On his computer at the Natural History Survey, Sam Heads scrolls through the postcard-worthy photos of the Ruby Valley nestled in the Rocky Mountains of southeastern Montana.

He pulls up a photo of a hillside peppered with small rocks and short, scrubby sagebrush. The truck bed of a bright red Ford pickup is wide open, full of tools and supplies.

“That’s Site 3, which we call the Kirkland site now,” Sam says.

He always wanted to dig at that site, ever since arriving in the United States from England in 2009. He came here to do an insect paleontology post-doc and is now a paleontologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey.

The land is on private property in what’s known as Fossil Basin, and boasts of a treasure of insect and plant fossils from between 34 and 23 million years ago, a time known as the Oligocene Epoch.

Sam felt that period of time, which can be described as a period of ecological transition between an earlier sub-tropical climate to the one closer to what we experience now, was essential to explore.

“It’s important not just because it neatly fills in a gap,” Sam explains, “but because it happened at such a dynamic stage in the climatic evolution of North America.”

It was also a site, that as far as he knew, had not been seriously explored since botanist Herman Becker published a book about it in the 1950s.

Finally, with a grant from the Prairie Research Institute, he got his chance in 2015 and again 2016.

✦ ✦ ✦

Paul Kirkland lives with his little dog in a sprawling ranch in Portland, Oregon. The house is packed from top to bottom with the treasures from a lifetime of fossil collecting.

Paul, who is 65, got his start doing preparatory work on fossils at the Los Angeles County Museum when he was in his 20s. He ended up moving to Oregon many years ago to be near his mother.

Twice each summer from 1992 to 1996, Paul traveled 800 miles to the same Ruby Valley site. Sometimes with a girlfriend or his son. Sometimes alone.

At the end of each trip, he would return with buckets full of rocks containing thousands of specimens.

He eventually tired of the long drives to Montana and turned his attention to preparing and curating the collection he already had. Just like Sam, Paul, too, thought he was the only person other than Becker to dig at that site. That is until 2016, during some routine web surfing when he stumbled upon Sam’s post on the Illinois website.

“I got in touch with him and told him that I had some really interesting material from there and had been collecting there for quite a while,” Paul recalls. “Sam was really surprised that anybody else had even collected there besides Dr. Becker.”

After several exchanges of photos and GPS coordinates, Paul and Sam knew they had been collecting in the same spot.

Paul also knew that Sam and the University of Illinois would be the best place for his collection.

“I want to make sure that all this stuff doesn’t end up in the dump or a rock shop if I die,” Paul remembers telling Sam. “I am happy to give it to the university. It will be there for posterity. I’ll actually have something to contribute to human knowledge.”

✦ ✦ ✦

It was impossible to mail the fossils, some of which are paper thin, so Sam grabbed colleague Jared Thomas and a mutual friend, rented a minivan, and headed out on the three-day, 1,500-mile trip from Urbana to Portland.

“It’s always exciting when you know there’s another collection that exists and to hear that Paul had this very large collection of several thousand specimens,” Sam says. “The immediate place your head goes to is ‘I wonder what’s in there? What might that collection contain?’”

