All around the world, people gathered to watch or to listen. A huge screen was erected in Central Park to broadcast the event. Soldiers in Vietnam huddled around transistor radios. People watched on televisions through store display windows, in bars and living rooms and conference rooms.

With collective anticipation, they listened to the staticky din of the communication between the Apollo 11 astronauts and Mission Control; they watched the first grainy images of the moon’s surface appear before them.

Of course, there was one room in particular where the men and women gathered watched more intently as the Apollo 11 astronauts carefully landed the lunar module on the moon’s surface.

Mission Control.

After astronaut Neil Armstrong’s legendary announcement that the Eagle had landed, Houston immediately replied: “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again.”

Indeed, the entire world began to breathe again.

John C. Houbolt (GRAINGER ’40 ’42), was in Mission Control that day, seated among the mid-century industrial consoles. Ashtrays and coffee cups were scattered on the desktops, awash with the soft blue glow of the computer screens.

“When the landing took place and the touchdown was made, all of us stood up and started clapping,” Houbolt said in a NASA story. “But at the same time, we were shh, shh, because we didn’t want to miss a fraction of a second of history being made.”

There were thousands of men and women who made this day possible, but Houbolt’s inventive vision and his fierce tenacity played a critical role.

THE RACE BEGINS

The mission to land a man on the moon began in earnest in 1961 after Alan Shepard became the first American to travel into space.

Millions of Americans held their breath as they watched Shepard’s journey. Upon his return, he was greeted as a hero with crowded ticker-tape parades.

The public was sold on space, and the Kennedy administration knew the time was right to announce grand plans. The Soviets had beaten the U.S. to space by only a few weeks, and the Americans were determined not to let them get to the moon first, too.

Only twenty days after Shepard’s mission and after an intense back-and-forth with NASA officials, President Kennedy stood before a special joint session of Congress and announced that an American man would land on the moon, and return safely, within the decade.

Kennedy said, “No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind or more important to the long-range exploration of space … In a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon. We make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation.”

With the deadline set, NASA set off to answer the ultimate question: how was this going to work?

