The first call came when he was in a meeting at the Pentagon. At the time, Mike was special assistant to the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. When he returned to his desk after the meeting, a voice mail was waiting for him from NASA. He returned the call in the Pentagon’s courtyard, a lush five acres filled with trees and sidewalks cutting through green grass, not unlike the Quad. Mike paced back and forth while the phone rang, anxious until he heard then Chief Astronaut Steven Lindsey’s voice. “Mike, how’d you like to come work in Houston?”

Mike began dreaming about being an astronaut as a teenager in rural Missouri. Even after everything Mike did to prepare for that moment—his aerospace engineering degrees from Illinois and Stanford, his service in the Air Force—he couldn’t be sure he’d end up at NASA. Choosing astronauts is a very selective process. “Everything you do is building up toward that moment, and yet you don’t know if it will work out in the end. So there was no indication along the way that yeah, I’m doing the right thing. In fact, I have three rejection letters from NASA prior to being selected,” he said. “I think that’s where the perseverance comes in, the determination. I was just going to keep applying until NASA said, Mike, you don’t need to bother applying anymore.”

Mike didn’t realize he would receive a second momentous call just two short years later. That second call came as a summons to the office of the Chief of Astronauts. After an intense basic astronaut training program that included hundreds of hours of classroom work, simulator runs, practice spacewalks, and T-38 flights, Chief Astronaut Peggy Whitson sat Mike down and assigned him to a mission. “The emotions in that moment,” he paused to find the words. “It became more real. When you are in training, you get to practice being an astronaut—but you are still down here on Earth. It wasn’t until she said they were assigning me to a mission, that it really sunk in. I was going to space!”

When the rockets finally fired on the launchpad at Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in September 2013, Mike breathed a sigh of relief. “Up until that point, you are always worried about getting sick, getting injured, or just for whatever reason, they need to move somebody else into that slot. So the moment that rocket lights, you finally know, ok, I’m going to space. It’s really happening,” he said. He allowed himself that brief moment of relief before the muscle memory kicked in, and he focused on his duties in the spacecraft. Mike was on his way.

For most of us, traveling to space is the stuff of movies or books. Our imaginations are rife with what we think it might be like. Mike is one of the fortunate few who have viewed our planet from that vantage point, taking in millions of acres of desert, then mountains, then ocean in a whirl of extreme speed (17,500 miles per hour to be exact). Living in space is not an experience easily forgotten, nor one that leaves a person unchanged. Mike shared his experience with STORIED, hoping to reveal even a small notion of what it is like to see the sun rise and set sixteen times a day.

On shifting perspective

When I got my first good view of the earth, it was from the Cupola, this very large window at the bottom of the station that looks down on the planet. How do you even put that in words? It was one of the most surreal moments in my life.

There is something so powerful about seeing the earth in its totality. To pull yourself off the ground and be not just one human with the ability to see and feel the space immediately surrounding you, but instead to shift your perspective so drastically. From 250 miles up, the mountains look alive, almost like they are growing because you can see the valleys and the peaks and the snow and the shadows. The deserts are painted in these amazing geometric formations that are made by the wind. I don’t mean for it to sound simple when I say I’ve gained a greater appreciation for everywhere and everything. There is something special about this planet.

Most importantly, that appreciation extends to my family, my relationships, and the great people that surround me. When you fly into space, it is unbelievable how many people on the ground it takes to make that happen. When I landed after 166 days in space, one of the things that I wanted to refocus on was my family, to spend more time with my kids and my wife. I’ve had this career in the military that has been absolutely amazing, but there’s been a lot of time away and a lot of time where I was very focused on the job. I felt like when I got back I wanted to find a better balance, and I’ve been able to achieve that.

One more promise I kept? When you are on station, you don’t experience weather. No wind, no change in temperature, no rain, no snow. But when you get back on Earth, you realize it’s all part of being alive and living on Earth. When I got back I told myself I was never going to complain about the weather ever again. I’ve stuck to that so far!

On heartbeats and anticipation

On heartbeats and anticipation

When you are living in an environment like the International Space Station (ISS), there is this cacophony of noise around you at all times. Life support equipment, water recycling equipment, the sound from experiments or exercise machines—you name it. It doesn’t dominate the space, but it becomes something you are constantly aware of. To me, it sounded like a heartbeat.

