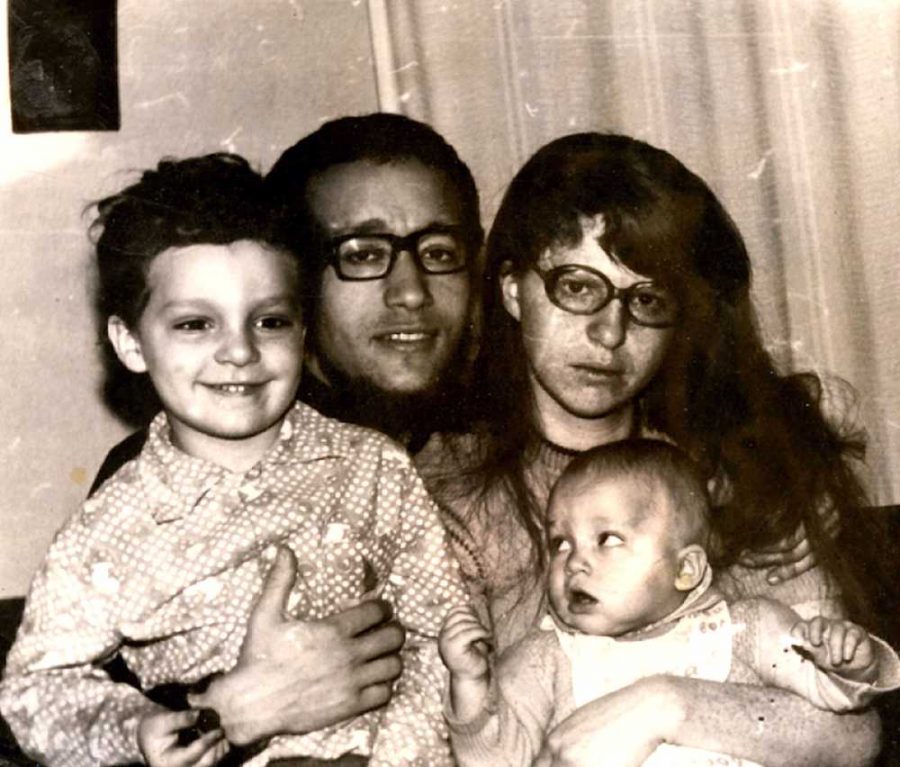

Tucked away in the Holosiivskyi Forest in the early days of the Cold War, Soviet scientists were trying to understand and unlock the code of the universe. Frima Lukatskaya, an astrophysicist, spent her days deep in study at the Kiev Observatory, theorizing about variable and unstable stars.

Two decades after that, in the early 1980s, Frima held her young grandson’s hand as they walked up the hill toward the tall, cylindrical building cast in painted white concrete. The telescope dwarfed him as he sat in the swiveling chair beneath. He listened to his babushka talk about the limitless reach of space.

Frima taught her grandson, Max Levchin, about many things. About stars and strength, about integrity and willpower. She always told him, roughly translated, “Go right through I can’t.”

He’s followed that advice.

✦ ✦ ✦

By any measure, Max Levchin (ENG ’97) has achieved success in Silicon Valley. His companies have become household names, his technology is used by hundreds of millions of people, and he has reimagined the role of technology in consumer finance.

And, by any measure, Max is definitely Frima’s grandson: full of her relentless energy, drive, and focus. Full of the desire to explore and explain something massive—the universe, the internet—and give it shape and meaning.

Max came through Illinois at a time when advances in computing were exploding and the web was becoming accessible to more people. He was part of a group of pioneering Illinois alumni that shaped the modern web—and has never forgotten the lessons Frima taught him or the doors Illinois opened to him. He comes back to campus to talk to students, recruits from our graduates, and, in honor of the woman who taught him so much, supports them through the Frima Lukatskaya Scholarship in Computer Science.

✦ ✦ ✦

From Kiev to Chicago

After the Chernobyl explosion but shortly before the fall of the U.S.S.R in 1991, Max’s family decided to leave Soviet Ukraine. True to form, Frima used her unwavering resolve to orchestrate her family’s complicated exit.

They landed in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago where Max’s mother Elvina continued her career as a software engineer. His father Rafael, an artist, immersed himself in Chicago’s art scene, and Frima, now retired and in remission from breast cancer, remained a force in all their lives.

In Rogers Park, Max would spend many afternoons seated at the kitchen table in his family’s apartment, doing schoolwork with his Mather High School friend Erik Klein. Max and Erik were officers in the high school’s computer club that had just been established in 1993. They would work on Max’s home computer doing what Erik describes as “really, really ancient styles of doing graphics programming.”