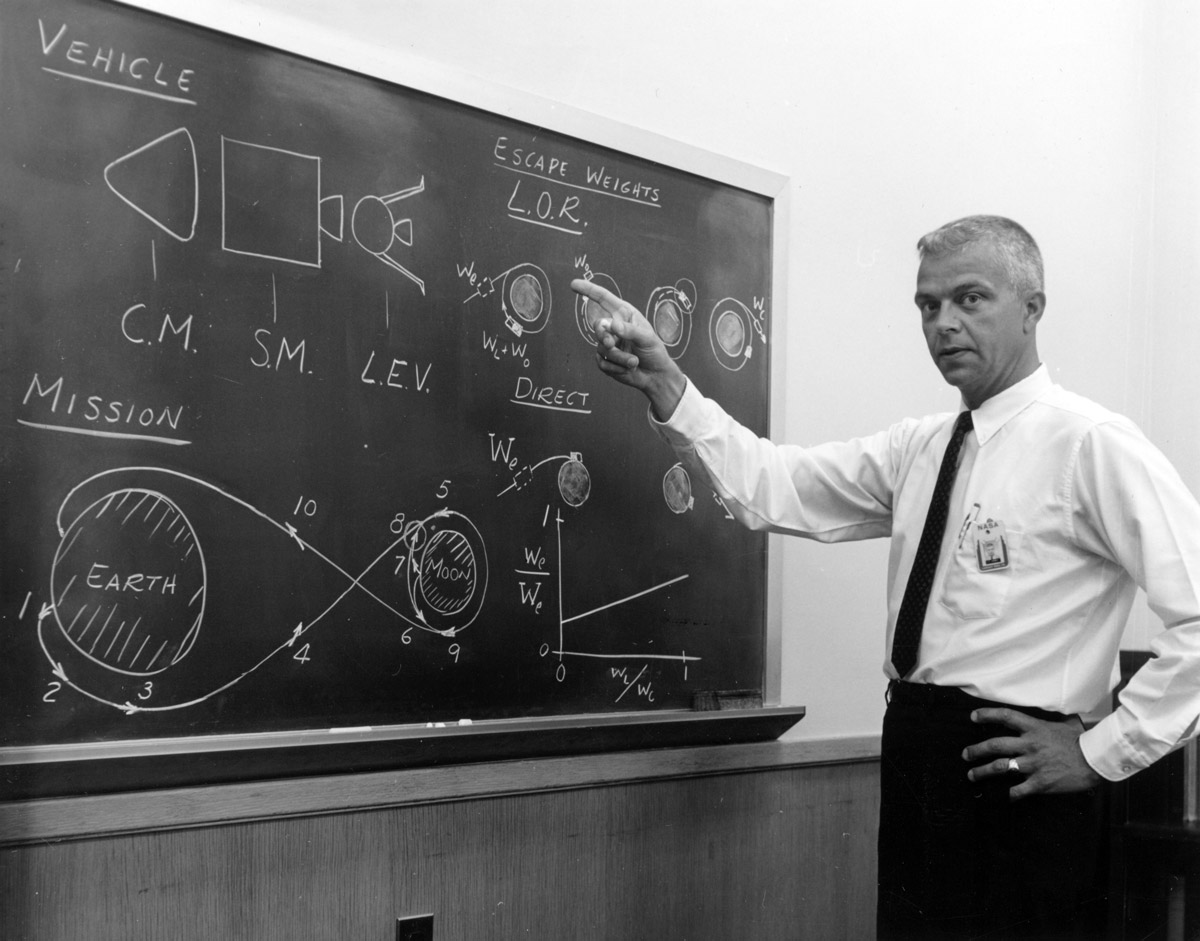

There were three methods on the table for landing on the moon.

The early favorite was the direct ascent method. Initially favored by Marshall Space Flight Center director Wernher von Braun, it appeared straightforward at first glance. NASA would use one rocket, land three men on the moon, and come back in the same vehicle. However, this rocket would need to be mind-bogglingly massive (a proposed rocket needed to be 430 feet tall and weigh 10,516,620 pounds), use an incredible amount of fuel, and be enormously expensive to build.

A second proposed method was Earth-Orbit Rendezvous, or EOR. This plan involved launching two smaller rockets — one carrying the spacecraft, and one holding fuel. They would rendezvous in earth’s orbit, the spacecraft would fuel up, and then head to the moon. The smaller rockets would make this option much cheaper, but a rendezvous in space had never been done and would be incredibly difficult.

This made the third method even more of a long shot.

Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous, or LOR, would use one craft. After launching into the moon’s orbit, a lunar module would break off and go down to the moon’s surface. Once the astronauts were done on the moon, they would use the module to launch back up, rendezvous with the main craft, and go back to Earth.

Most people thought it was ludicrous — and in a lot of ways it was.

The astronauts in the lunar module would need to rendezvous with the main craft using pinpoint accuracy at breakneck speeds. And in the moon’s orbit, there was no room for error. If something went wrong, the astronauts would have no chance of survival.

This plan had one particularly loud advocate: Houbolt.

He argued that the LOR craft would be lighter and save fuel. The lander would be smaller and easier to maneuver than trying to land a large craft. Despite the substantial risks, to Houbolt it was the only way the U.S. would make it to space before Kennedy’s deadline.

Houbolt was a relative outsider in the space program. He was not on von Braun’s team and did not have seniority. Houbolt slipped his advocacy for LOR into presentations, wrote detailed reports, and brought his argument to committee after committee.

“The reaction to the idea of having astronauts perform a rendezvous maneuver 240,000 miles from the earth was generally negative,” Houbolt wrote in a 1969 issue of The New York Times. “In some cases, direct hostility was evoked; in others the individuals thought we had ‘gone off the deep end.’”

Houbolt’s frustration mounted, and he decided to write to Robert Seamans, first in May 1961 in November of the same year. Seamans was an associate administrator at NASA, and by skipping over much of the NASA hierarchy, Houbolt was risking his job.

“Somewhat as a voice in the wilderness, I would like to pass on a few thoughts on matters that have been of deep concern to me over recent months,” Houbolt began in his November letter.

The nine-page letter outlined Houbolt’s main arguments. He also used the letter as an opportunity to ask Seamans a frank question: “Do we want to get to the moon or not?”

Seamans himself described the letter as “blistering,” but it caught his attention. Houbolt’s bold, unorthodox gamble paid off. There was still significant resistance to the plan, but slowly people started to come around and pay attention.

A fascination with flight

Houbolt’s tenacity was fueled by his family. Born in Iowa in 1919, he moved with his family to Illinois when he was a child and grew up on a farm near Joliet. His family raised crops, but primarily ran a dairy farm. He was a normal farm kid who did his chores and learned about hard work.

He developed a fascination with flying during this time. The flame was sparked after his father let a man use a field as a runway for 50-cent plane tours. Houbolt built model airplanes and competed in flight contests as his interest in engineering grew.

He went on to graduate from Joliet Township High School and excelled at Joliet Junior College before attending the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and majoring in civil engineering. He earned his undergraduate degree in 1940. He stuck around for two years for his master’s degree and was a part-time research assistant under Professor Nathan Newmark.

Houbolt left Champaign-Urbana to start his professional career at the predecessor to NASA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), at the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory. After winning the 1956 Rockefeller Public Service Award, he earned his PhD from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich.