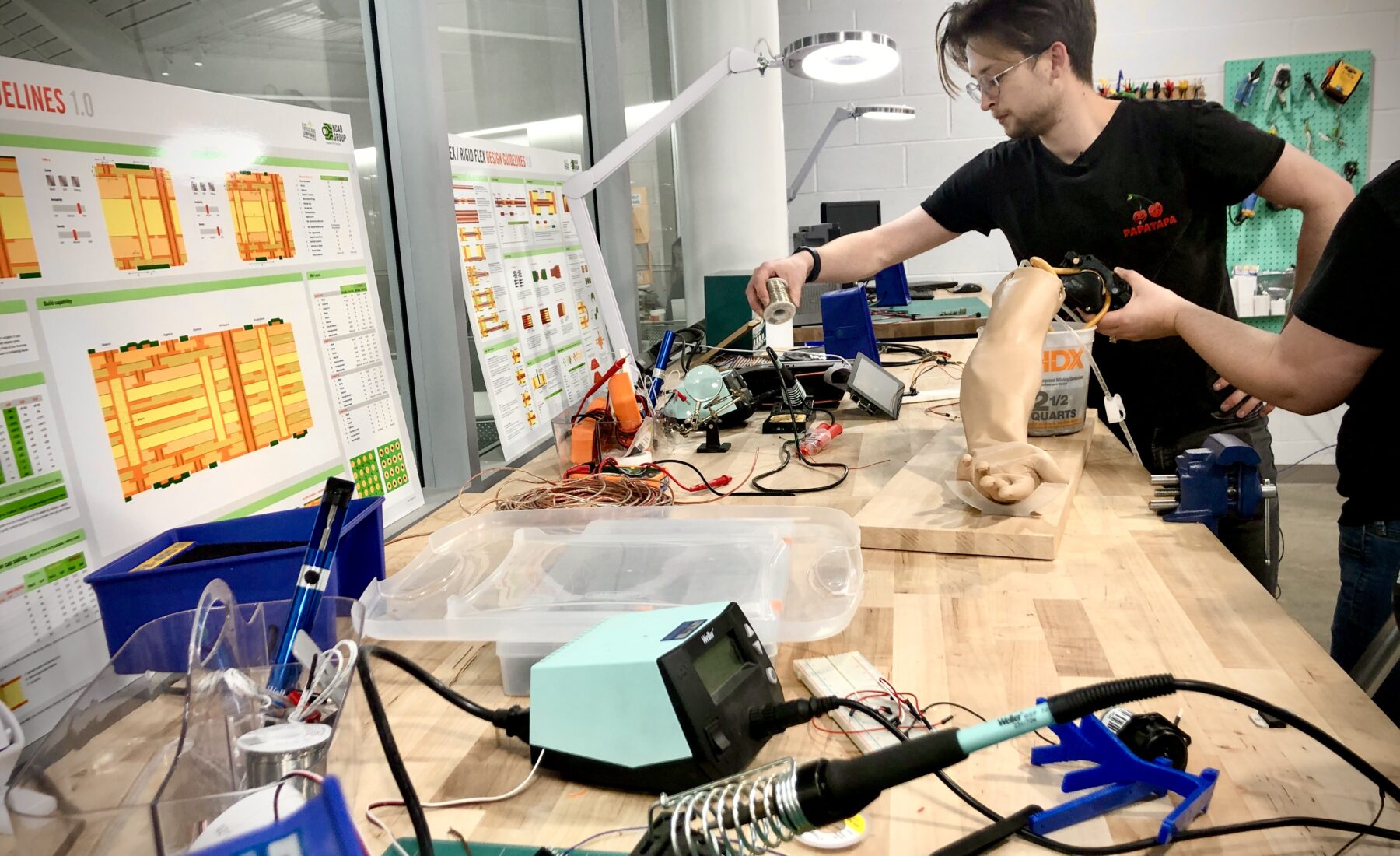

What Sam discovered was more than just a vast collection. He discovered a fellow paleontologist—a very skilled, albeit amateur one—who cared for and meticulously catalogued his fossils. Sam thought Paul’s fossil preparatory skills rivaled that of a professional.

“Paul knows where everything is, what it is, where it came from, and when he collected it. He has one of those memories,” Sam says. “He’s able to put everything he has into some geological context and some sort of spatial and temporal context. And that’s really valuable to make the material scientifically useful.”

All of that information made it much easier for Sam and his team to start going though the almost ten thousand pieces.

Although they’re far from cataloguing everything, they have already discovered a new species.

“We’re going to name a new longhorn beetle, a big one actually, that would be appropriate to name after Paul as a thank you for all the work he’s put into this collection and for donating it to us for research purposes—it is one of his favorite pieces,” Sam says.

This story was published .