In the middle of writing code or dialing-in to pre-internet bulletin boards, Frima would drop two bowls of borscht in front of the boys. Max would tell Erik, “Well, she put it down. We have to eat it.”

Right place, right time

Most 18-year-olds majoring in computer science in the 1990s expected they’d get jobs at IBM, Texas Instruments, or Microsoft after graduation. And the industry expected to welcome Illinois graduates, who were always seen as among the best.

But when Max and his class arrived on campus, a new wave of entrepreneurial spirit was emerging—and it quickly became contagious.

Max arrived in the fall of 1993, a month before the beta release of the web browser, Mosaic. Other more rudimentary graphical browsers had been developed during the same period, but Mosaic proved to be a game-changer. While a student, Marc Andreessen co-developed the browser with a team at Illinois’ National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Andreessen went on to become one of Silicon Valley’s most successful software engineers and investors.

The world took notice. Mosaic would forever change our relationship with computing, especially among the general public who now had a way to navigate the web. Closer to home, Illinois students saw Andreessen’s success through a different lens. If he could build something revolutionary, maybe they could too.

“One thing that really shaped me—and probably a lot of other people at Illinois—was this constant sense of opportunity in the air because of Mosaic and subsequently Netscape,” said Max. “It was this notion that students like us built these amazing tools that were not at all contemplated by the industry.”

It seemed as if anything was possible.

A second home

Max didn’t come to Illinois dreaming of being an entrepreneur. He knew he was passionate about computers, but he expected he’d enter academia just as his parents and grandparents had.

“I walked into U of I with a well-developed point of view that I was going to be just like my grandparents and my parents and get advanced degrees and either research or teach, maybe both. I had no plans to start companies,” he explained. “I grew up in a socialist country, so the notion of starting companies was something that you read about, but you certainly didn’t do.”

Once on campus, it didn’t take Max long to find his niche. He joined the student chapter of ACM, the Association for Computing Machinery, whose office was located in the Digital Computer Lab (DCL) at the time. Max carved a well-worn path with his bicycle between his dorm on Pennsylvania and the ACM office that soon became his second home.

“I can tell you that Eric Johnson’s ‘Ah Via Musicom’ guitar instrumental is exactly how long it is to ride from Blaisdell to DSL on a bicycle at 7 o’clock in the morning. I did that many, many times,” he said. “I seriously contemplated asking my friend if they wanted to rent my bed because I found myself perfectly capable of sleeping in the old SGI lab and then the Spark lab at the old DCL. I can still tell you the prices of various snacks in the downstairs DSL vending machine since that usually constituted my lunch.”

Erik, Max’s friend from Mather High School, was his roommate throughout college. He remembers that each year they were living together Max would spend less time at home and more time in front of computers at labs. Exhausted after a long night of coding, he would burst through the door of their apartment, pour himself a cup of days-old coffee still languishing on the burner, and then he was ready talk.

“We would joke that he was like a scuba diver that would have to come up for air, be able to do laundry and enough to exist, and then go back to work,” said Erik, now an engineering manager at Google.

“I felt extremely at home hanging out with some really cool boys and girls who were not afraid to program computers,” said Max. He laughs as he recalls that he was “probably on the outer limits of nerdy even for the nerds of ACM.”

That fall’s release of Mosaic sent waves through the computing community. Max describes it as a massive shell-shock. “Lots of people, myself included, were trying to figure out what kind of interesting things you could do. My classmates, Luke Nosek and Scott Banister, were constantly discussing entrepreneurial opportunities, and to them the web was a gigantic, green field of endless opportunity. It was a platform that needed to be expanded and pushed to its limits.”

Luke and Scott noticed Max. He was a permanent fixture in the ACM office, so it was hard not to. They were starting a company and asked him to code for them. The three of them started several companies together and all of them failed. Until one didn’t.

✦ ✦ ✦

Work that is hard, valuable, and fun

Over the course of his career, Max has kept a close circle of friends from Illinois, many of whom share his passion for technology and building businesses. This was especially true at PayPal, the breakthrough company that Max co-founded which revolutionized online payments and propelled the growth and accessibility of online shopping.

In its earliest days, nearly all the engineers at PayPal (then known as Confinity) were Illinois alumni. One of those engineers was his best friend Erik, who flew out to California, slept on Max’s floor, and became part of the team.