After completing his doctorate, Houbolt returned to NASA taking a position as assistant chief of the Dynamic Loads Division at Langley, becoming chief of the Theoretical Mechanics Division by 1963.

The man with humble beginnings was now among one of the most elite scientists in America.

PREPARING FOR LAUNCH

By the summer of 1962, a little over a year from the time President Kennedy addressed Congress, Houbolt’s advocacy was finally successful. NASA announced that LOR was the method by which Americans would get to the moon. The approach did indeed create efficiencies that significantly reduced the time and cost involved in building the spacecraft. Ed Garrick, Houbolt’s boss at NASA, is quoted as saying, “I can safely say I’m shaking hands with the man who single-handedly saved the government $20 billion.”

Now that a decision had been made, the hard work of actually making it happen would begin. The scientists needed to work fast.

Kennedy’s decade deadline was looming, and the world was watching. It felt like do or die to make this work. In many ways, this was more of a political mission than a scientific one.

The Gemini missions in 1965 and 1966 allowed NASA to test multiple aspects of the Apollo missions, like rendezvous, spacewalking, and the effects of long-term spaceflight on the health of the astronauts.

“By the time we flew on Gemini, they knew your eyeballs weren’t going to change, they knew you could drink, they knew you could sleep,” astronaut Dave Scott said in a National Geographic documentary. “The fears were if you could perform after, say, a week in space up to the level you expected to. We really didn’t know, and we had to know in order to go to the moon.”

Tests were going well as a whole. Scientists were checking all the boxes they would need for a successful trip to the moon.

Those high on the triumphs of the Gemini program were quickly grounded after the subsequent Apollo program began with tragedy. During a pre-launch test for the first Apollo mission, three astronauts — Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee — died when the craft was engulfed in flames from an electrical fire.

This sent shock waves through the Apollo program and reinforced exactly what was at stake: the lives of astronauts, the faith of the American public, and the race against the Russians.

Luckily, the Apollo mission kept more or less on track after the tragedy, and ultimately, NASA made Kennedy’s deadline.

THE 20 BILLION-DOLLAR MAN

Although Houbolt was not with NASA at the time of the Apollo 11 mission, he was invited to watch the moon landing from Mission Control. He was not nervous per se, but he did feel a bit tense watching the lunar module make maneuvers it hadn’t practiced before.

“A funny thing,” he reflected in a 1969 interview with the Illinois Alumni magazine, “the rendezvous with the command module that followed the moon walk — the thing that caused people to be skeptical about our plan in the beginning — turned out to be exceedingly easy.”

Once derided for his vision and a thorn in the side of his superiors, Houbolt was now widely praised and recognized in the press by other members of the NASA team.

“I just thank my lucky stars that guys like Houbolt came along. I suppose that Columbus had some help, too,” said Caldwell Johnson, chief of the spacecraft design division at NASA in a 1969 issue of Time.

Anticipating the launch that summer, the March 1969 issue of Life described, “Eight years ago, the scheme seemed so bizarre that the obscure engineer who first suggested it was ridiculed. His lonely and courageous battle saved the U.S. billions of dollars, prevented years of delay, and if all goes well, will make a moon landing possible this summer.”

However, around the time the LOR decision was made, Houbolt left NASA. He had a wage dispute (he wrote directly to President Kennedy to try to solve it) and instead took an opportunity to work for the Aeronautical Research Associates of Princeton, where he was senior vice president and a senior consultant until 1975.

During those years, he stayed involved with NASA, and his LOR contributions kept making an impact — most notably during the Apollo 13 mission. The lunar module was essential in keeping the Apollo 13 astronauts alive when the service module on the spacecraft exploded two days into their flight. The lunar module served as a lifeboat of sorts and returned them back to Earth safely.

The University of Illinois Archives holds Houbolt’s papers and boxes of fan mail he received. Some came in after the success of Apollo 11, but even more flooded in after the world celebrated the Apollo 13 astronauts’ return. He received letters written by adults fascinated with space travel, as well as from elementary-aged children, who thanked him for his part in saving the astronauts.

He took the time to respond to many of them.

Houbolt eventually returned to NASA formally, and was the chief aeronautical scientist for Langley from 1976 until his 1985 retirement. He then continued in private consulting and eventually retired to Maine with his wife, Mary.

Houbolt died of Parkinson’s disease in 2014 at age 95, and had arranged for his family to donate his brain for research at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Despite the celebration around the lunar module successes, as time went on, Houbolt’s name faded somewhat into the background. We remember that small step and that giant leap, but not always the story of the dogged determination on the part of one man to make others see his vision. His impact on the space program by those closest to it, however, was not forgotten. In his NASA obituary, he was described as “Dr. John C. Houbolt, so little known, but a man of great ideas and bravery.”