We’re standing in a cramped cardiology room with Nana, a six-pound, long-haired Chihuahua from Thailand. There are at least a dozen people in this darkened room that smells like freshly-delivered pizza – a gift from U. of I. veterinary cardiologist Dr. Jordan Vitt to the two visiting doctors from Bangkok. Two other furry patients and their veterinary student caretakers wait their turn at the echocardiogram. Up next: a meowing tabby kitten with a heart murmur and a West Highland white terrier with sick sinus syndrome, an irregular heartbeat that reduces blood flow to the brain and causes it to periodically faint.

But Nana is on the table now, her brown eyes bulging as Vitt uses ultrasound to explore the contours of her heart. The Chihuahua licks her muzzle and squirms a little while Dr. Natpreeya Premjaroen, a veterinary cardiologist from Kasetsart University in Bangkok, wraps her arms around Nana and whispers softly to her in Thai.

But Nana is on the table now, her brown eyes bulging as Vitt uses ultrasound to explore the contours of her heart. The Chihuahua licks her muzzle and squirms a little while Dr. Natpreeya Premjaroen, a veterinary cardiologist from Kasetsart University in Bangkok, wraps her arms around Nana and whispers softly to her in Thai.

Nana’s heart is enlarged, the result of a flaw in her early development. A small blood vessel that allows the fetal circulation to operate properly in the womb failed to close at birth. This allows oxygen-poor and oxygen-rich blood to intermingle in the pulmonary artery, which normally carries only oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. This condition, called patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), occurs periodically in newborn dogs, humans, and other mammals – and is often life threatening.

Nana is special, however. She’s survived three years with this condition. Most dogs – and human infants – won’t make it that long with a PDA. But Nana’s heart has grown extremely large to make up for its inefficiency. It’s nearly twice its normal size.

Vitt talks a couple of veterinary students and the Thai doctors through what he sees on a monitor in the back of the room.

“Here’s the aorta, the aortic valve. Here’s the pulmonary artery,” he says. Nana wags her tail and licks her snout as the ultrasound probe pulses over her heart. On the monitor, the team can see the inner chambers of her heart, pumping madly. Flashes of blue, green, red, and yellow flood through an almost imperceptible opening. Vitt freeze-frames one shot.

“This is the ductus,” he says, pointing to a small dark gap between two flaps of tissue that make up the vessel walls. “And that’s the tiny hole, right there.”

He takes some measurements on the screen. The hole is 2.6 millimeters in diameter, the width of a fat pencil lead.

Vitt’s colleague Dr. Ryan Fries enters the room, happily swoops Nana up in his arms, and cradles her face to his. He is coming to look at the ultrasound. Tomorrow, the two doctors will repair Nana’s PDA.

✦ ✦ ✦

The cardiac unit at the U. of I. Small Animal Clinic is a busy place. A steady parade of four-legged patients, most from nearby communities in Illinois, comes here for diagnostic tests and procedures to correct or at least mitigate the problems found. On this day, the team is also seeing an Australian Cattle dog named Tumbleweed and a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel named Adelaide, each with their own special heart problems and needs.

Apart from Vitt and Fries, the cardiologists who direct and supervise the veterinary students, another person in the room plays key a role here. Saki Kadotani, a first-year cardiology resident, keeps track of vitals and assists the doctors. When she has a moment, she looks through a notebook to get a tally of the procedures conducted here.

“We’ve performed 30 to 40 procedures a year over the past three years,” she says.

In the last 12 months, the team has installed 13 pacemakers; completed 14 PDA repairs – not including Nana’s; and performed seven balloon valvuloplasties, a procedure that opens up blocked pulmonary valves with tiny inflatable balloons. The team performs a variety of other cardiac interventions as well, including heartworm retrievals. This involves grabbing the worms with tiny pincers fed through the jugular vein when too many of the parasites make their way into the chambers of the heart.

Now it is Nana’s turn. She will have her PDA repaired, a nonsurgical procedure that will permanently plug the hole between her aorta and pulmonary artery. In the process, she will become an ambassador of sorts. She’s here for a trial run of a new effort to broaden the College of Veterinary Medicine’s impact well beyond the borders of the state, to a part of the world that could use some help.

✦ ✦ ✦

Dr. Kanokporn Klivoraporn (whose nickname is “Gift”) and Dr. Premjaroen (also known as “Ohm”) are young veterinarians who spend much of their time in veterinary cardiology back home at Kasetsart University. They are not board certified in cardiology – such specialized training is currently not available in Thailand – but they work with veterinarians who have decades of experience working with a variety of cardiac patients.

Vitt met Klivoraporn and Premjaroen when he traveled to Bangkok earlier this year to teach a course at Kasetsart University. When he learned that the veterinarians in Thailand were unable to fix a PDA with the same procedure common in the U.S., he saw an opportunity to create an educational exchange.

On average, the hospital at Kasetsart treats 600 animal patients a day. Ohm estimates that her cardiology team sees about 20 animals per day, a much higher caseload than at Illinois. But the Thai veterinarians don’t have the equipment or expertise to perform some of the procedures available here, including noninvasive catheterization for PDA repairs. In their hospital, the only option for an animal with a PDA is open-chest surgical repair, a costly and risky procedure rarely performed in a country with a large population of needy cats, dogs, and other animals.

The interest in improving animal welfare in Thailand is acute – as is the need. Thousands of dogs and other animals live out their days in animal shelters in the bigger cities. In more rural areas, it’s not uncommon to see feral dogs and cats on the streets. Thailand is largely Buddhist, and so the idea of euthanasia is unpopular. This means more animals live longer with sometimes debilitating diseases. Being able to perform state-of-the-art procedures like PDA repairs or pacemaker implantations could make a huge difference for a lot of animals.