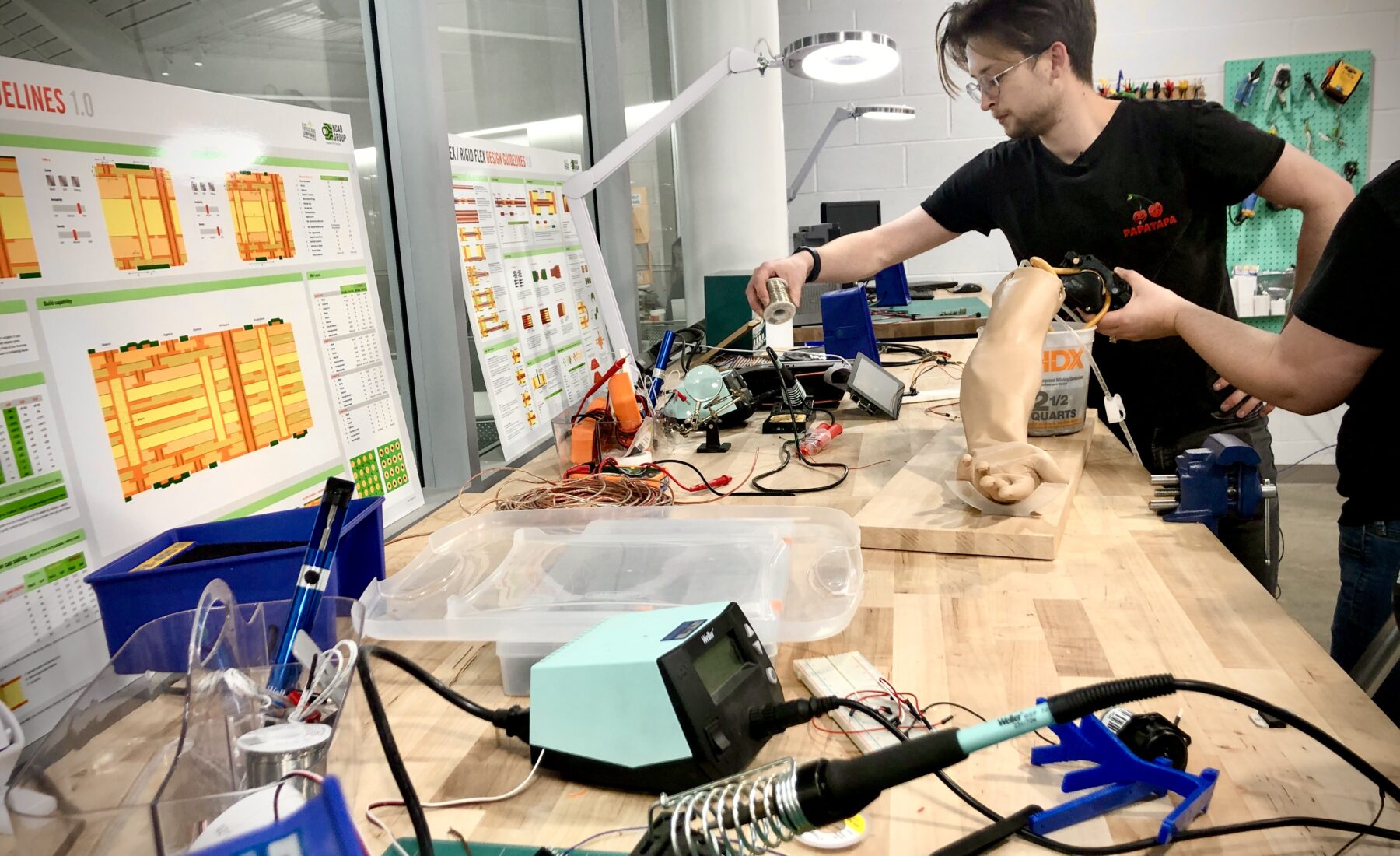

When Max builds a business, he tries to identify ways his innovations can impact the largest possible number of people. In 2011 he started HVF Labs (Hard Valuable Fun), an incubator for building companies that aim to solve hard problems, those that will have a valuable impact on people, and which remain fun to work on. Max’s newest venture, Affirm, grew out of the HVF space and has opened access to people who have been left behind by the credit industry.

“It goes back to where we grew up, a place where it was really hard to make ends meet. The reason I continue to look to Max as a friend and as a leader in Silicon Valley is that he really speaks from his roots,” said Erik. “He thinks of the whole community in the products that he builds. I’m happy he gets this opportunity because of all people, I’d love to see him do more of it.”

“It goes back to where we grew up, a place where it was really hard to make ends meet. The reason I continue to look to Max as a friend and as a leader in Silicon Valley is that he really speaks from his roots,” said Erik. “He thinks of the whole community in the products that he builds. I’m happy he gets this opportunity because of all people, I’d love to see him do more of it.”

Max is in the business of building businesses with integrity.

“In my view, altruism is just the other side of integrity. If you care about the impact of your actions, you end up doing the right thing,” Max said. “If you do the right thing, you do it because you care about the people you will impact.”

This story was published .