One of my favorite times on station would be at night before we would go to bed. The last person would shut down all the lights and everyone else would be in the crew quarters. There would be this very quiet, very peaceful moment. A soft light remained from the little lights on the computers and other equipment. It was in those moments at night, all by yourself, that the sounds, the heartbeat, were really noticeable. To me, that sound symbolized this special relationship between the astronauts and the ISS itself. The hum of those machines was humbling. It reminded me of how dependent we were on them to keep us alive, and how they allowed us to do our work for NASA and the nation.

The sounds were similar, but more amplified, when I went outside ISS for two spacewalks. In my suit, I could feel the cool movement of air across my face, and hear the sounds of my backpack which held all of the life support equipment that kept me alive. If I was in the ISS and there was a problem with one of the modules, I could go to another module to be safe. But when I was outside on those spacewalks, there was nowhere to hide and that equipment was the only thing keeping me alive.

The emotions I experienced before my spacewalks reminded me quite a bit of my time at Illinois, when I would stand in the tunnel with my teammates at Memorial Stadium waiting to run onto the football field for a game. There’s this nervous energy, and again, a background of sounds that become tied to that moment. You can hear the other players anxiously moving around or jumping up and down, shoulder pads clacking and cleats scuffing the turf. Then there is the announcer going through his pre-game script, and the murmur of a gathering crowd talking and getting ready for the game. We’ve spent hours preparing and the wait is finally almost over. Spacewalks begin the same way—five or six hours of preparation that lead to a snapshot in time, looking out the airlock hatch much like the tunnel of the football stadium, with many of the same emotions—the nervousness, the excitement, the anticipation.

And behind these emotions are the background noises that become the soundtrack to a point of transition—from a safe environment where you wait in anticipation to the energy and focus of finally being in the moment. Now the game is happening and you get to do what you spent all this time training for and waiting for. From the tunnel, I’d look out at tens of thousands of people waiting to watch us play. From the airlock hatch, I got to see the earth going by with nothing but the vacuum of space between me and our beautiful planet. Incredible moments.

On grit

On grit

When I was young, I would spend hours working with my father on our farm in rural Missouri. We’d drive miles and miles of fence posts, and he’d always say to me, “All it takes is one more lick. You got one more lick to get that last post in the ground?” Any amount of grit, of perseverance, comes from my parents. I was encouraged to never give up on my dreams—but also to expect achieving them would be hard work. That seems natural to me. I took that with me from my very first Fighting Illini practice as a freshman walk-on staring down three defensive linemen, all the way through to becoming captain my senior year. It stayed with me from the moment I began dreaming about becoming an astronaut to when I heard and felt the rocket fire below me.

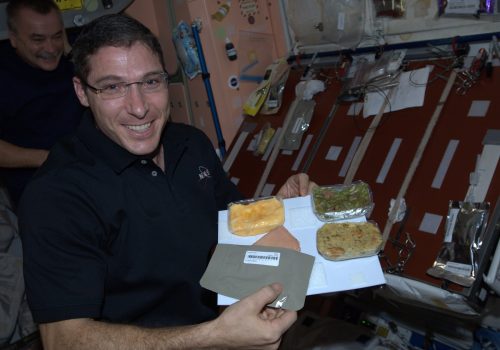

Astronauts are allowed to bring a few personal items with them to the International Space Station. One of the things I brought with me was my father’s flight logbook. He was a pilot in the Marines in the early 1960s, and unfortunately he passed away a year before I was selected as an astronaut. I took his logbook with me, and I recorded my time in space orbiting the world alongside his flights all over the world. My oldest son is now at the University of Michigan and he also wants to fly. I passed that logbook on to him. I’m hoping it will remind him of the grit I learned from his grandfather and that he’ll have an opportunity to record his first flight right next to ours.

On finding lessons in the universe

On finding lessons in the universe

When I gave the commencement address at Illinois in 2014, I emphasized the idea that each and every person has to define their own success. As I said in my speech, if you give that power up and let somebody else decide what you need to be, you will miss out on some fantastic opportunities in your careers and in your lives. I learned that first-hand through my own successes and failures. In the end, it isn’t fame or popularity that determines professional success or personal achievement. We must stand by our own measure.

I gave that talk as much to my kids as I did to the Illinois students graduating that day. I don’t want my kids to feel pressure that they need to be an astronaut because I was an astronaut. My wife and I have always tried to emphasize to them that there are no limits on what they can do. That has been one of my fears, that for some reason they might feel some kind of pressure based on what I’ve been fortunate enough to do. I really hope they get the message that their success and what they do is how they define it, not based on or compared to what I’ve done. I have been fortunate to work at job about which I am passionate. And in that way, I proudly stand beside countless others who have achieved that same dream, and hope to inspire others to do the same.