✦ ✦ ✦

Fries and Vitt are now in one of the Small Animal Clinic’s operating rooms. A team of students wheels in Nana, the now deeply anaesthetized dog. There are 10 people in this room, including Gift and Ohm. Each person wears a sterile gown and cap and a lead apron. The aprons block radiation from the fluoroscopy unit, which allows the team to watch their progress on a monitor as they thread a wire, a catheter, and an array of other devices into Nana’s femoral artery and toward her oversized heart.

A group of veterinary students stands in an observation room to one side of the OR.

“Dr. Vitt always wears that Little Mermaid hat in surgery,” one of the students tells me when I ask. “His mentors during his residency had it made for him.”

The students in the observation room can’t hear the banter in the OR, but they have a clear view of what’s going on. Vitt is careful to set up a monitor for them. The more experienced students narrate parts of the procedure.

Nana is moved to the OR table. Vitt covers her body with a sterile cover, and cuts a hole in the drape to expose a bit of flesh – her freshly shaved inner thigh. This is where the first catheter will be inserted into her tiny artery.

✦ ✦ ✦

Flying a dog here from Thailand is no small feat, and Nana had quite a team working together to get her to Central Illinois. Kasetsart University sponsored Klivoraporn’s and Premjaroen’s travel, excited for the opportunity to build a relationship with Illinois. While Nana’s owner paid for the dog’s travel and much of the cost of the procedure, Nana also had a surprise benefactor. A very grateful client whose own dog benefited from a PDA repair earlier this year at the U. of I. made a generous donation to the cardiology service. Part of that donation covered the remainder of Nana’s PDA repair and post-procedure care.

This short visit is allowing the Thai veterinarians to observe PDA repairs, pacemaker implantations, and a host of other procedures, including echocardiograms in animals of all sizes. They also are able to see how the U. of I. team incorporates its students, residents, consulting services, and client interactions into their daily practice.

Vitt, who visited Kasetsart earlier this year and sparked this collaboration, is also learning from the interaction.

“For example, the entire hospital in Bangkok is very understaffed,” Vitt said. “A lot of times, the pet owners are sitting in the room, giving medications and administering intravenous fluids to their own animals and monitoring them because there are not enough hands to keep up with the huge caseload.”

This may seem odd to Americans, who expect medical facilities to take charge of their patients. But it is done out of necessity and allows the Thai veterinarians to see more patients requiring their expertise, he said.

The Thailand animal hospital also has a more efficient way of handling diagnostics such as imaging studies, blood pressure assessment, or bloodwork, Vitt said. Technicians perform these diagnostics, allowing the doctors to have the information readily available when they first see the patients. At Illinois, things are set up so that the students can observe every step, from history and physical examination assessment to formulating diagnostic and treatment plans.

✦ ✦ ✦

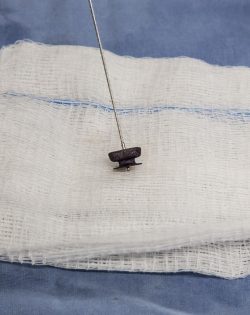

After an hour of painstaking work, the team is poised to fix Nana’s heart. Her tiny femoral artery, which runs from her inner thigh to her aorta, is now host to a series of catheters and wires. The team has already passed a catheter, which houses the device, across the defect in the dog’s heart. A tiny device called an Amplatz Canine Ductal Occluder (ACDO) is ready to be deployed, compressed inside the sheath.

Once the team has the tip of the occluder in exactly the right location, they will slowly retract the catheter while simultaneously pushing on the wire attached to the device, to carefully tease the rest of the ACDO out of its sheath. If all goes well, the occluder will spring into place, plugging the hole near Nana’s heart. For the first time in her life, the oxygenated blood of her aorta will flow efficiently to the rest of her body, permanently separated from the oxygen-poor blood that flows to her lungs.

“You’ll see the device moving with the heart beats and – hopefully – it won’t go anywhere,” Vitt told his students just before they went into the operating room. “Sometimes the PDA can dilate. You won’t be able to tell which patients are going to do that, which is the scary part.”

If the PDA enlarges, the occluder can dislodge from the vessel. The normal high blood pressure in the aorta could force the device back into the pulmonary arteries and toward the lungs. If everything goes wrong, the device could block an artery altogether, creating a pulmonary thrombosis – the equivalent of a blood clot in the lungs – and an emergency for the patient.

To avoid this outcome, the doctors are careful to size their devices precisely. When Nana was first brought into the OR, the team performed a second ultrasound – this time through her esophagus, to better visualize the PDA. And now, before proceeding, they inject a bit of contrast agent through the catheter into the PDA to clearly see the opening and take its measure one more time. All their imaging studies agree. The opening is 2.6 millimeters. Their ACDO is correctly sized with a 5-millimeter waist, nearly twice the size of the defect.

Vitt and Fries hover over their patient, gently threading the device into place just above Nana’s throbbing heart. After a few tense moments, the occluder is in place. They inject more contrast agent to check the positioning of the device. Then they wait, to see if it holds.

✦ ✦ ✦

Six weeks after her procedure, Nana has been home for a month. Her owner takes her for a walk in the park. He is delighted with her rebound after the procedure, and Nana seems delighted, too. She seems more playful. She gets less winded after racing uphill or climbing the stairs. Her appetite has improved. She seems more relaxed.

But the benefits of Nana’s visit to Illinois go far beyond this one dog’s improving health. By making this epic journey, this little Chihuahua connected veterinarians and animal lovers on opposite sides of the planet. She opened a door through which cultural and academic exchanges will continue, for the betterment of countless other animals – and their doctors – here and there.

This story was published .