1898 when eight miners were killed during a strike that turned violent. Local cemeteries refused to take the bodies for fear of retaliation from the coal companies whose influence was so strong at the time. This parcel of land became the only safe resting place for the miners. A white outline of a miner wearing a headlamp adorns the entrance gate.

“That just shows you the clout the mining companies had over this area,” Dan says. “They were like gods.”

The main path leads to a monument of the cemetery’s most famous occupant, Mary Harris, better known as Mother Jones, who died in 1930. One of the most celebrated labor organizers in the United States, Jones requested to be buried alongside her “boys,” as she called the miners.

Even now, at the foot of her grave, union and political pins, inscribed rocks, shells, and a couple of pieces of coal sit in a pile like offerings to the “patron saint of the miners.”

“What Mother Jones and those miners fought for is what we still see to this day,” Dan says. “We have to provide an economy that provides for everyone.”